Shows

“Listening to Transparency”

An extensive sound art exhibition with the theme of transparency in the Minsheng Museum’s new home—the former French pavilion of the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai—appeared at first glance enigmatic and ambitious. Yet there was a resonant precedent: Poème Électronique (1958), an eight-minute piece created by French composer Edgard Varèse (1883–1965) for the Philips Pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair. The pavilion in Belgium was designed by the visionary modernist architect Le Corbusier (1887–1965), and around 350 speakers were utilized to circulate sound within the structure, essentially constructing a second, overlapping pavilion that could only be perceived aurally.

Sound was again the crucial element in “Listening to Transparency,” a presentation of 44 works by 26 artists who infiltrated the idiosyncratic architecture with the sonic imprints of their installations, just as Varèse had wanted his sounds to trace the shapes of Le Corbusier’s pavilion.

Pierre-Alain Jaffrennou’s The Fall of the Angel (2003) commanded the vast atrium with a startling vertical red line that was a laser beam. From above, the light pierced the darkness and appeared to fill a glass vessel, while ominous breathing sounds and glissandos of electronic music could be heard from the perimeter of the space. The movement of unseen entities is produced by artfully manipulated sound. Occasionally, they make forays toward the light stream—the installation’s lone unwavering, pure element. It was a theatrical entrance to a show that repeatedly evoked a sense of presence, space and movement, even in the absence of tangibility.

Elsewhere, technological hardware played tricks on our eyes. Ici Même le Temps des Traces Longtemps (2006) by Pascal Frament Jean-François Estager and Henri-Charles Caget is an automated railway carrying a projector that traversed a long gallery, tracking left and right. It was accompanied by complex radiophonic soundscapes as it shone images of urban industrial panoramas on a wall coated with phosphorescent paint. The passing light left a fleeting green glow. The darkness of the room was disorienting. One’s eyes struggled to adjust to catch the faint remnant, which felt like a fading glimmer of the real world.

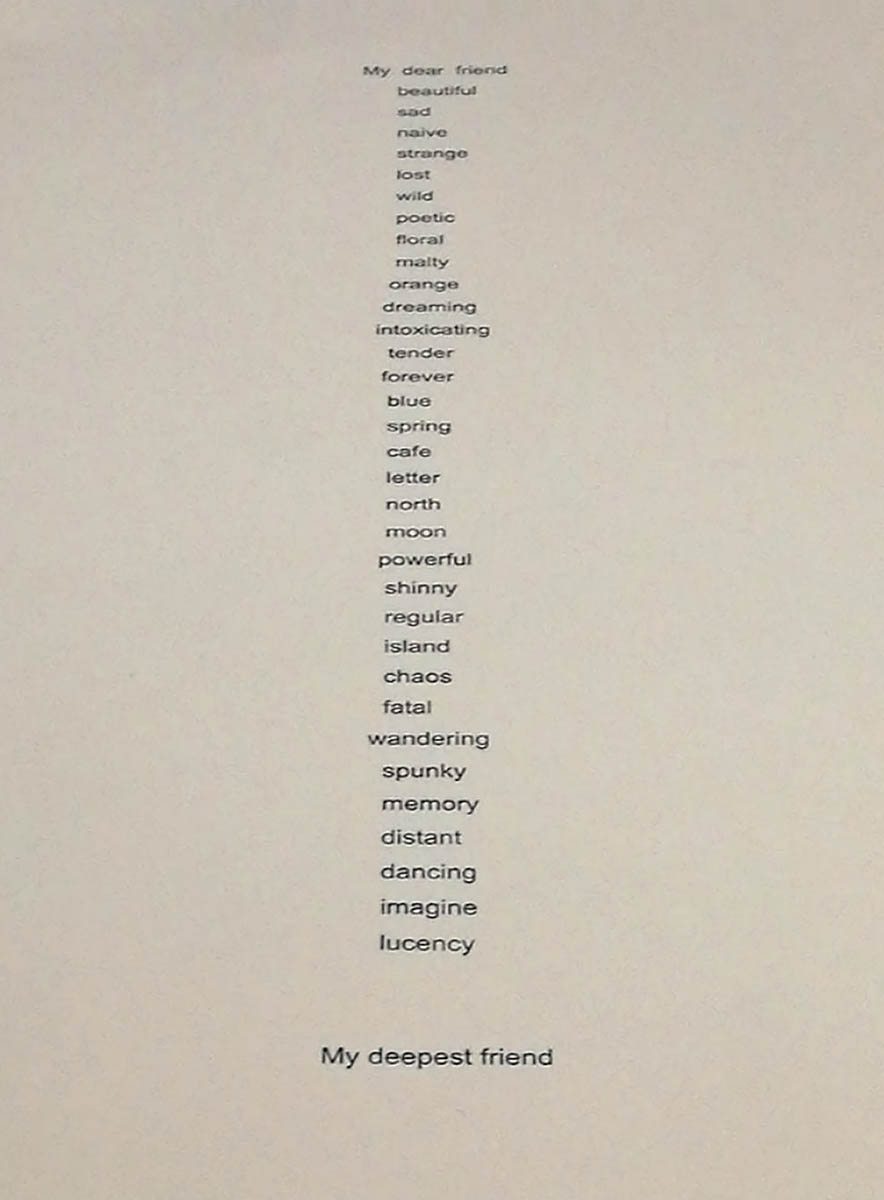

Li Yuhang’s My Friend (2015) was a simple but powerful work that explored the divide between authentic and constructed emotions. It consists of a sheet of A4 paper, beginning with “My dear friend” and ending with “My deepest friend,” with a column of adjectives sandwiched in between. The list is read out on a detached loudspeaker some distance away, with the words being uttered in triplets, such as, “My tender—forever—blue friend.” The problem was that, for all the apparent warmth of this litany, the list is a script, the reading a performance, and doubt is cast on the existence of this friend and the sentiments being uttered.

Other works explored the relationship between sound and aesthetics. Denys Vinzant’s dazzling installation, D’Ore et d’Espace (2000/13), consists of musical scores written in gold ink on plates of glass, providing an experience that is both aural and visual. Similarly, Dominique Blais’s Untitled (White Disks) (2012), a set of suspended sandstone disks that gently collide and grind against one another, evokes an intimacy rooted in earthly sounds and mineral textures.

“Listening to Transparency” implied physical presence by marshaling the spatial orientation of audience and sound source. Visitors moved obligingly with vigilance, careful not to trip on invisible objects. The artifice extended to affections and memories. Transitory feelings, sensations and sentiments were all evoked through the accurate positioning of sound sources, suggesting that judgments are governed as much by where you stand as by what you see.

“Listening to Transparency” is on view at Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, until July 30, 2017.