People

The Essential Works of Bharti Kher

From anthropomorphic goddesses to dizzying bindi patterns, Bharti Kher’s creations are an ode to the symbiotic contradictions in our world. Whether a painting, sculpture, or installation, each of her artworks combines disparate elements that collide and transform in unexpected ways, much like the British Indian artist’s own hybrid identity.

Born in 1969 in London, Kher is the daughter of Punjabi immigrants who worked hard to secure their livelihood in Surrey’s bourgeois suburbs. Although she grew up hardly speaking her mother tongue and only visited India once as a child, she was always drawn to Hindu mythology, traces of which can be found throughout her animalistic creations. What Kher is best known for, however, is her recurrent use of the bindi (from the Sanskrit word bindu for “dot,” “point,” or “drop”), a colored dot of paint or sticker that South Asian women traditionally wear on their foreheads. The singular dot is laden with social and religious codes most commonly related to marital status and the ajna chakra, the all-seeing third eye that connects the consciousness to the spiritual realm.

Kher began painting with bindis in 1995 after seeing one on a woman’s forehead at an Indian marketplace. In her twenties, Kher had set off for India to explore her heritage, eventually relocating to New Delhi to be with her husband and fellow artist, Subodh Gupta. The remigration to the subcontinent influenced her artistic practice, reflecting the cultural estrangement she experienced as a second-generation immigrant returning to an unfamiliar homeland. To make sense of these contradictions, Kher began to fuse clashing elements of British and Indian life, tradition versus modernity, as well as incorporating tropes from various genders and species. Throughout she never offers a solution—for her, the role of art “is not to answer, but to ask.”

In a career spanning three decades, Kher has exhibited her art internationally, with solo shows at venues around the globe, from the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai (2014) to her long-time gallery Nature Morte in New Delhi (most recently, in 2021), and Arnolfini in Bristol (2022). In 2022, the London-based private foundation Parasol Unit presented her work in a group exhibition “Uncombed, Unforeseen, Unconstrained” at the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale. She is also the recipient of various accolades, from the prestigious Sanskriti Award (2003) and being named YFLO (Young Ficci Ladies Organization) Delhi Woman Achiever of the Year (2007) to Denmark’s ARKEN Art Prize (2010), and France’s highest cultural award, l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (2015).

Currently, Kher is holding her most extensive exhibition in the UK to date, titled “Alchemies,” at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in West Yorkshire. The exhibition, which opened in June, revolves around womanhood and mythology, featuring works that she made over the last 20 years, including four outdoor bronze sculptures. To commemorate this major survey, here is a look at Kher’s most iconic works.

The Hybrid series (2004)

On the question of identity, Kher is not at all interested in clear-cut answers. Instead, she prefers to dismantle the notion of an easily defined self, rejecting cultural and aesthetic limitations, as “parts of us are essentially savage, animalistic, and primal.” This adage underlines her aptly named Hybrid series (all 2004), which includes five digitally collaged photographs of women whose bodies are mutated into half-animal, half-human creatures. In The hunter and the prophet, a puma-faced lady holds a feather duster in one hand while stepping her flaming red knee-high boots onto an animal carcass. In Feather duster the same figure reappears, this time with a chimpanzee head, peering ominously from behind meat suspended from a hook in front of her. Meanwhile, Angel and Family portrait each show a pregnant mother alongside her interspecies children and a magenta vacuum cleaner, its nozzle resembling the head of a dog. The grotesque female bodies are positioned in the domestic roles of cooking, cleaning, and raising children; while they comply with these gendered acts to a certain extent, their imperious forms exude power and even self-indulgence, as they choose to embrace and savor the multiplicity of womanhood.

