Shows

Huma Bhabha at Stephen Friedman

Huma Bhabha’s latest exhibition takes over both gallery spaces of Stephen Friedman in London. Best known for eclectic bricolage sculptures incorporating myriad collected materials, often protruding from a mass of adhesive or clay, a single work by the Karachi-born, New York-based artist can suggest many themes given her exhaustive field of influences and sources. This show of new works at Stephen Friedman however, marks a change of focus in Bhabha’s practice, where her technique of built and assembled sculpture shifts to carving into the material directly.

Bhabha’s earlier works, such as Sell the House (2006), squashed their materials and references together. In this particular instance, brick, wire, metal bars, wood, polystyrene and an old mop are held together with congealed clay to form a bust on a wobbly stand; resembling a Girls’ World doll in collision with Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899). The head simultaneously hints at sci-fi props, votive images of the Hindu deity Ganesha, Venetian masks and the rakish iconography of Lana del Rey; it is overload with recognizable associations. By contrast, the figure sculptures in Bhabha’s new show present clean lines and poise, carved in the round from monumental blocks of material; they are sparsely embellished with markings in aerosol and crayon. These latest pieces evoke the integrity of archaic prototypes.

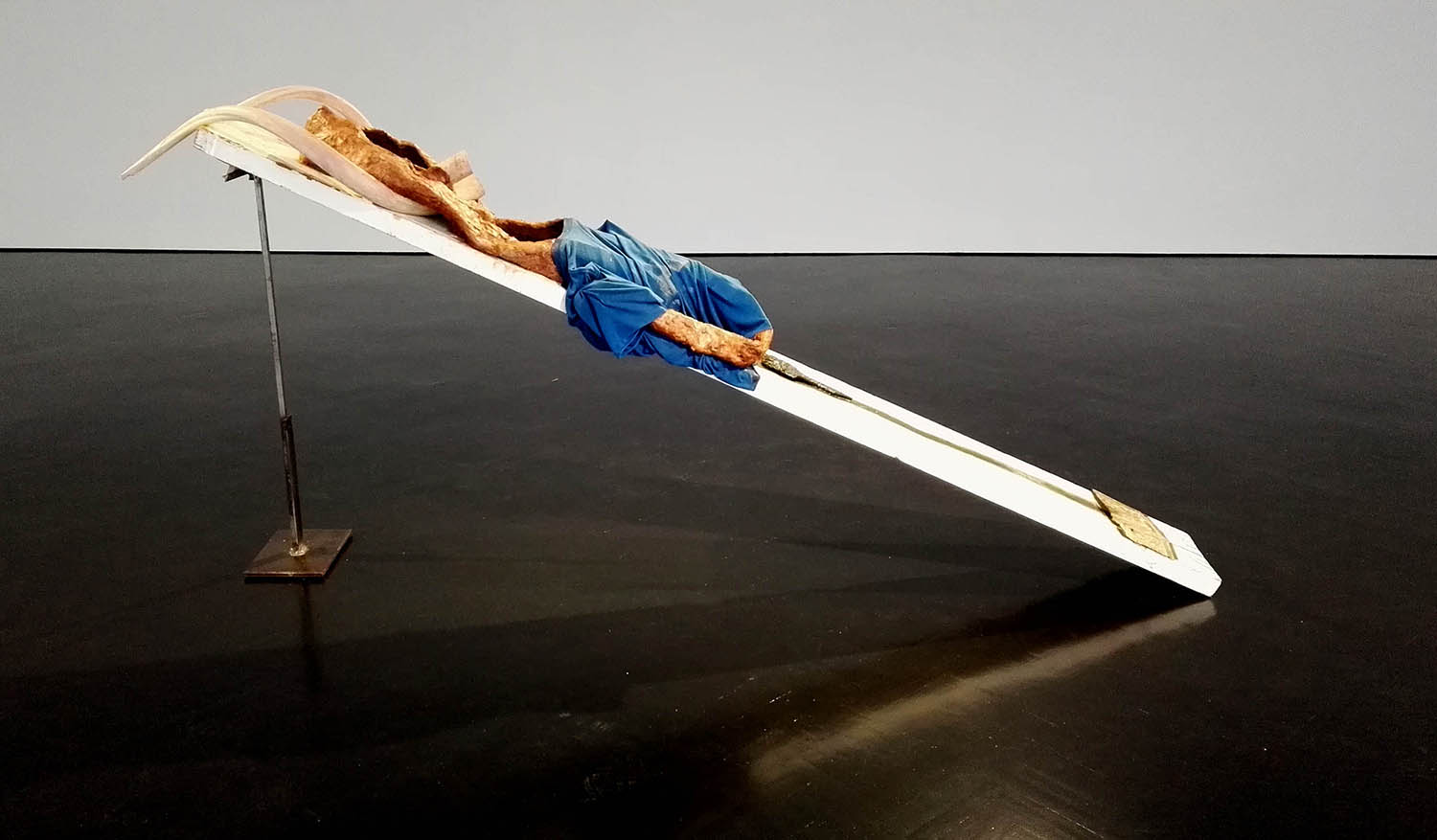

Alone in one of the galleries is Special Guest Star (all works 2016), a slender androgynous figure represented by a diagonal white plank propped up by a metal rod, which acts as a bridge to Bhabha’s earlier practice. The figure has a distended mask-like face made of terracotta clay. The rest of the work is highly simplified: pierced with two ugly tubes, they could be either nostrils or eyes, and surmounted with real animal horns. The figure wears a filthy blue T-shirt pulled taut over a rectangular block. The title is ironic; although the method is the assemblage of classical modernism, the resulting sculpture looks like a caricature of a cubist figure in a torture scenario. This body is wrung dry, everything squeezed out by the stylistic tactics of modernist distortion—the tendency for 20th century transatlantic art to aggressively twist the appearances of subaltern cultures.

