Shows

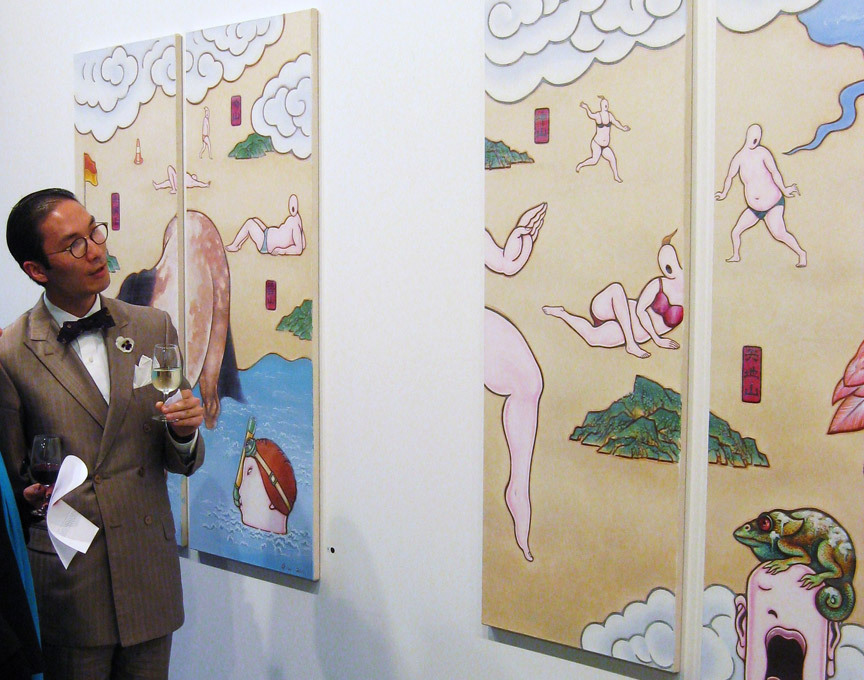

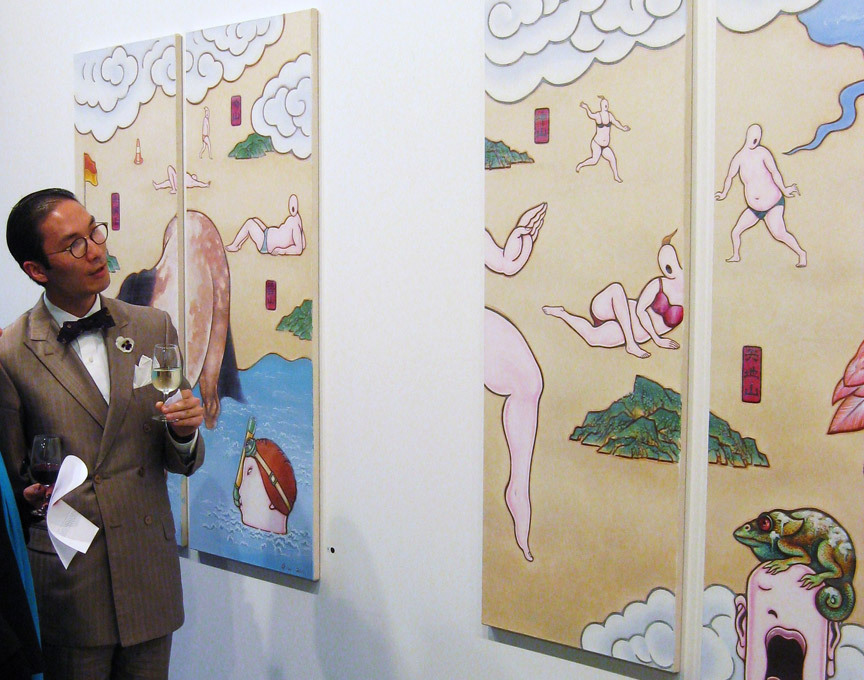

Guan Wei’s “Play on the Beach”

Since returning permanently to China in 2008, Australian-Chinese artist Guan Wei’s life has been in upheaval. He has suffered the economic burden of two government-mandated demolitions of his studio—the second of which occurred just last May, when he described his personal trauma to ArtAsiaPacific. On that occasion he was given only three days to relocate.

For the last three months Guan has been back in Sydney preparing a solo show, “Play on the Beach,” his first with Paddington’s Martin Browne Gallery, which was opened on October 11 by actress and friend, Cate Blanchett. The Hollywood star has a couple of Guan Wei paintings, including Target (2004), a 20-panel piece over five-metres-long that she says had her architect throwing up his hands in despair when he heard the size of the wall it needed to hang on.

His brief retreat to Australia, where the artist originally moved to in 1990, has illustrated to Guan the sharp contrast between Beijing and Sydney. The sense of trauma and conflict he felt under the gray, polluted skies of the Chinese capital has been replaced by an overwhelming sense of sun-drenched well-being and tranquility. In the catalogue, Wei explains: “bright sunshine, floating clouds, transparent seawater, the enchantment of the beach, all combine together to reveal a picture of nature and harmony, lightness and joy.”

The artist’s familiar concerns—the treatment of repressed minorities, the plight of asylum seekers, migration and how history is mediated by any number of political imperatives, evident in works such as Echo (2006) or A Distant Land No 3 (2006)—play no part in the 32 canvases in “Play on the Beach.” The imagery may seem familiar as he uses the same semi-human characters and idiosyncratic animals, but now they frolic, lounge and enjoy life by the water. The once important political imperatives have succumbed to a world preoccupied with sun, sand and surf and his perception of an Australian culture always at play.

Guan’s sojourn has also loosened his tongue. When he was peremptorily ejected from his studio in May, he was reluctant to speak out publicly for fear of official reactions in China. At the October opening in Sydney however, he openly criticized the actions of the Beijing government on opening night; a bold decision considering Chinese consular officials were in the audience. That evening, gallery director Martin Browne also chose not to display the exhibition catalogue, in which Guan criticized his evictors in print.

Yet, Guan’s current works, however pretty, fail to go far beyond their decorative appeal. He is known as a storyteller, for the way he combines a politically sensitive narrative with a refined historical aesthetic. None of this is found in the current exhibition. Moreover, the sand scattered over the floor in one of the gallery’s rooms, meant to evoke the beach, adds little to the experience other than inconveniently getting in one’s shoes.

Guan Wei’s life in Beijing has undoubtedly been tough, but his popularity in Australia remains strong—20 of the works had already sold before the opening. One is hence left with the feeling that this exhibition was meant to capitalize on his reputation in his once adopted country. While “Play on the Beach” has been a commercial success, and is pleasing on first encounter, it leaves only a bland aftertaste.