Shows

“Voice of the Thunder Dragon”

A group exhibition on Bhutanese contemporary art reaches the United States for the first time at a pop-up show along the Bowery in New York City. At a time when Bhutan looks to entice more tourists to its Himalayan kingdom, “Voice of the Thunder Dragon” dares to ask questions about the effects of a traditionally Buddhist country opening up to the influences of globalization. The works by Kama “Asha Kama” Wangdi, Pema “Tintin” Tshering, Phurba Namgay and Gyempo Wangchuk, all of whom previously trained in folk and religious art practices, exemplify how a growing handful of Bhutanese artists strive to break the mold.

“Bhutan is such small place,” said Tshering, the only artist out of the four able to make the trek abroad for the show’s opening. “We are only a few, maybe 20-30 artists. It’s a tough thing being an artist there.”

Perhaps no other institution has been as fundamental to nurturing young talent as the Voluntary Artists’ Studio, Thimphu (VAST), which was co-founded in 1998 by Tshering’s mentor, Asha Kama. “So almost all of contemporary art, in some sense, flows through Asha Kama,” said curator Maxwell S. Joseph, who is concurrently working on a documentary, entitled Where the Wind Blows, which explores similar themes seen in the exhibition and is set to debut in June.

Layering gold paint atop bold, earthy colors, Wangdi deconstructs Buddhist iconography in his “Presence Series” (2016–17). For three of his pieces, he saved scriptural parchment that was intended to be burned and repurposed them, thus giving a “second life” to religious art. While techniques of Bhutanese craftwork have been handed down over thousands of years, often resulting in uniform methods of implementation, Wangdi has cultivated an idiosyncratic approach to his work. Indeed, his ability to balance tradition with self-expression solidifies his position as the progenitor of Bhutanese contemporary art.

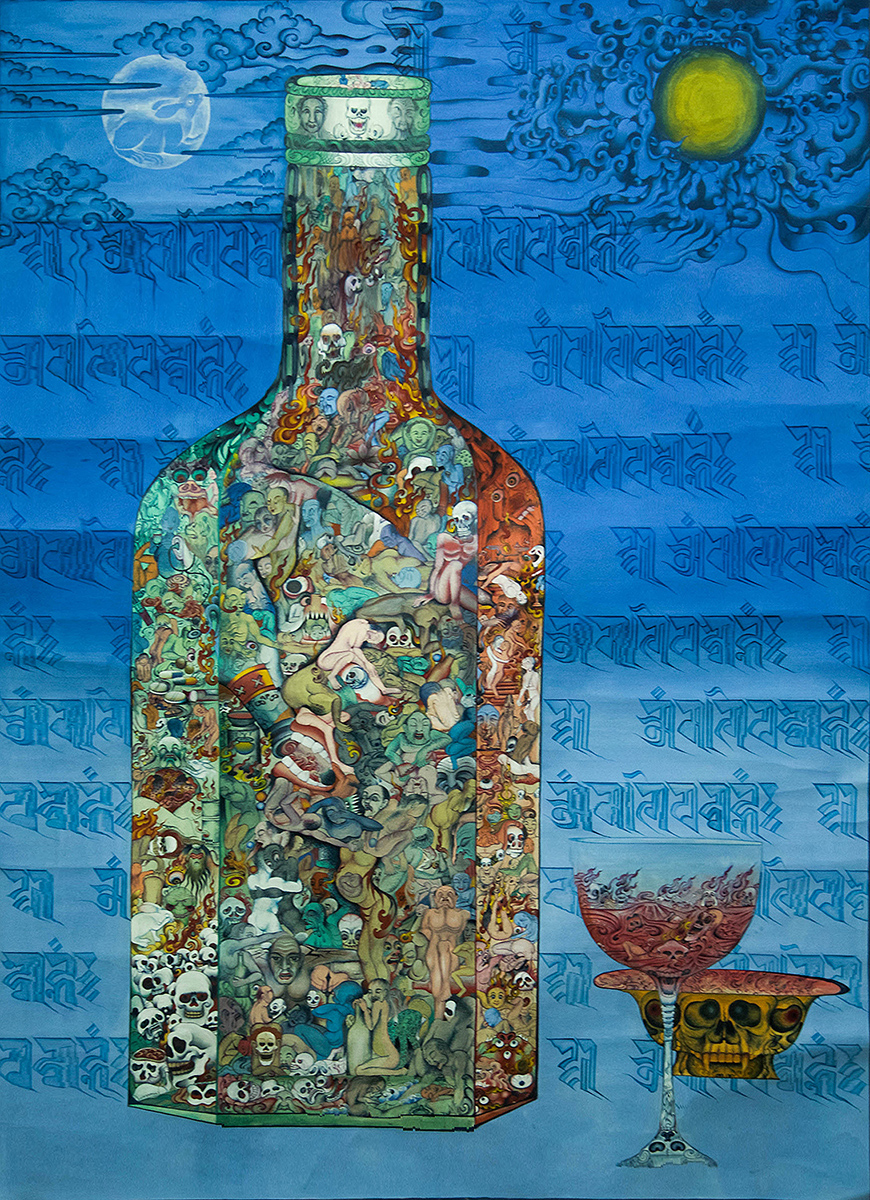

In Spirit of Suffering (2014), Wangchuk reinterprets traditional aesthetics and themes to explore a personal struggle, specifically the loss he suffered as a result of his late father’s alcoholism. Three panels make up the whole of the bottle: on the left, a rendering of his father’s addiction and eventual death from liver failure; in the middle, the many social ills caused by alcohol abuse, ranging from acts of lust to psychological effects to fetal alcohol syndrome; on the right, an allegorical tale about the consequences of drinking. Although Bhutan is known for high gross national happiness, as with any society, it is not without darkness.

Another piece that may upend the West’s preconceptions about Eastern cultures is Wanghuck’s Lives of the Phalluses (2016), which pays homage to the prolific symbol, whose roots in Bhutanese painting can be traced back to a 15th-century monk who wanted to push back against the “prudishness” of Buddhism.

Furthering this tension between Old World and New World, Tshering’s work refashions three Buddhist archetypes—the deity, the monk, and the warrior. By painting deities with guns and rifles in the series “Protectors of Dharma” (2015), he contemplates the nature of their power in a modern context. In “Spiritual Being 1” and “Spiritual Being 2” (both 2015), in which monks pose with gang signs while gang members pose with mudras (the symbolic hand gestures normally depicted on images of Buddha), he inverts masculine aggression with the struggle to attain enlightenment. Tshering additionally works in a variety of mediums, including film, animation, design, and sculpture; his interest in comics is particularly evident in the graphic elements and pop of bright colors that characterize the portraits.

Because Bhutan’s culture has remained untouched for so long, with deep-seated artistic traditions, the contemporary artist faces both a challenge and a burden to educate, according to Tshering. Just as Wangdi formerly taught him, he has already begun to act as teacher to a new generation of aspiring creatives. In this way, he hopes that the contemporary art scene will continue to evolve and attract more attention. “Everything you do becomes a new thing,” said Tshering. “You can’t hope that every piece of work will be understood by the general Bhutanese people. So it’s a struggle, like every beginning.”

“Voice of the Thunder Dragon” is currently on view at 263 Bowery, New York, until February 28, 2017.