Shows

Ken and Julia Yonetani’s “The Emperor's New Clothes: Money is at Once Nothing and Everything”

Best known for creating the poignant installation Crystal Palace: The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nuclear Nations (2012–13) featuring fanciful chandeliers made of uranium glass that glow eerily under black light, Ken and Julia Yonetani are a married artist duo who create provocative works that cast their critical eye to hot-button political, economic and social issues. “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” the couple’s current show at Tokyo’s Mizuma Art Gallery, is no exception.

The exhibition title was taken from Hans Christian Andersen’s cautionary tale of the same name which, since its publication in 1837, has become something of an idiom. Oxford Dictionaries, for example, states that “The Emperor’s New Clothes” is “used in reference to a situation in which people believe or pretend to believe in the worth or importance of something that is worthless, or fear to point out an obvious truth that is counter to prevailing opinion.” Andersen’s tale ends with a small child who finally speaks up to question authority; in this exhibition’s rendition of the classic story, the artists play that role of the outspoken child.

Upon entering the space, a crowd-pleasing interactive piece titled The Morphology of Revenge (Look Your Killer in the Eye) (2017) is displayed on a white pillar, which appears to be reserved for the gallery’s one-off favorites. Two seemingly unadulterated American five-dollar bills, placed between Plexiglas, sit waiting to reveal to the viewer what is hidden within its fibers—a message written by the artists that is only visible with the accompanying black light. When shone on the surface of the top bill, the words “The Morphology of Revenge” is revealed. One of the bills is an infamous “red seal” note, printed by the Kennedy Administration in 1963 after the president signed Executive Order 11110. Many conspiracy theorists claim the order was the president’s attempt at stripping power away from the Federal Reserve—an act they believe ultimately lead to his death. The year 1963, therefore, holds strong resonance in this work as it not only refers to the alleged events leading up to Kennedy’s assassination, but also draws parallels with the late Japanese artist Genpei Akasegawa’s well-known work on money Morphology of Revenge (Look Him in the Eye Before Killing Him) (1963). It questions the very act of printing money, the authority that can instill value, and the lengths at which some may go to preserve their power.

Questioning the legitimacy of governing bodies is also seen in the large installation The Emperor’s New Clothes (2017) displayed in the gallery’s main space. Comprised of a sokutai, a formal Japanese court costume, fashioned out of approximately 1,000 one-thousand yen notes, the overwhelming size of the attire includes a long train of yen affixed to the floor. Here, the sokutai represents the Imperial family and the Emperor’s pervious might in monetary control, yet, it simultaneously undermines such grandeur by constructing the dress out of low-denomination currency with the modern government’s imagery and trailing the bills on the floor. Such display suggests that much like the power the Emperor once held, it can be stripped away at a moment’s notice. The Emperor was also referenced in a series of works nearby called “Kami (Paper/God)” (2017). The individual pieces are antique frames that Ken and Julia sourced from around Japan, which were once used to mount official portraits of the Japanese Emperor. In each frame, the artists have now covered the portrait with a single yen bill, playing on the Japanese word kami, which means both “paper” and “god.” In this way, the artists allude to the way money has become an idol of worship in contemporary society.