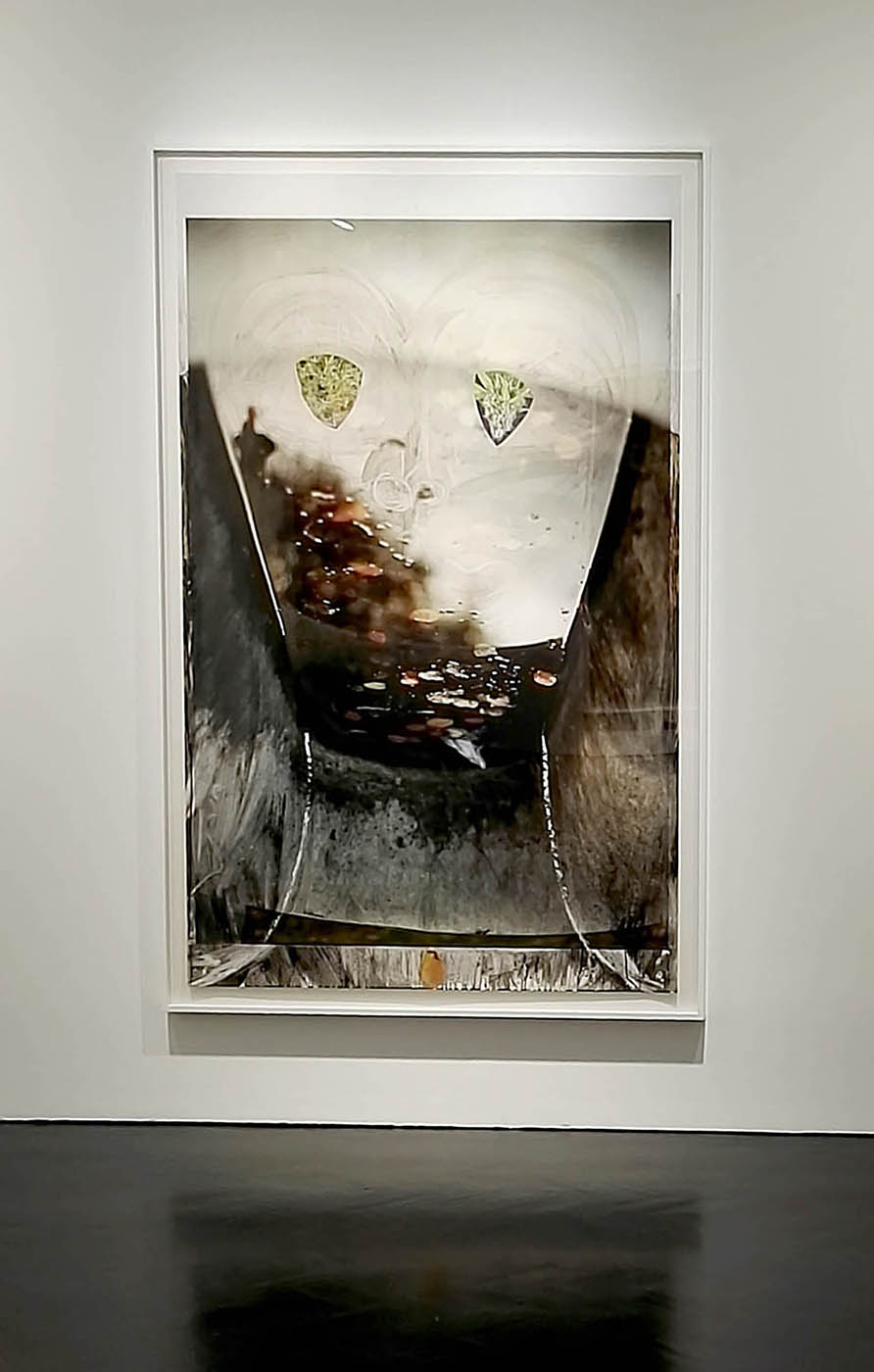

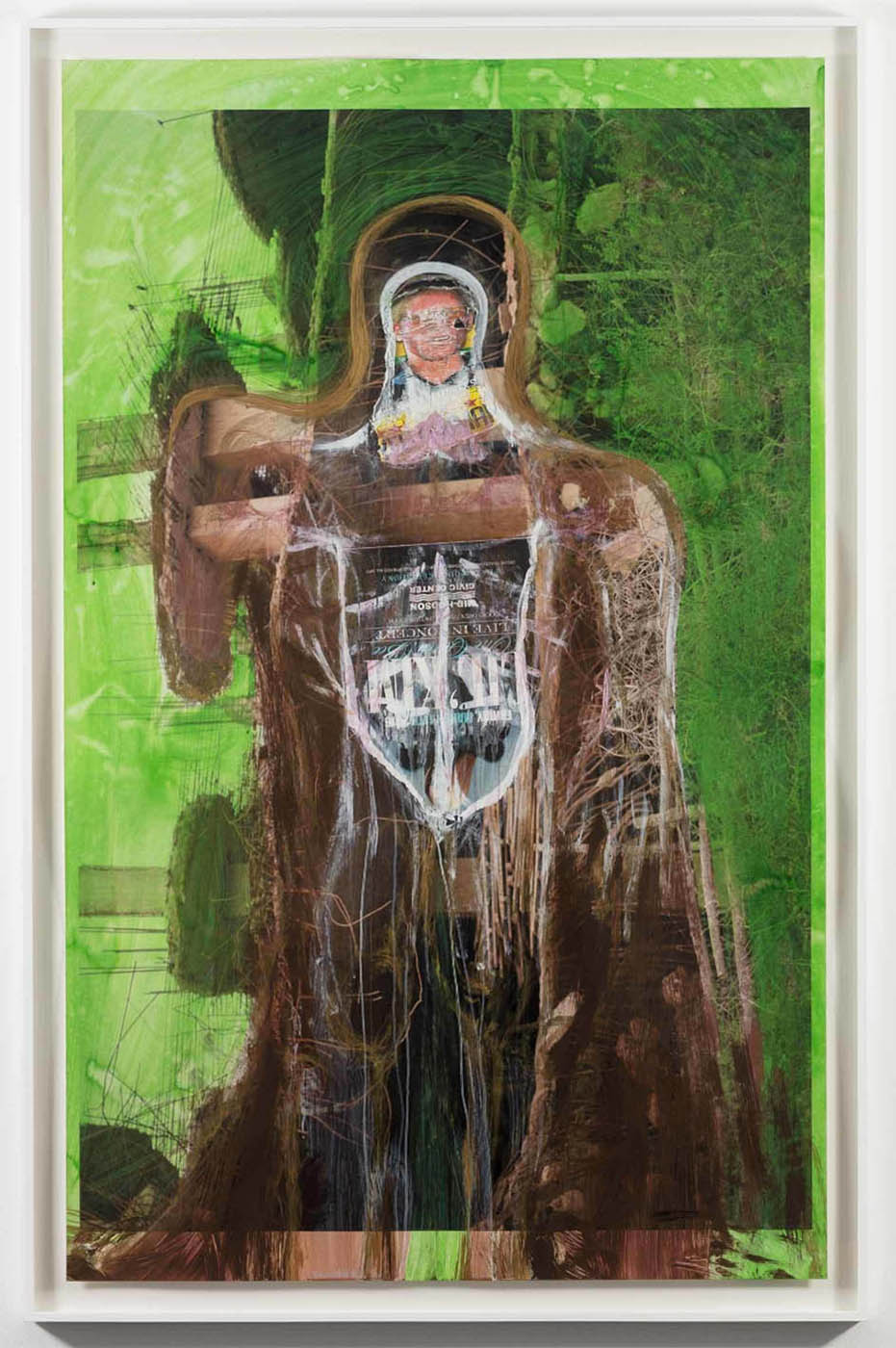

In four tall untitled photographs displayed in Stephen Friedman’s other gallery across the street, Bhabha references another modernist strategy, image association, as seen in Max Ernst’s frottage, but the figures she summons are not visual but spiritual. The source images are nondescript landscapes, trenches and muddy pools taken in Berlin and Karachi. Bhabha has dragged schematic larger-than-life figures from these unpromising scenes, created with much agitated activity, nearly expunging the photographic image altogether but providing scant characterizing detail in the overlaid image. They are hazy types, phantoms rather than people. One photograph, composed partially with magazine images of marijuana plants, is just an oversized head. The approach is not imaginative but cathartic, freeing a spectral human essence by purging the image content of the photograph.

