Shows

Microwave International Arts Festival – Drifting Lab

Albert Einstein summed up the childlike wonder of artists and scientists in his 1949 essay “The World As I See It.” He wrote: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. So the unknown, the mysterious, is where art and science meet. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.”

Underneath the goliath architecture of the Hong Kong Design Institute (HKDI), Microwave’s humble satellite exhibition, “Drifting Lab” (11/6-21) presented ten prototypes and design concepts by members of the Ishikawa Oku Laboratory at Tokyo’s Graduate School of Information Science and Technology. Compared to the whimsical pseudo-science experiments presented with great fanfare in the main exhibition, “Drifting Lab” remained true to this year’s theme “Alchemy,” as products of a cross-disciplinary relationship between artistic and scientific practices.

At the exhibition’s entrance, a red laser point bounces off the walls of a black and white maze. The playful Laser Sensing Display (2008-), consists of a wall installation and a Smart Laser Projector (SLP) prototype—a type of laser that navigates by measuring surface information such as shape, texture or reflectivity. Developed by Alvaro Cassinelli and Alexis Zerroug, the aesthetic “augmention” of objects on which it projects belies the technology’s practical aspect: SLPs could be used in the medical field to visualize cancerous skin cells, and in industry for detecting surface stress in machinery. Here, however, as an artistic device, SLP adds a dynamic element to the typically static medium of a wall mural.

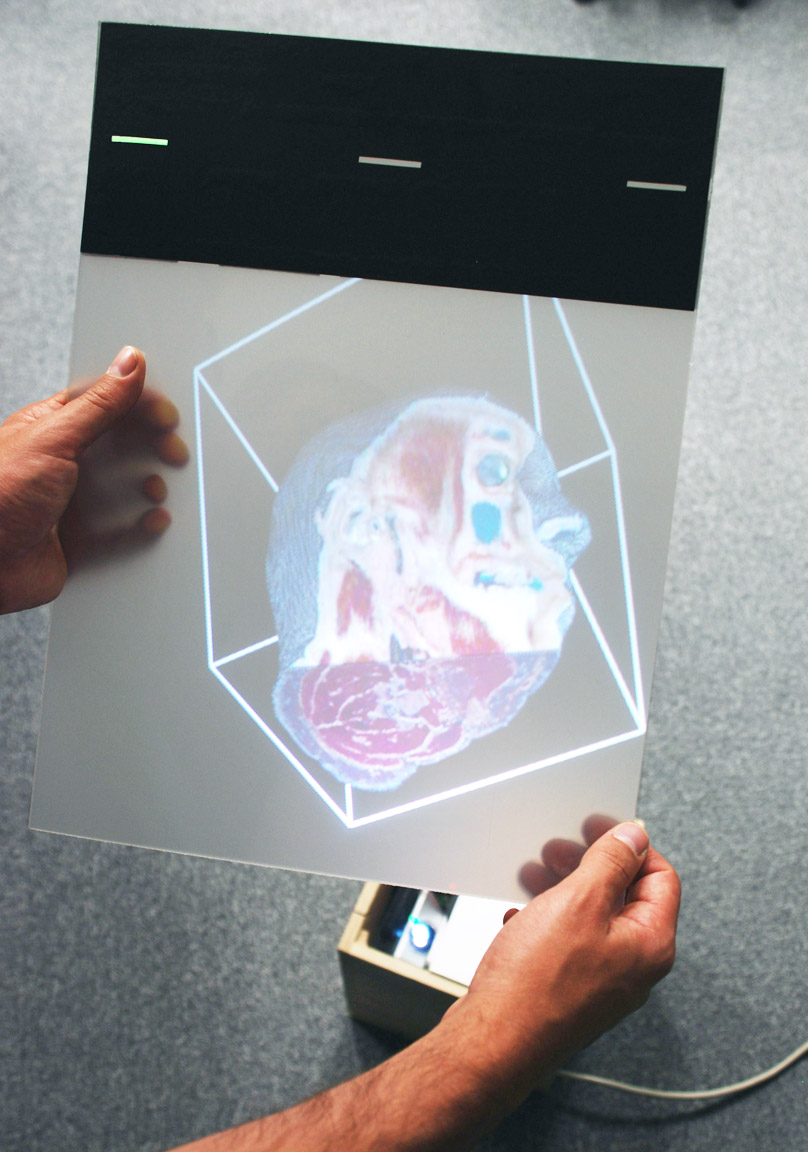

A particularly fascinating work was Cassinelli and Yoshiro Watanabe’s interactive Volume Slicing Display (2006-), in which a 3D image reconstruction of a head is projected onto an untethered, portable tablet of Plexiglas, which acts as both interface and screen. By manipulating the sheet’s angle or distance above a projector, different cross-sections of volumetric data appear on the Plexiglass—as if the sheet were sweeping through a virtual 3D object. The prototype being developed for medical usage could potentially overcome limitations in existing imaging software, which either relies on an enormous amount of calculations to present volumetric data in its entirety, or visualizes only a limited range of cross-sections. However, such a technological breakthrough would no doubt spread to the field of media arts as the information industry pushes toward real-time human-computer interactions.

Created by Tomohiko Hayakawa, Carson Reynolds and Hong Kong-born Eric Siu (currently a resident artist at the Laboratory), with support from Japanese media art unit Maywa Denki, another prototype that tries to bridge the divide of man and machine is Touchy (2011), aimed at overcoming technological alienation by turning a human into an interactive camera. In Touchy, the viewer wears a helmet-mounted camera as a pair of goggles, but cannot see anything. Only when another person physically touches them, setting off a sensor, does the camera take a snapshot giving the wearer a glimpse of the outside world. Siu, a new media artist who is interested in transforming visual experience, plans to show the completed project at Tokyo’s Akihabara district. Partly performance and partly proposed therapeutic process, with this experiment Siu hopes to socially engage the gamers and computer geeks who flock to the city’s “Electric Town.”

Amidst the high level of specialist expertise in contemporary society, it is easy to forget the historical relationship between art and science. Art fans tend to overlook times at which the two have been inseparable: the relationship between mathematics and aesthetics, for example, has been appreciated at least since the Ancient Greek discovery of the golden mean. Industrious curiosity has led to creative inventions in what we would now divide as arts and sciences, yet have often been by the same individuals. A little-known example is the 19th century French physician René Laénnec, a poet and a flute player, who invented the stethoscope based on his knowledge of acoustics. In the 20th century, trans-humanist art experiments developed into the avant-garde, kinetic and new media art of today. “Drifting Lab” embraces the shared sense of awe that allows a two-way discourse between art and science, where we find both technological innovation inspired by playful creativity and practical inventions appropriated for artistic expression.