Shows

The Imaginary Order

Away from the international galleries in the financial city center, Gallery Exit is tucked away in the modest neighborhood of Hong Kong’s oldest fishing port, Tin Wan. Among other smaller galleries that challenge the status quo of Hong Kong’s cash-rich art scene, Gallery Exit certainly attracts a crowd that is young, local and well informed. To access the gallery, located on the third floor of an industrial building, I was, to my amusement, advised by a passerby to take the stairs to avoid the occasionally dysfunctional elevator. In line with its continuous effort to promote emerging artists, “The Imaginary Order” is the gallery’s latest group exhibition, featuring works by budding Hong Kong talents Chen Ting Ting, Andrew Luk and Yip Kin Bon.

Referencing the psychoanalytic term coined by French thinker Jacques Lacan (1901–1981), “The Imaginary Order” explores the mysterious, maze-like process of how we relate ourselves to the external world. According to Lacan, it is a ceaseless process that begins when a newborn recognizes him or herself in the mirror, and an identity of the ego starts to take form. The self, thus, becomes a mediator between the imagination and the fragmented reality. Like the journey of the self, as proposed in Lacan’s theories, the works of the three artists in “The Imaginary Order” tell a story of finding coherence in the midst of chaos.

The exhibition begins with mixed-media artist Yip’s “Inept Archivist” (2013–16), a series based on a semi-fictional archivist that selects, edits and deletes (almost all) information in his care, despite his very duty to collect and preserve data in its entirety. In Blank 002 (2015), newspaper pages hang from a wooden rack. Peculiarly, every single word has been cut out from the pages, leaving precise strips of empty space in between the delicate bars of remaining paper. The display of Yip's works makes it appear as though the goofy archivist had been in the gallery and managed to knock over a filing cabinet—which is in fact part of an installation titled Des Voeux Road West 286-294 (2015). In portraying the incompetence of the archivist, Yip also seems to be making a satirical remark on the absurdity of human behavior.

Throughout the "Inept Archivest" series, consistent use of newspapers reveals Yip’s interest in the nature of the material as a message carrier and a reflection of disorderly reality. His newspaper collage Dimension Variable (2015) is made of over 20 different clippings, with various sections cut out, rearranged and framed. By putting the clippings in a new, overlapping order—one that is independent of the external, chaotic reality—Yip expresses his contemplation of an imagined, less absurd world.