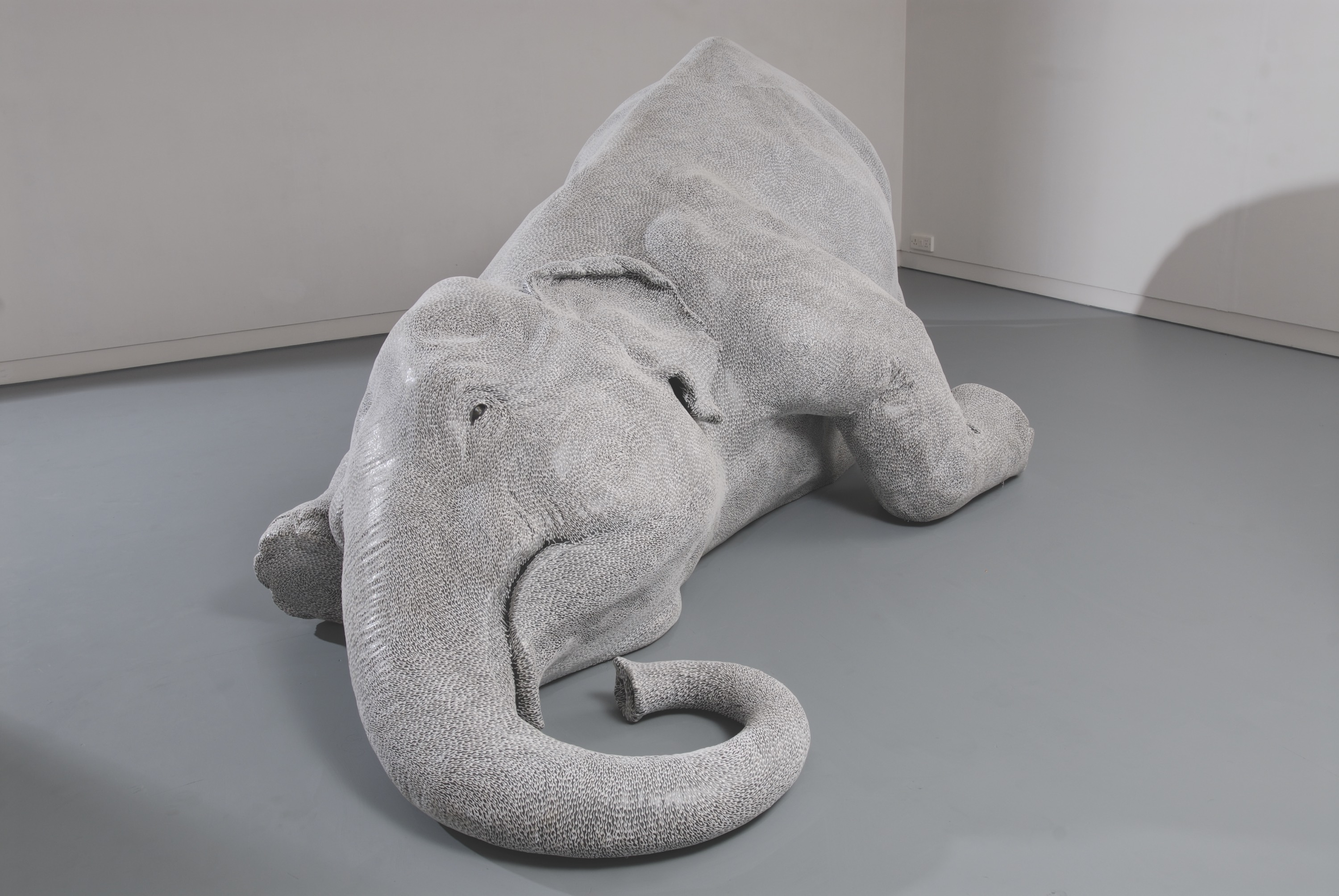

The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own (2006)

The life-sized elephant sculpture, titled The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own (2006), is arguably Kher’s most famous work. It fetched USD 1.5 million at a Sotheby’s London auction in 2010, breaking the record for the most expensive auction sale by a contemporary artist from India. Made of fiberglass, the female elephant is covered in thousands of white sperm-shaped bindis—a process that took Kher ten months to complete. In contrast with the bindis’ dynamism, the animal is slumped down on the floor, suspended between life and death. Further dualities are at play as the elephant is a sacred animal in Hindu scriptures and temples, most notably personified by Ganesha, the elephant-headed god of beginnings, wisdom, and prosperity. Following the subcontinent’s economic boom, however, the revered elephant has become an endangered species, pointing to the destructive impact of globalization and commerce, which have also diminished the bindi to a mass-produced fashion accessory.

