Shows

Xu Zhen’s “Alien”

Xu Zhen’s solo exhibition, “Alien,” presented at ShanghArt in Shanghai, was split over two floors. The first level featured a site-specific, large-scale installation titled Alien 1 (2017–18), while recent paintings and sculptures, ostensibly connected to the installation, were displayed on the gallery’s upper floor.

Upon entering, visitors were confronted by a prison-like environment. Multiple stone figures were kneeling in dirt, clad in an orange that brings to mind jail uniforms, some hooded, some wearing earmuffs and blackout goggles. The work, Alien 1, refers to the human rights violations committed by the United States within the walls of Guantanamo Bay as well as Abu Ghraib prison in the name of the “war on terror.” By way of such a reference, the artist attempts to address the contemporary politics of conflict, protest, migration, and the identification of “alien” combatants.

The exhibition’s accompanying text describes Xu’s growing interest in the social realm and the issues of globalization, such as “trade and capital, conflict and war, evolution and variation.” Yet, the installation, so heavily rooted in the much-discussed horrors of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay, leaves the viewer with the impression that Xu is arriving too late to a specific conversation, rather than commenting on the wider implications of migrants, detention, and border porousness. Further, Xu’s use of figures based on Han-dynasty sculptures of servants as stand-ins for prisoners—which creates a false equivalence between servant and political prisoner—suggests a troubling understanding of the power dynamics at play in international politics. After all, the Han are the dominant ethnic culture in China, with their own colonial and expansionist history—a far cry from the victims of abuse caught up in Pax Americana, for example.

The very familiarity of the violence that unfolds in prisons, delivered via sensationalized images, removes much of the visual power of Alien 1. Indeed, one feels that Xu’s contribution is not only ill-timed, but a cynical, commercial tie-in that capitalizes on migrant-related discussions, much like a product from his MadeIn Company, designed for institutional consumption (the show was presented under XU ZHEN®, MadeIn's "flagship art brand").

Moving to the second floor, the center of the space was dominated by Alien 2 – Sleeping Hermaphroditos, Western Han Dynasty Female Musician Playing a Zither (2017–18), with another figure dressed in orange, Han-style robes. This sculpture, however, kneels over a hermaphrodite figure from Greek antiquity, such that the Chinese figure appears to be giving a massage, beckoning associations with certain Orientalist paintings, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Bath (1885), set in a Turkish hammam, with images of white bodies luxuriating in the caresses of colored servants for the titillation of European collectors. It is interesting to note, too, that the Orientalist period, itself a product of occupation, reimagined the bathhouse as a brothel. In this context, the image of a Chinese figure massaging a white body feels especially problematic.