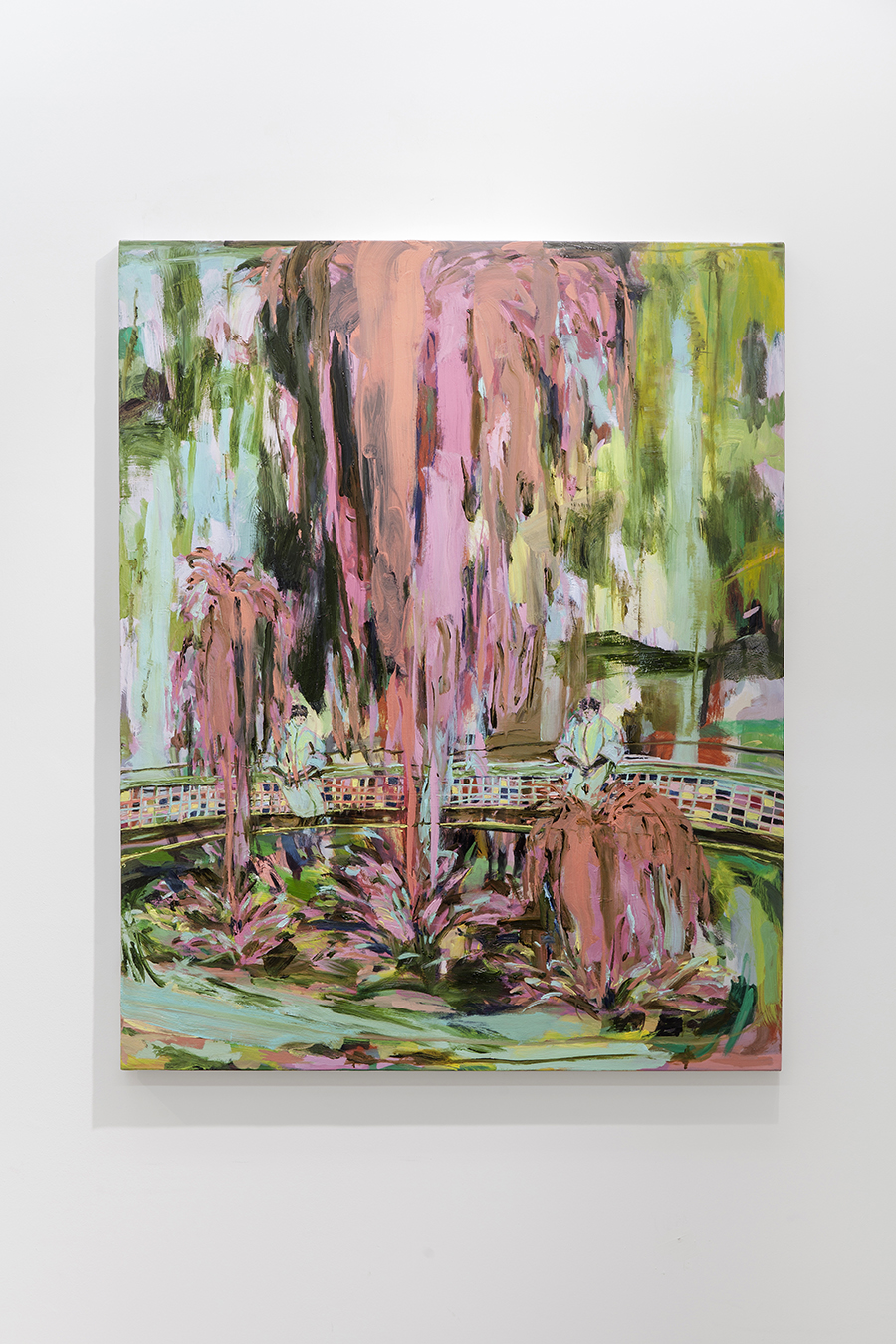

A peer of Yip and a graduate of Baptist University’s Academy of Visual Art, Cheng takes on a painterly approach to communicating imagination in her art. While her subject is often based on daily observations of urban city life—whether it be a dazed receptionist in a commercial building or a middle-aged woman at a public park in the late-night hours—Cheng projects her memories of them in a new light, impassionedly placing focus on the soul that is often neglected in the bustling city. In Cheng’s “Fountain Hall” series (2015–16), five paintings featuring quick brushwork in vibrant colors re-create her memory of visiting a park with her cancer-stricken mother and gazing together at the same fountain everyday. Grand Fountain (2016) depicts two seated figures facing a splashing fountain set against a blurry background. Though Cheng illustrates scenes of ordinary life, her dynamic paint strokes and color palette powerfully communicate her emotional psyche.

Nearby, Luk, a Boston-educated multimedia artist, appears to show pieces that display the two paths that his works take in his practice. On the one hand, Luk collects abandoned objects such as ceramic tiles, wooden planks and blocks of cement from random places, and his treatment of the objects reveals the unique makeup of each material—their physical qualities and historic authenticity. On the other hand, the objects’ treatment can also be seen as an experiment. The process involves setting alight polystyrene—a commonly used foam that releases toxic fumes when burnt—atop the materials, which creates a strikingly abstract charred surface, as seen in his series of six “paintings” entitled “Oxidization Immolation” (2016). Although the result is unpredictable, the process is somewhat instinctive and calculated—the artist explains the outcome is dependent on the amount of water, chemical substances and control of the burning time.

Whether it is Yip’s creation of “the archivist,” Cheng merging her mother’s figure with her own, or Luk’s attempt to control certain aspects of his “experiment,” the ego, in search for coherence, imposes a certain rhythm—an order, or even disorder—on our complex surroundings. By considering Lucan’s theory of the self-conscious, perhaps we can better understand the psychoanalytic mechanism of the imagination in art-making.

“The Imaginary Order” is on view at Gallery Exit, Hong Kong, until March 5, 2016.