Arione (2004) & Arione’s Sister (2006)

Kher’s explorations of gender and species are epitomized by the freakishly alluring figures of Arione (2004) and Arione’s Sister (2006). At nearly two meters tall, Arione is an imposing fiberglass sculpture of a dark-skinned, bare-chested woman in hotpants holding a tray with cherry-topped muffins. A pink heel graces one foot, while the other is a horse leg complete with a hoof; a closer look at her head reveals a buzzcut made of black sperm-shaped bindis. Though her state of undress might seem degrading, Arione is far from subservient as she gazes ahead boldly, one hand on her hip in a combative stance. Two years after Arione, Kher created Arione’s Sister, an alien-like woman with greenish skin and white shapes protruding from her bald head. Wearing only a short skirt, her naked torso is covered in a whorl of multicolored bindis. One pale, equine leg is lifted mid-step, while the other foot wears the same pink stiletto as her sister. Shopping bags pile up on her arms, fanning around her like an aureole, a religious motif usually connected to holy figures. Although the bags are heavy—signifying the social pressures that literally and figuratively weigh her down—Kher underpins their celestial connotation: “[T]hey’re wings and she’s going to fly.”

Both sisters exhibit the patriarchal standards that condition women to consumerism and servile domesticity, but their polymorphous forms resist these constraints, reclaiming feminine power and liberation. Paradoxically, Arione (derived from the eponymous steed in Greek mythology) and her sister challenge these dehumanizing ideals through their animal hybridity. Embedded in this work is Kher’s idea of the self as multiple, and that embracing contradictions is not only natural, but essential to understanding and freeing ourselves.

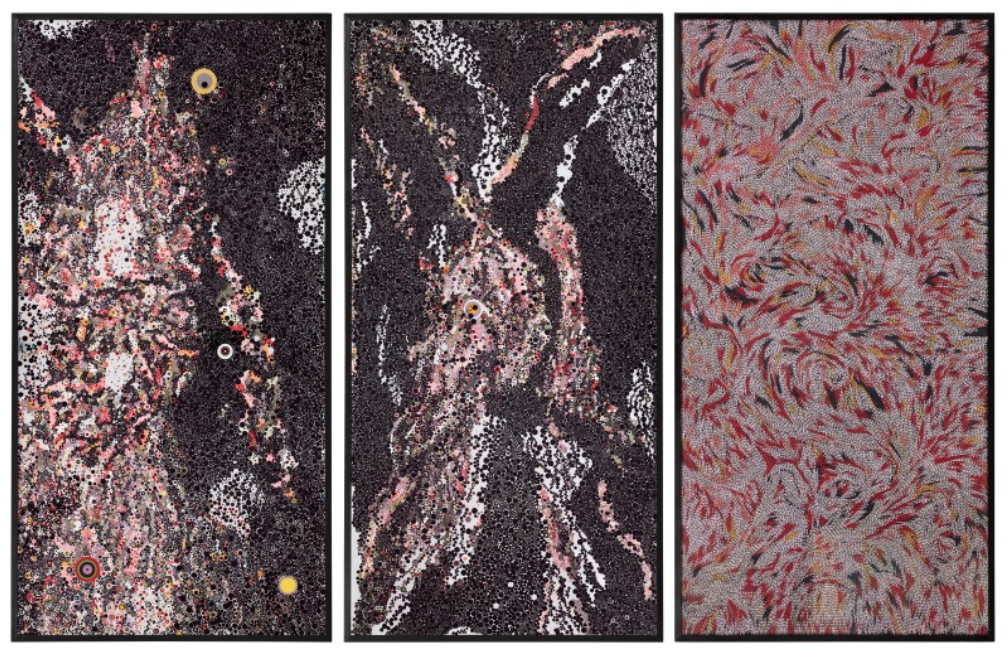

Itch, Scratch, Raw (2006)

Itch, Scratch, Raw (2006) is an enormous triptych with thousands of felt bindis swirling across each reflective aluminum panel. From far away, the sinuous patterns resemble microscopic cell clusters or satellite images; they first appear relatively unconnected before converging into a heterogeneous mass, echoing human migratory patterns in a globalized world. There is an undertow of violence and disorganization, as the artwork title suggests, alluding to the Western colonial project that continues to ravage life in the Global South, which in turn fuels migration. Kher doesn’t embellish her sociopolitical critique, but her bindis are above all a symbol of transfiguration, representing cultural interplay amid the torrent—a glimmer of hope, and of healing a wound, scratched open and raw.

Untitled (2008)

Untitled (2008) is a burst of colorful, multisized bindis layered on top of each other on a painted board. From bright pink to black, the flashy hues reflect the burgeoning “New India” that Kher experienced after her relocation to New Delhi following the completion of her studies in Newcastle, England. The bindis proliferate into abstract clusters, signifying the explosive growth of the Indian economy brought about by economic reforms in the 1990s. As the country regained its geopolitical prominence, the Indian art scene, which at the time was, according to Kher, “very small” but also “fresh and exciting,” opened itself to influences from around the world. Here, she renders the bindis in an op art style, denoting a vibrant and gainful exchange between cultures—though this did not happen without repercussions. As Western values and trade gained footing, traditional items like the bindi became a commodity far removed from their original meaning, reflecting an India both propelled and eroded by globalizing forces.