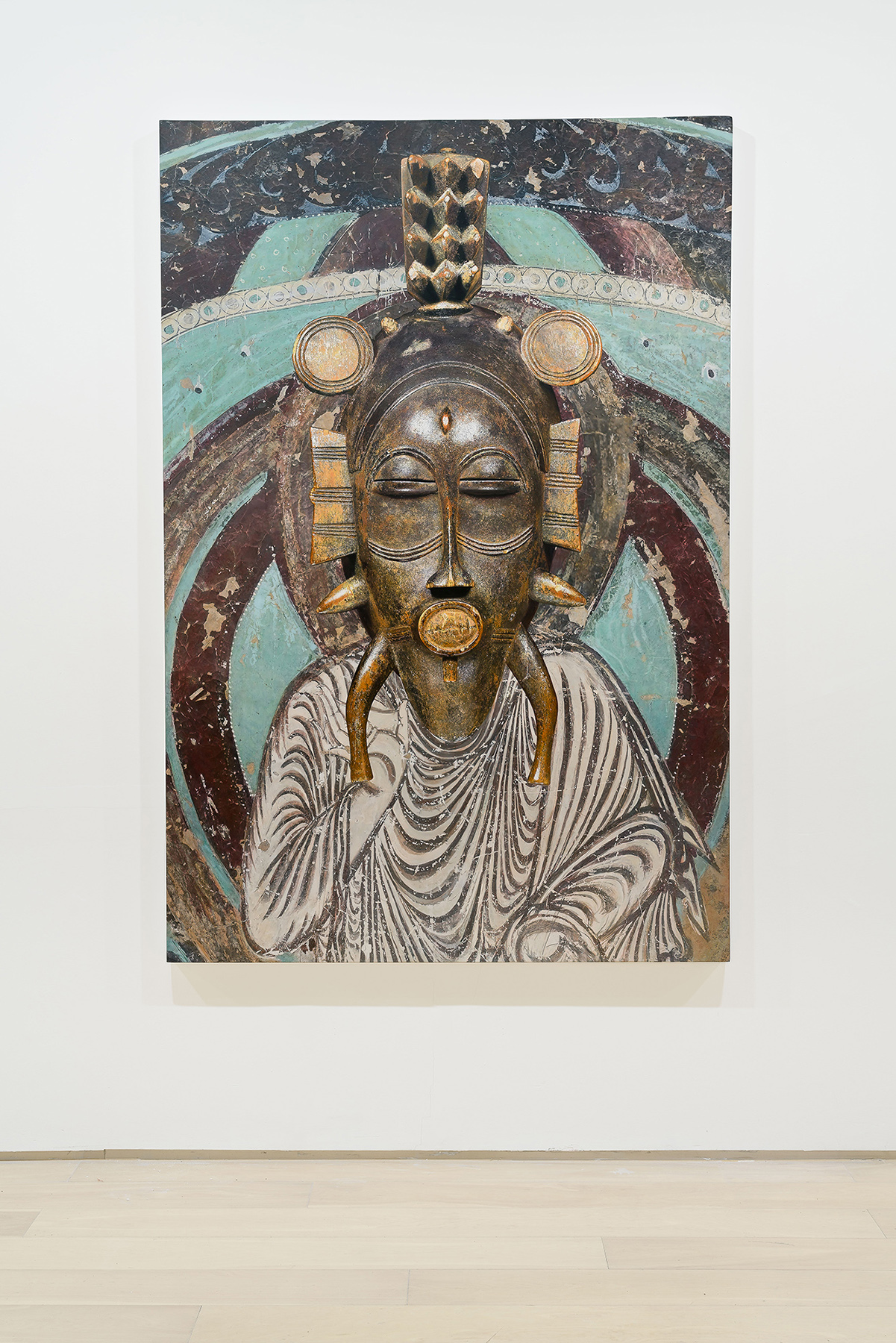

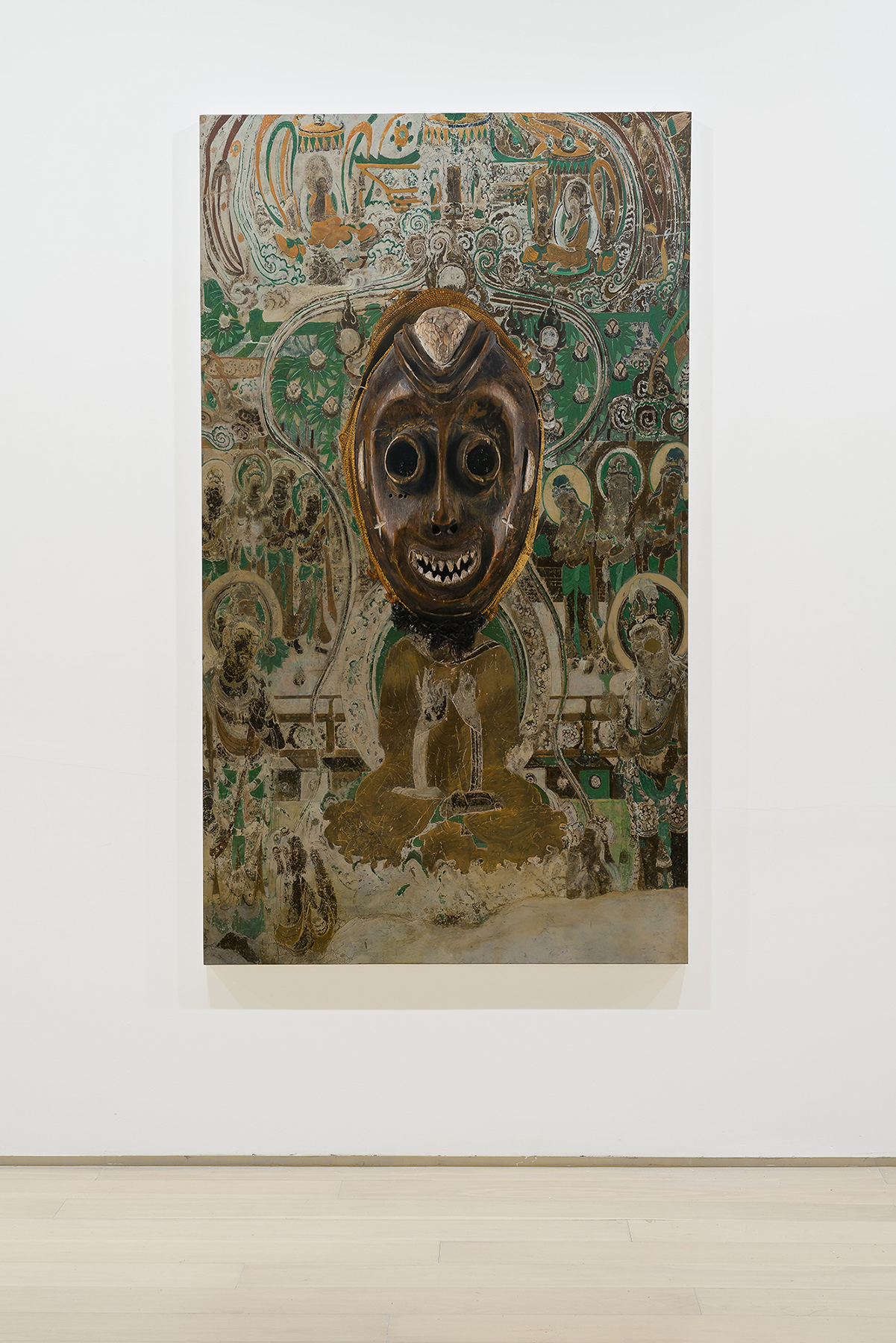

Surrounding Alien 2 were prints, which feature the bodies of Buddhas collaged with appropriated images of African masks—a juxtaposition that Xu has utilized since 2007. The two elements perhaps hold relevance in the contemporary context of Chinese “dollar diplomacy” with African nations, where Chinese economic support is seen as being traded for diplomatic recognition, especially with regards to China’s claims over Taiwan. However, the appropriation of the images is complicated by the artist's voiced desire of achieving a “harmonious blending across time,” discounting any political intent on his behalf. This superficial engagement with the icons of different cultures is reinforced by Xu’s use of terms like “primitive” to describe his African source material.

Xu himself rejects a political intent in his work, saying that he is simply working with visual material, which is a common claim from Chinese artists looking to avoid censorship on the mainland, though it is impossible to ignore a political reading when presented with installations such as Alien 1. Instead, Xu puts the emphasis on the viewer. At the press preview of the exhibition, he explained as much: if you read the works politically, that is your interpretation. This creates the impression of an artist who wants to have a foot in two camps: providing social and political commentary while putting the responsibility for such an understanding of the work squarely elsewhere. As such, Xu loses the credibility of, say, Ai Wei Wei, with his overt political rhetoric. One is left disbelieving Xu’s intent and, at the same time, having little to admire on a purely aesthetic level.

Xu Zhen’s “Alien” is on view at ShanghArt Gallery, Shanghai, until July 26, 2018.