Shows

João Vasco Paiva’s “Cast Away”

João Vasco Paiva

Cast Away

Fundação Oriente

Macau

Since its origins a century ago, modernist abstraction has navigated between two poles: hyper-rationalism and romantic transcendentalism. Today, however, when so many of our formative explorations into the unknown are conducted in the digital realm—where the technological sublime inspires as much (if not more) wonderment than nature—the two are no longer such oppositional coordinates on the map.

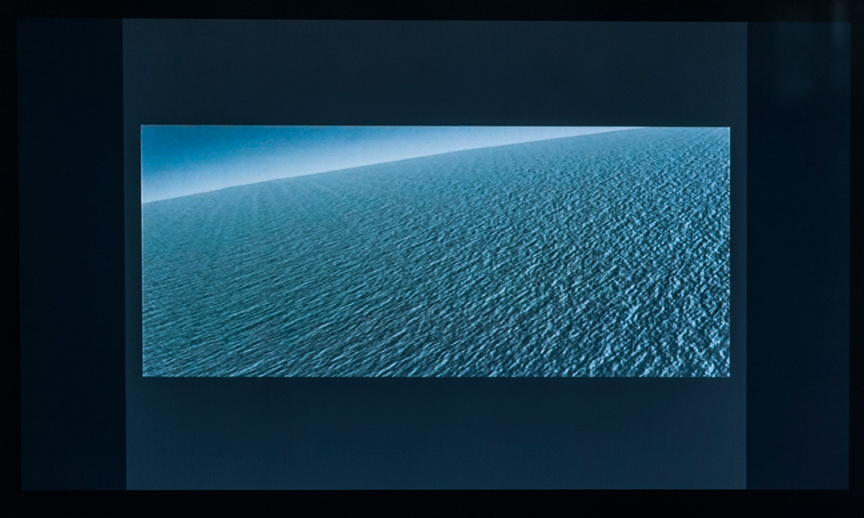

At the heart of “Cast Away,” an exhibition at Macau’s Fundação Oriente by Hong Kong-transplant João Vasco Paiva, is a two-channel video, Unlimited (all works 2014). One screen shows an animation of a flight over the ocean captured from a Google Earth voyage over an undistinguishable watery expanse—Google Earth projects sunny, calm skies over most of the globe, in spite of reality. On the flipside of a walled partition is a rapid projection of different maritime signal flags, geometrical designs that correspond to letters of the alphabet and are used to broadcast a ship’s conditions, such as “man overboard” or “dragging an anchor.” Together, the two projections are digital-era re-imaginings of aspects of the European exploration and colonialism that gave birth to trading outposts such as Macau and Hong Kong—the seemingly endless expanses of ocean that sailors endured along the way and the new communication languages developed while circumnavigating the globe.

The title “Cast Away” takes on other meanings across the exhibition’s four rooms. Paiva placed resin “casts” of flotsam collected from Hong Kong beaches (the artist lives on Hong Kong’s Lamma Island) on top of six light-box-topped pedestals, causing the blue and purplish objects to glow in an eerie, artificial manner. He made a stone-resin copy of a piece of Styrofoam packaging, which stood on its end like a cubist sculpture or a futuristic skyscraper. In opposite corners were four, small dark-blue forms, Seafoam, molded from the rounded bits of plastic that circulate the oceans like the mariners of old—and occasionally wash up on shore, where, like many a salted sailor, they are not always a welcome sight. A gray resin cast of “blind spots” (those circular-dotted panels in the floor that indicate to the blind to stop walking) functioned like a floor mat at the entrance—it was unclear whether this was a found object—and combined ideas of a charting journeys through the unknown.

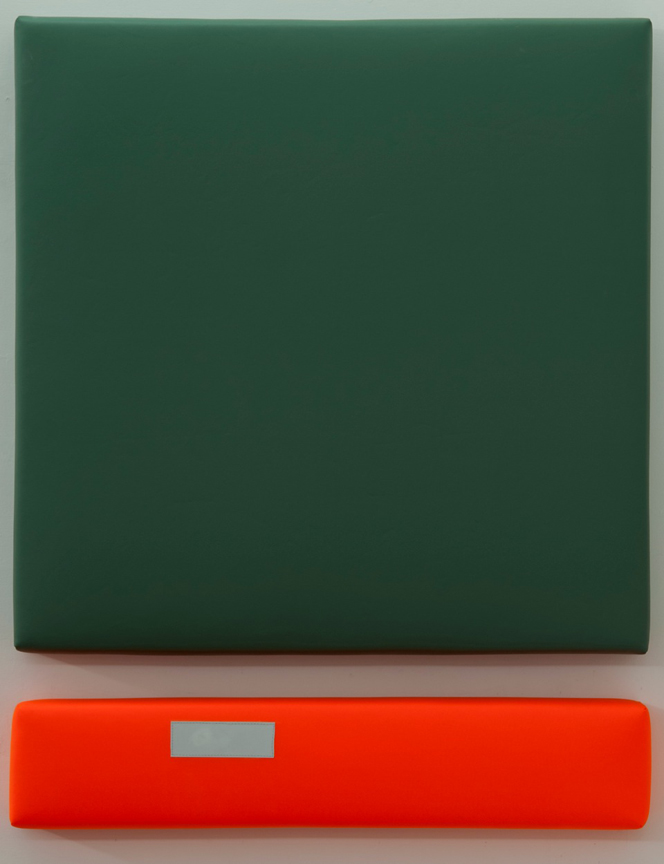

On the walls of the galleries were various riffs on abstract painting. A triptych of canvases—entitled “Portolan I–III,” which were the early navigation charts made by Italian, Spanish and Portuguese explores—are made from old sail cloth, their brown stains resembling coastlines found on the old maps. Safety / Comfort I & II are a pair of paintings that comprise a square made from sea-green and a deep-blue vinyl seat-cushions with a rectangular bar hanging beneath them in orange life-preserver material, marked with a lone reflective strip.

If Paiva’s formal language is austere, and the objects at first somewhat unyielding of their latent stories, most of the pieces in “Cast Away” achieved their own integrity, tracing unexpected threads still linking the early, economically motivated explorations by Europeans around the globe and the modern-day, international economy—largely through all the garbage humans have left in the wake of their travels.

The one piece that fell flat was the largest installation, Shelter, consisting of a four-by-seven-meter carpet of small blue squares of varying tones—like a pixilated oceanscape—with a gray fiberglass form resembling the stern of a small, largely submerged sailboat. As the title suggests, the artist intended the latter form to evoke a refuge—though how, exactly, given the angle of the ship, and why a small, sinking sailboat would double as a haven is unclear. As happens all too frequently with artists today, when realizing large-scale fabrications, objects start to look like stage props—that is, they become more illustrative and less tactile or precious. In the case of Shelter, perhaps the two parts would have looked better on their own within the exhibition, but together their industrially fabricated qualities suggested the artist himself sailing too far from familiar shores. Nontheless, one hopes that Paiva’s explorations into the fertile, peculiar territory of Macau are just beginning.

João Vasco Paiva’s “Cast Away” ended on June 7, 2014.

HG Masters is editor at large at ArtAsiaPacific.