An Absence of Assignable Cause (2007)

Unable to find photographic evidence of the blue whale’s heart, Kher embarked on “a hunt for a chimera” which led to her creating An Absence of Assignable Cause (2007), a life-sized, imaginative visualization of the elusive organ. Dark turquoise, green, and red bindis engulf the two-chambered heart, adorned with protruding veins and arteries. With only rough sketches to reference, Kher designed the sculpture mostly from imagination, fusing reality and fantasy, as well as the physical and emotional. Like her other bindi-flecked specimens, the whale heart is a metaphor for the human condition and our everlasting struggle to understand its mysteries of life, love, and death. Furthermore, the environmental message is clear: though it seems to pulsate with life, the extracorporeal heart also warns of extinction, whether through human destruction or apathy.

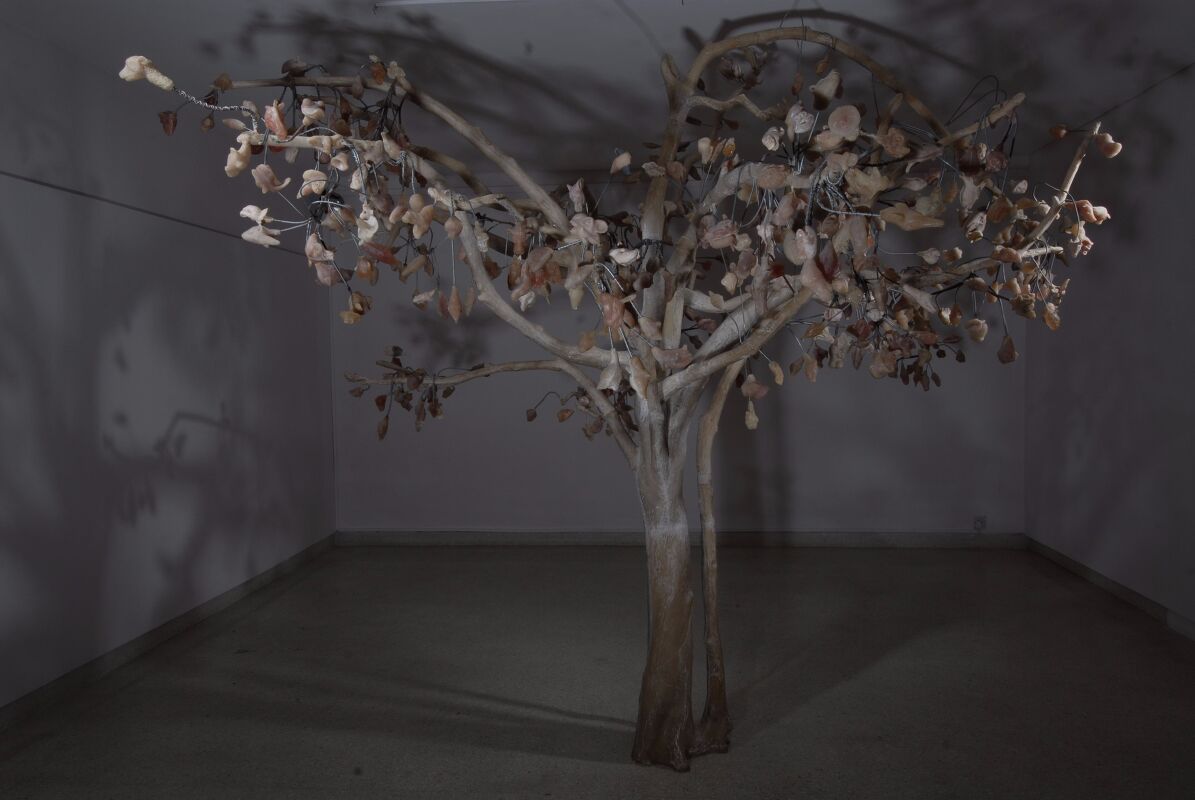

Solarum series (2007)

At about three meters in height, Solarum (2007) is a giant fiberglass tree, its branches teeming with hundreds of golden fruits—except a closer look reveals them to be miniature animal heads made of a light brownish-pink wax. The fruits' fleshy color gives off a “human feeling,” says the artist, reflecting at once our connection to the natural world as well as our growing alienation from it. Beyond its eerie naturalism, Solarum draws upon the tale of Alexander the Great who, on his march to India, encountered a talking tree that prophesied his death. Disturbed by this premonition, Alexander repeatedly asked the tree about his fate in the hopes of getting a different answer, but to no avail: his great conquests, and his life, would inevitably come to an end. Infused with this mystical legend, Kher’s tree is as enchanting as it is ominous, a warning against Western colonial hubris, but also a reminder of human mortality and the uncertainties of life beyond our control.

