People

Life as Performance Art: Tehching Hsieh at Carriageworks

Tehching Hsieh is 63 years old and quite elf-like, with a small, lean and muscular frame. Even though he has lived in New York for 40 years he speaks English with a thick Taiwanese accent. He arrived in America in 1974 when, as a seaman, he jumped ship at a port on the Delaware River. For 14 years he lived as an illegal immigrant, calling himself Sam Hsieh, before being granted amnesty in 1988. By then he had virtually finished his career as a performance artist but for one piece, Thirteen Year Plan (1986–99), for which he made art that he was determined not to show to others.

He has five earlier works—all monumental, yearlong endurance pieces made during the late 1970s to mid-1980s—which share a conceptual similarity in that, according to Hsieh, they are philosophical investigations into the nature of time, life and being. In them, he locked himself in a cage in his New York studio loft without access to television, radio or conversation (Cage Piece, 1978–79), lived on the streets of New York (Outdoor Piece, 1981–82), was tied to another artist by a three-meter-long rope (Rope Piece, 1983–84) and spent one year neither thinking about nor practicing art (No Art Piece, 1985–86). And it is the one other work from this series, entitled One Year Performance 1980–1981 (Time Clock Piece) (1980–81), that is the subject of an exhibition taking place at Sydney’s Carriageworks art space, where he also recently talked to ArtAsiaPacific.

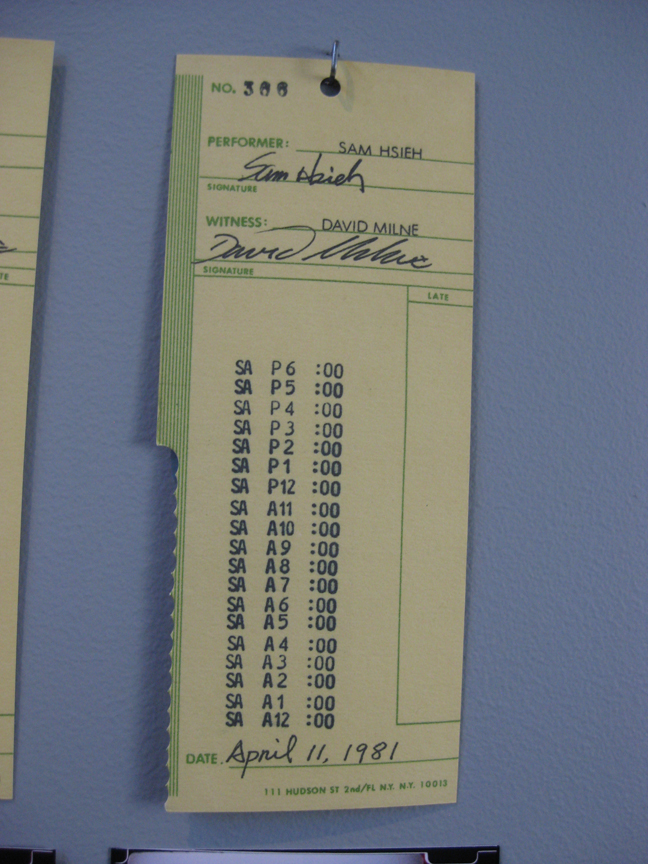

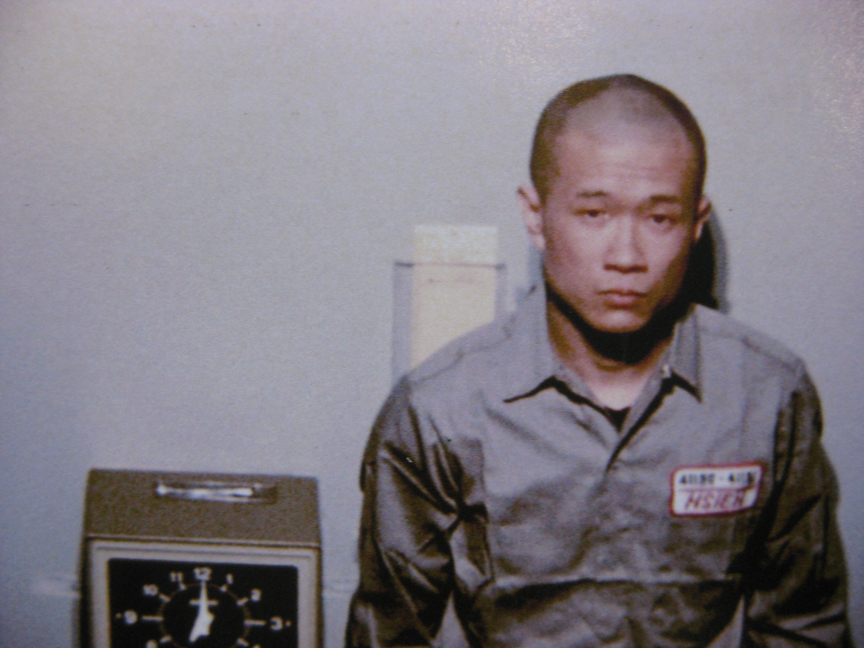

In the original Time Clock Piece performance, Hsieh, dressed as a factory worker, pushed a yellow card into a time clock (installed in his studio) to register the time and date on the document, every hour on the hour for the duration of one year. Each time, he also took a photograph of himself standing beside the machine. “The time clock was in an adjacent room [from his main studio], so I had the sense that I was going to work. For one year it became my work,” he said.