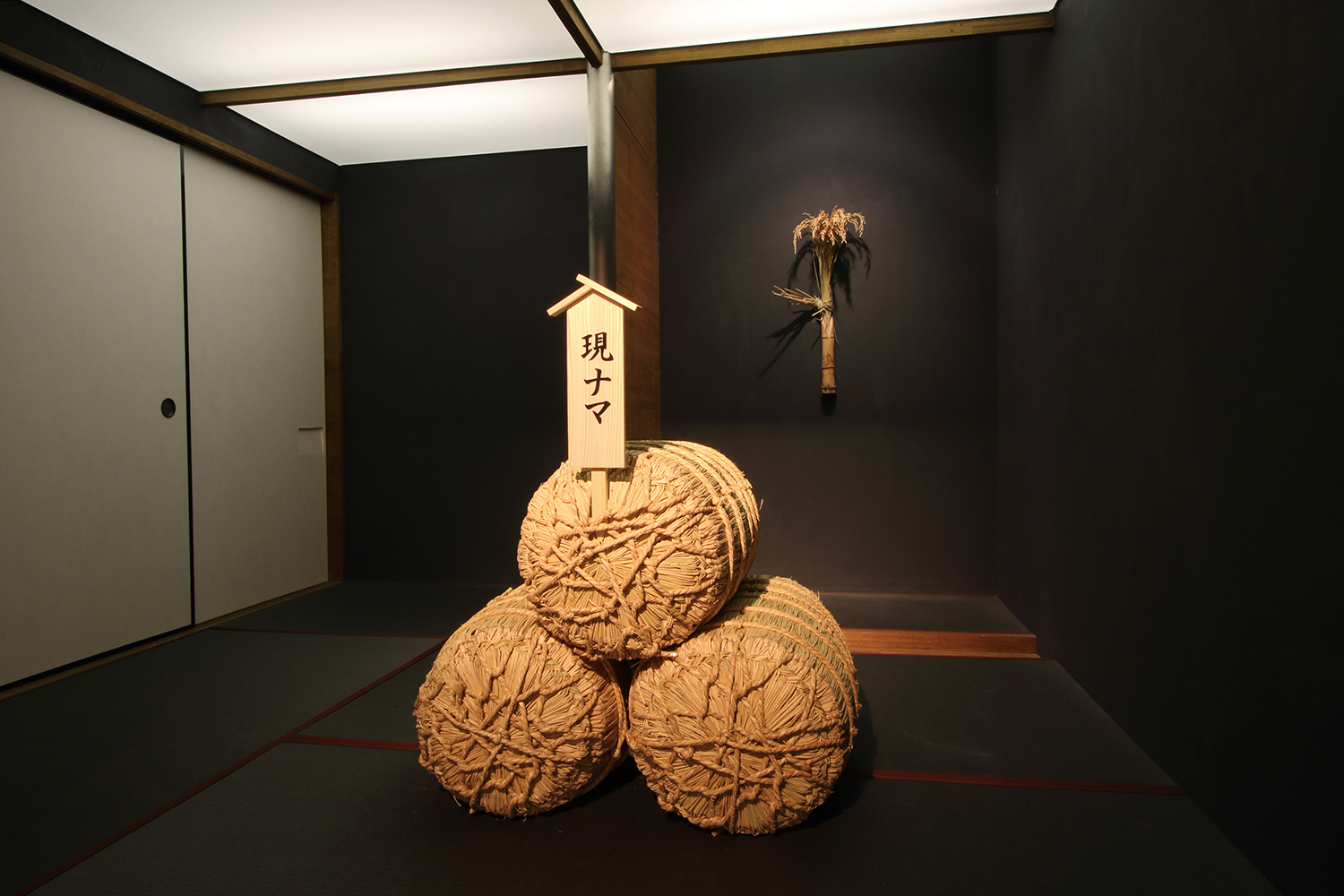

The space of Mizuma Art Gallery is well known for its traditional Japanese tatami room, in which the gallery invites exhibiting artists to create a site-specific work. By default, the work has a distinct Japanese influence—whether in design or by association. Encountering the tatami is a refreshing change given the monotone white-cube galleries commonly seen in the art world. Ken and Julia’s work in this room Gennama (Hard Cash) (2017) highlights the original aspect of the tatami and showcases tawara (baskets of rice), which traditionally represented salary payments during the Edo period (1603–1868) when the grain was used as currency to settle taxes. By filling the tawara with rice grown on their own organic farm in Nantan-shi, Kyoto, the work foreshadows the nation’s return to rice, should the yen collapse, and seamlessly blends economic concerns of the past with the present.

Zooming out of Japan, the artists relate these financial topics to our current global environment. In Stimulus Package (2017), men’s briefs from the Australian brand Bonds are displayed on hangers to represent the G20 member countries. The use of Bonds, in this instance, touches on bonds in an investment sense, which many governments rely on for debt security. Complete with flag patches on the groin and each country’s debt handwritten on the price tag, the works poke fun at campaign promises and debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios that weaves us all together, regardless of nationality.

“The Emperor’s New Clothes” presents work that may appear simple in its construction yet complex in presentation, and this successfully translates Ken and Julia Yonetani’s goal of challenging viewers to hold their government accountable. It is a thought provoking experience, highlighting the common theme (and problem) of money. While the works may appear overtly critical of our global economy, the couple, who are parents to two young daughters, are making an underlying statement about hope, and a call to action that will move citizens to question, act and demand a better future.

Peter Augustus is associate publisher at ArtAsiaPacific.

“The Emperor’s New Clothes” is on view at Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo, through March 25, 2017.