The Deaf Room (2001–12)

For The Deaf Room (2001–12), Kher melted ten tons of red glass bangles into cuboids, stacking them into a chamber-like structure. Dark and glossy, the translucent bricks emit a soft glow when set against a backlight. Despite its geometric simplicity, the work is a haunting reminder of the 2002 Gujarat religious riots, which led to over 1,000 deaths and widespread sexual violence. The glass bangles, a traditional piece of jewelry worn by Indian women, would usually jingle against each other in a delicate melody—in their inky, solidified form, however, they now exude the oppressive silence of a tomb. In Kher’s words, there is “a sense in the work that women somehow pay a price, and that’s absence.” Charged with female energy, The Deaf Room gives voice to women who have suffered horrific cruelty and subsequently been stifled, remolding and preserving their memory in a grievous yet meditative monument.

Six Women (2012–14)

Six Women (2012–14) comprises life-sized plaster casts of six naked women seated next to each other on wooden panels. Their hair is neatly tied into buns, and their eyes are closed, expressions solemn. Void of Kher’s usual polychromatic touch, the all-white plaster makes the women seem ethereal. The casts are based on the bodies of aged sex workers from Kolkata whom Kher paid to pose in her studio—a transaction that unsettled her: “What then makes me different from the client . . . in this and most cases the man? Does my empathy . . . [and] work as an artist give validity to the role I play in the circus of meaning?” Embracing her discomfort, she focused on baring the women’s complexities, which are effaced by their profession and the patriarchal beauty standards at large. Even as their perceived flaws are on full display, Kher presents them with a tenderness not often granted to older women: soft belly rolls, delicate wrinkles, and weary yet graceful shoulders. Casting their bodies was in itself a visceral process, as Kher tried to “capture their breath, to find the imprint of their minds and thoughts, and the secrets of the soul.” Though austere, Six Women is an emotive and complex work, challenging our perception of marginalized women and contemporary body politics.

The Intermediary Family (2018)

Towering almost five meters in height, The Intermediary Family (2018) is Kher’s largest work to date. It is based on an assortment of small clay objects from South India, called golu, which are usually displayed in religious festivals. To Kher, they “represent an entire range and source of life—from animals to gods to the secular.” The year-long creation began with breaking the clay figures apart, melding them into variable shapes, then forming the final configuration into a bronze sculpture. Different angles reveal the hollows in each body, unveiling their hidden vulnerabilities and inviting us to “look inside, as opposed to the outside.” In a process of fragmentation and repair, The Intermediary Family represents the chaos of human psychology, as well as generational family connections, as Kher likens the sculpture to the portrait of a mother, father, and daughter. In this sense, the figures transcend not only their objecthood but also time: the worn bronze recalls an old, discolored heirloom, passed down through generations, and heavy with memory.

Animus Mundi (2018)

Reminiscent of the Venus de Milo, Animus Mundi (2018) is a large sculpture of a nude goddess draped in a blood-colored sari—one end of the lacquered cloth spills out of her mouth. Her head is that of a cow with mighty horns: a sacred animal in Indian culture. Kher’s bindis sprawl across its hide, as well as the woman’s torso and under-eye area. The figure is both familiar and strange, referencing the ancient Greek marble statue while the sari coated in resin, giving it a crumpled and rigid texture, is suggestive of old customs that remain anchored in the past. But beyond questions of tradition and modernity, Kher says this sculpture represents the universal “connection between all living things, the vital force in a world that carries all human and animal energies.” Drawing from the Greek philosopher Plato’s concept of the anima mundi, or the “world soul,” which posits the world as a living, spiritual organism, Kher emphasizes that the human experience is profoundly complex and invariably connected across all borders of time and space. Though her biography shines through in this work, it is all-encompassing—or, as Kher has aphoristically said about her sculptures: “[T]hey are you.”

Annette Meier is an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.

Bharti Kher’s solo exhibition “Alchemies” is on view at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park until April 27, 2025.