Bhabha applies a similar method to develop two full-length figurative sculptures, In the Shadow of the Sun and Castle of the Daughter. Just as the photographic surface has been energetically worked to draw out new presence, the sculptures appear to be produced in the tradition of Germaine Richier and Elisabeth Frink. Both modernist sculptors worked in raw plaster, building an approximation of the form, which was then carved back. When their sculptures embodied the damaging conflicts of WWII, the act of smoothing the rough surfaces became a gesture of affect and repair. The lower parts of Bhabha’s figures are made from friable dark cork and a clear division separates this from their torsos, sculpted in Styrofoam and polystyrene. The effect is that the lower section looks waterlogged while the upper part appears parched. The dark patina on the cork is achieved by burning the surface, emitting a residual odor that contributes to an apocalyptic mood. Castle of the Daughter, in particular, has three strata, with its bloated head made of cork suggesting that the figure has endured a sequence of natural disasters—flood, drought and flood. When a global warming catastrophe strikes the two figures are prepared; both wear bikini tops and their buttocks are buoy-like and marked with circles bobbing at the waterline—they are going to float. They will be rafts as well as survivors who can rebuild civilization and reseed culture as both figures bear their genitals in a gesture of fecundity.

A congested circulation of old cultural influences fueled Bhabha’s previous work, generating many teasing ambiguities. The new twin sentinel sculptures in this exhibition are pared back to bigger concerns—time, individual empowerment and collective disaster. Looking shy but not retiring, these new personages are optimistic, embodying conditions of the present and hope for the future.

Huma Bhabha is on view at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, until January 28, 2017.