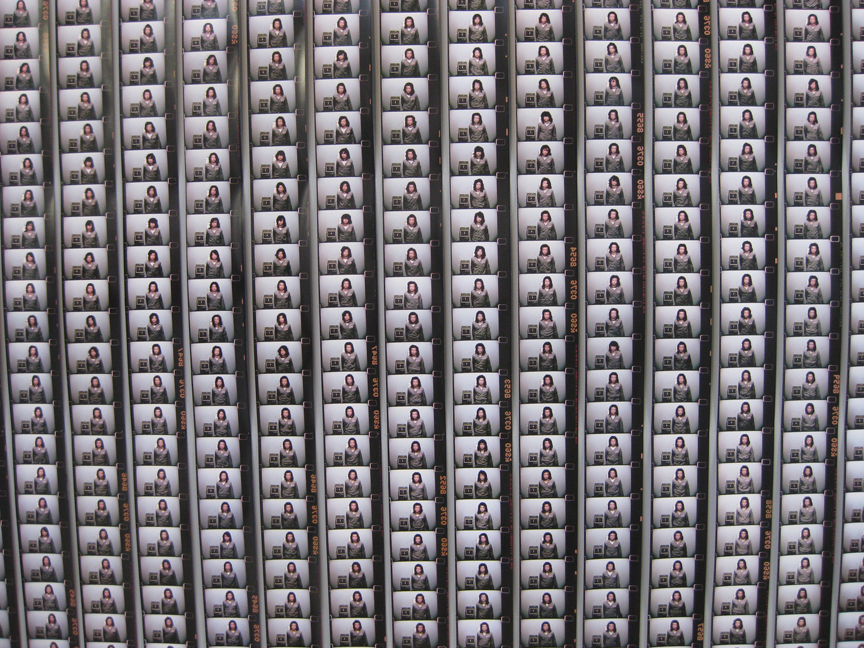

Hsieh repeated this action 8,760 times during the year, a period which began when a witness signed all 366 time cards in order to ensure that they couldn’t be replaced with premade ones. The 8,760 accompanying photographs, as well as letters, posters and calendars that were relevant to the performance, were condensed into a six-minute film—now exhibited at Carriagworks—in which we can also see Hsieh’s shaved head gradually become covered with unruly, grown-out hair.

During the year of this performance, he was not able to sleep for more than an hour at a time for fear of missing the alarm; though there were occasions, 133 times to be precise, when he did fail to “clock in.” Once, it was simply because someone in the building had pulled the plug on the electricity supply; other times he had innocently slept through the alarm. But such failure is part of the “infallibility of the human process and an integral part of the work,” according to Hsieh.

While going through all of these endurance pieces, Hsieh systematically applied his mind to try to understand the nature of time—an investigation aided by earlier readings of Dostoyevsky, Kafka and the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who forever pushes a boulder up a hill only for it to roll back down when he reaches the top.

There is more than a whiff of nihilism and insanity to it all. While the labyrinthine exploration would have had a lesser artist reeling, Hsieh was determined to collapse the intellectual distinction between the nature of time and that of art, and explore whether the two are mutually exclusive.

Though Hsieh may not have arrived at a totally satisfactory answer to this conundrum, he has certainly developed a cogent argument for the democratization of art—that is, if one accepts his proposition that art can simply comprise of doing nothing. This was a position he arrived at prior to his embarking on Thirteen Year Plan, which witnessed a shift from “working hard to waste time”—the central focus of Hsieh’s yearlong pieces—to one of simply wasting time as an art form in itself.

Hsieh’s performance pieces, neglected in their early days, have recently been rediscovered by a contemporary crowd riddled with existential angst and whose consumption of art is predicated on the instantaneous “here and now” propagated by the internet. Hsieh’s endurance pieces almost defy logic, but, none the less, beguile viewers through their lofty commitment to a personal endeavor that few of us would ever want to replicate. Hsieh’s current popularity has also been aided by an extensive monograph published in 2008 and exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Guggenheim Museum in 2009.

For Hsieh, wasting time is a way of dealing with life’s absurdities. “Everybody wastes time, but for me it is my work. My work is about passing time. Doing art is doing time. Doing life is doing time. So I came to Sydney to waste my time, but I feel good [about it],” he said.

Hsieh stopped making art in 2000 when the 13-year period of his Thirteen Year Plan drew to a close. But since then, far from simply wasting time, he now spends his days wisely promulgating his new-found popularity through talks and exhibitions of the archival documents and "detritus" that resulted from his performances.

“Tehching Hsieh: One Year Performance 1980–1981” continues at Carriageworks, Sydney, until July 6, 2014.