Shows

“Nobody Knows Where”

For fans of Chinese cinema, Christopher Doyle needs no introduction. His work as a cinematographer, most notably for the films of Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-wai, has made Doyle a near-iconic figure and a favorite at international film festivals. With Doyle's penchant for ultra-saturated colors and deliberately chaotic camerawork, his aesthetic sensibilities are at odds with Chinese artist Zhang Enli, whom the former has been paired with for “Nobody Knows Where,” an ostensible collaborative exhibition at Shanghai's Aurora Museum. In the exhibition, Doyle, a master of unrestrained, hand-held camera stylings that is now ubiquitous in contemporary cinema, has helped achieve the intensely moody and radically jolting feel and look of Wong Kar-wai's films. Zhang, on the other hand, favors quiet, forgotten domestic scenes; the quality of his paint is thin and ethereal, and the moods evoked are equally elusive. The show’s organizers do not see Doyle and Zhang’s opposing styles as an impediment. Instead, they believe the two artists share a gift for improvisation that imbue their respective works with a sense of natural gesture. Indeed, it seemed that the pairing of the two artists would have had intriguing possibilities; yet, ultimately, the exhibition felt disjointed.

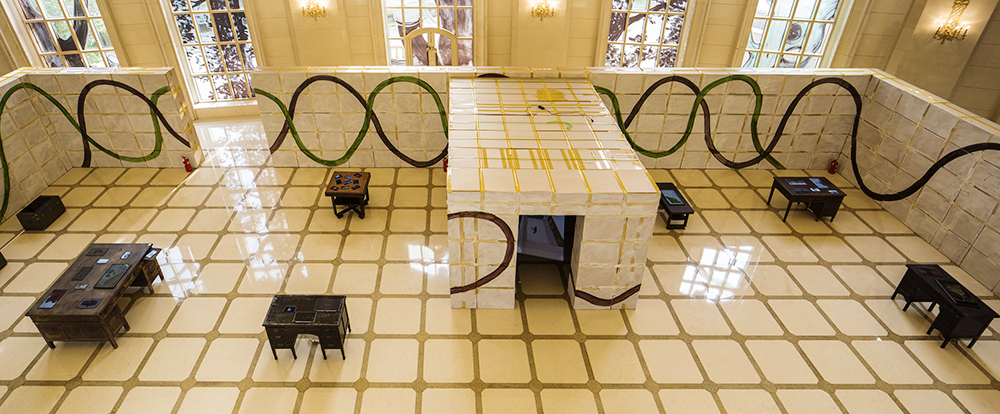

Doyle has, in recent years, increased his presence in fine-art circles with exhibitions featuring his photography, collages and short films. He has taken to photographing abandoned interiors that hint at past glories and creating “moving paintings” from these images. At Aurora, several such works can be viewed in Empty Room, an architectural installation created by Zhang in the museum’s chandeliered lobby entrance. Empty Room comprises the bulk of the show, with Doyle’s short films and other moving images placed throughout the installation. Small screens have been integrated into antique, art-deco furniture pieces, perhaps as a reference to the content of Doyle’s work. His “moving paintings” employ filmic techniques—a rush of ink dissolves expertly into a still photograph, for example—but they are neither particularly innovative nor intriguing. In one series of videos, Doyle and Zhang can be seen interacting in and around Empty Room, climbing over furniture and sitting on chairs, enacting a sort of laissez-faire performance that doesn’t really seem to go anywhere and provides little context of their collaboration. Furthermore, aside from these videos, there is not much else in the show that suggests that the artists had fed off each other or established a working relationship in the run up to the exhibition.

Film fans, however, will delight in seeing the inclusion of a series of candid clips that Doyle took on the set of some his favorite Wong Kar-wai films that he had worked on. One can catch glimpses of actress Maggie Cheung preparing for a scene in In the Mood for Love (2000), or spy on actor Leslie Cheung dancing a solo tango in his underwear on the set of Happy Together (1997). These clips are a reminder of what makes Doyle so revered in the film world. Empty Room itself, however, is baffling, looking more thrown together than carefully curated. Zhang created the walls of the “room” with boxes—in homage to a series of paintings that did of ordinary cardboard boxes—taped together haphazardly with yellow packing tape. The outside walls of the "room" are left as is, while the inside is treated with cursory sketches in Zhang’s signature style. If the idea was to recreate his paintings as a three-dimensional installation, the result is disappointing. In addition, the impressive floor-to-ceiling windows of the museum’s halls have been lined with decals of Zhang’s tree paintings; yet visitors are never afforded a full view of them, since their magnificence is obscured by Empty Room.

Elsewhere in the museum, among its permanent collection of antiquities, a set of Zhang’s signature paintings are displayed across from a set of Tang Dynasty (618–907) clay figurines. The mundaneness of the subjects in Zhang’s paintings—a green tube tangled in string or a stack of rolled paper—play off nicely against the historic artifacts, which were typical objects in their time, but have become extraordinary through the passing of time. This kind of poignant dialogue is missing from the rest of the show. Instead, viewers are treated mostly to two artists exchanged in artistic tomfoolery that never quite gels into a genuine fusion.

“Nobody Knows Where” is on view at the Aurora Museum, Shanghai, until August 30, 2015.