Shows

“On the Origin of Art” at MONA

Like most private museums, Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) is a reflection of the tastes of its founder—in this case the sex-and-death inclined David Walsh. Situated in an idyllic spot in Hobart, capital of the island state, MONA is pitched as a subversion of traditional art world institutions. Staid wall labels are abandoned in favor of “art wank” on an iPod guide called “The O,” walls are painted in brooding charcoal instead of gallery-cube white, and rather than wandering grand light-filled spaces, visitors make their way through a series of underground tunnels and caves. Works are grouped by thematic resonance rather than chronology, meaning it’s not uncommon to see ancient relics communing with video work.

While it’s his mischievous character that informs that of MONA, it is the logical side of Walsh that has allowed MONA to exist. Walsh’s mathematical genius has helped him to rake in enough gambling winnings to establish the museum (while raising the ire of the Australian Tax Office). This capacity for logical thinking has informed the temporary exhibition, “On the Origin of Art.”

The exhibition is pitched as “one man’s crusade to piss off art academics,” bypassing the cultural lens by handing the curatorial baton to four scientists in order to investigate art’s biological and evolutionary origins. It’s also possible to read it as a mission to understand how art, with its inherent unquantifiability, can be understood within a logically-framed world view.

Either way, it is a fair question. Is art adaptive? In a somewhat unevolved move it is left to four male scientists to explore: New Zealand professor Brian Boyd, American evolutionary neurobiologist and cognitive scientist Mark Changizi, American psychologist Geoffrey Miller and Canadian-American psychologist Steven Pinker. Their responses are different but overlapping. Boyd sees art as cognitive play with pattern; Changizi believes civilization mimics nature; Miller concurs with Darwin’s explanation of art as a mechanism for attracting mates; while Pinker believes art is a “pleasure technology”—we make it because we can.

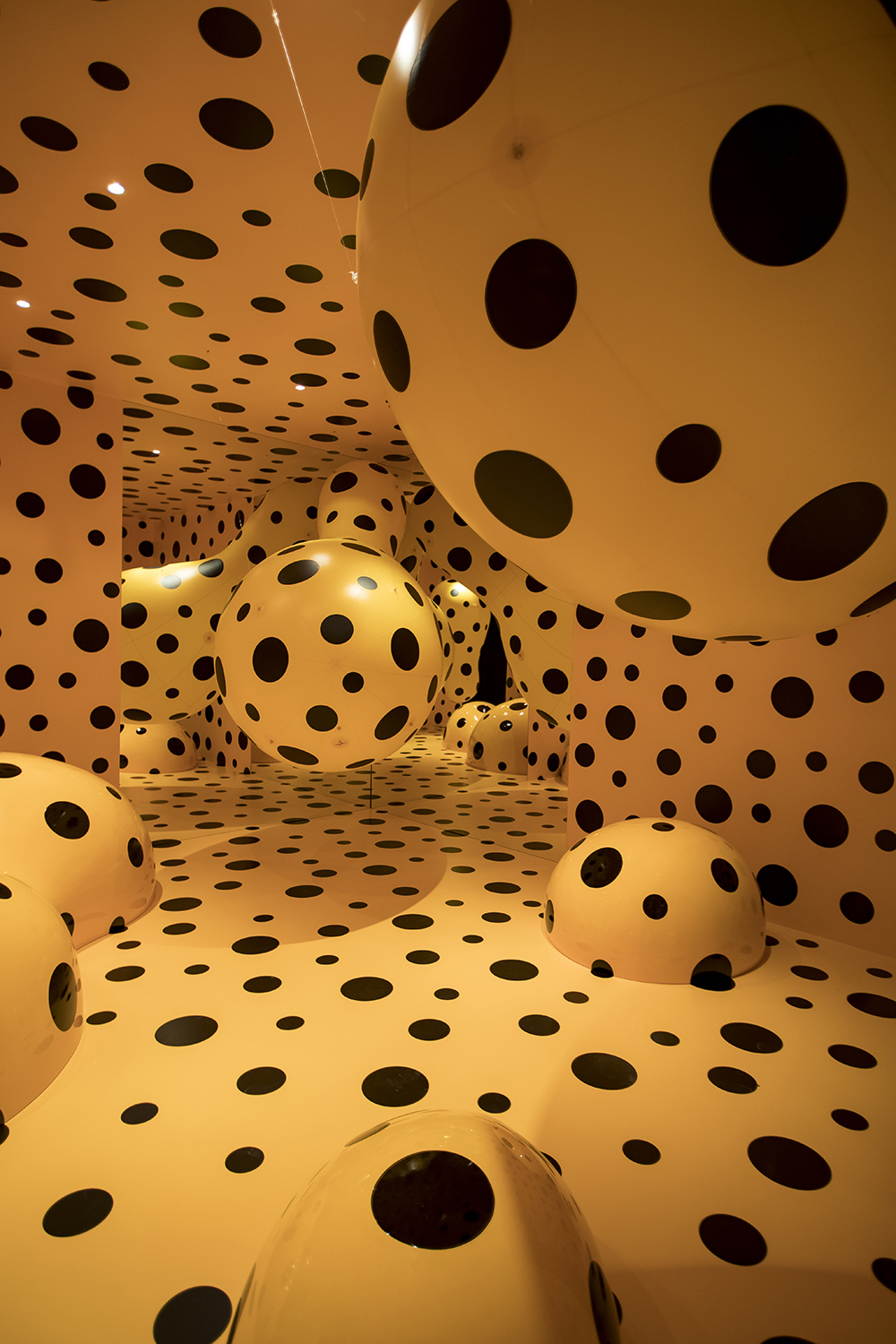

The opportunity for dialogue is opened up between the four curator-scientists, who engage that opportunity to varying degrees. It is refreshing to hear Boyd playfully challenge his fellow curator Miller through the inclusion of certain works. Miller believes Jeff Koons, with his once-porn-star ex-wife, numerous progeny and financial success, to be the pinnacle example of artistic skill as sexual selector—presenting Koons’ 1991 photograph Manet, depicting the artist mid-sexual tryst, to argue his case. Boyd, conversely, throws visitors headfirst into the Yayoi Kusama installation Dots Obsession – Day (2008) in a reminder of art’s ability to dissolve those markers—it’s unlikely viewers are thinking about Kusama’s eligibility as a sexual partner while they explore this mirrored yellow and black universe.

The exhibition, in true MONA style, affords the opportunity to explore some ideas through the juxtaposition of seemingly disparate objects from the prehistorical to the contemporary. As well as the aforementioned Kusama, Boyd gets playful with the inclusion of music videos by the likes of American rock band OK Go and comic strips by Art Spiegelman. Pinker immerses viewers in Aspassio Haronitaki’s installation of x-rayed floral imagery Who Says Your Feelings Have To Make Sense (2016), before offering ancient Egyptian amulets, mounted in gold by a luxury jeweler in the 1920s, as an example of status via conspicuous consumption. Changizi presents a specially commissioned piece by Brigita Ozolins which envelopes viewers in a warm wooden space highlighting the universal patterns of writing and their reflection of natural forms.

For an exhibition designed to challenge the art academy, there is still a fair bit of theory to become immersed in—or wade through. There are more than enough opportunities to listen to the curators’ perspectives or read information on The O as one moves through the exhibition spaces, to the point where the digital interface can get in the way of one’s experience of being physically and mentally present with a work of art—and with fellow audience members. It is an odd testament to the contemporary human condition in an exhibition investigating art’s evolutionary origins.

“On the Origin of Art” at the Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, is on view until April 17, 2017.