Shows

“Considerate Creations: Chameleons”

“Considerate Creations: Chameleons” presented by New York’s Taipei Cultural Center (TCC) in New York City’s Taipei Economic and Cultural Office spotlights three women artists and the dualities they inhabit as working professionals. When curator Lee I-Hua originally conceived the idea for a group exhibition two years ago, she reached out to women who happened to work as art administrators in addition to being artists, curious to find out how their day jobs impacted their creative process. At TCC, Chiu Yu-Chen, Hu Nung-Hsin, and Wong Kit Yi—all New York transplants—share recent projects that address the theme of ever-shifting identities.

Moderating the artist talk at opening, the German-born, Brooklyn-based Franziska Lamprecht kicked off the event by asking whether the show’s title in Chinese—“Duō qī” (多棲)—aligns with its English version. While the Chinese term relates to versatility and the ability to inhabit disparate environments, Chiu said she interpreted the meaning through the lens of globalization, which requires individuals to play more than one role. In a biographical sense, she refers to her traditional Taiwanese upbringing, which she felt was at odds with the desire to leave her family and study abroad as a young adult. Her lived experience of internalized cultural conflict materializes in the black and white photographs that quietly yet keenly seek to observe the surrounding world that is her adopted home. In Pursuit of the Sun (2011), from the photo series “Breukelen” (2011), captures a moment of intimacy, even as the silhouetted figures of a man and a woman appear to be walking away from the viewer. Shot along Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, the photograph was used as the cover image for the Chinese edition of Paul Auster’s novel, Invisible (2009), a copy of which sat on display in the show. Likewise, the black and white photograph of children playing in a snow-covered park, entitled Childhood (2006), is shown next to the Chinese edition of EL Doctorow’s World’s Fair (1985), which boasts the photograph on its cover. As a result, Chiu’s fine art photography takes on a second life for editorial and commercial purposes.

Another Taiwanese-born artist who also made her way to New York, Hu, revisited an older work, Sushi (2012), which she first performed in Manhattan’s bustling Union Square. Transforming herself into a piece of raw fish, and lying prostrate on a rotating platter, she mimicked the plastic props often found in Japanese restaurants used to “arouse the imagination of the real taste of food.” The multi-faceted spectacle considers not only the issue of a woman’s body being regarded as a literal slab of meat, but also the meaning behind an Asian artist dressed as a stereotypically Asian food not of her own cultural heritage. Hu said she often invites other women of different ethnic backgrounds to perform with her, thereby intentionally creating a confusion of identity and satirizing the perceived interchangeability of all Asian women.

In Amphibian (2016–17), Hu replicates the performance, but with neither costume nor audience. Performed during the Queens Museum’s off-hours, and documented through security cameras, the artist abandons the public spectacle of Sushi for something more private. The location of the so-called “invisible performance” also bears significance, as it is where Hu works in an education and curatorial capacity. In this way, she draws attention to the often-unseen labor that goes into the making of a show. She reconciles these two halves of her personality—that of the artist and the arts administrator—through two photographs placed side by side, and the use of a stereoscope, which creates one unified if somewhat blurred image.

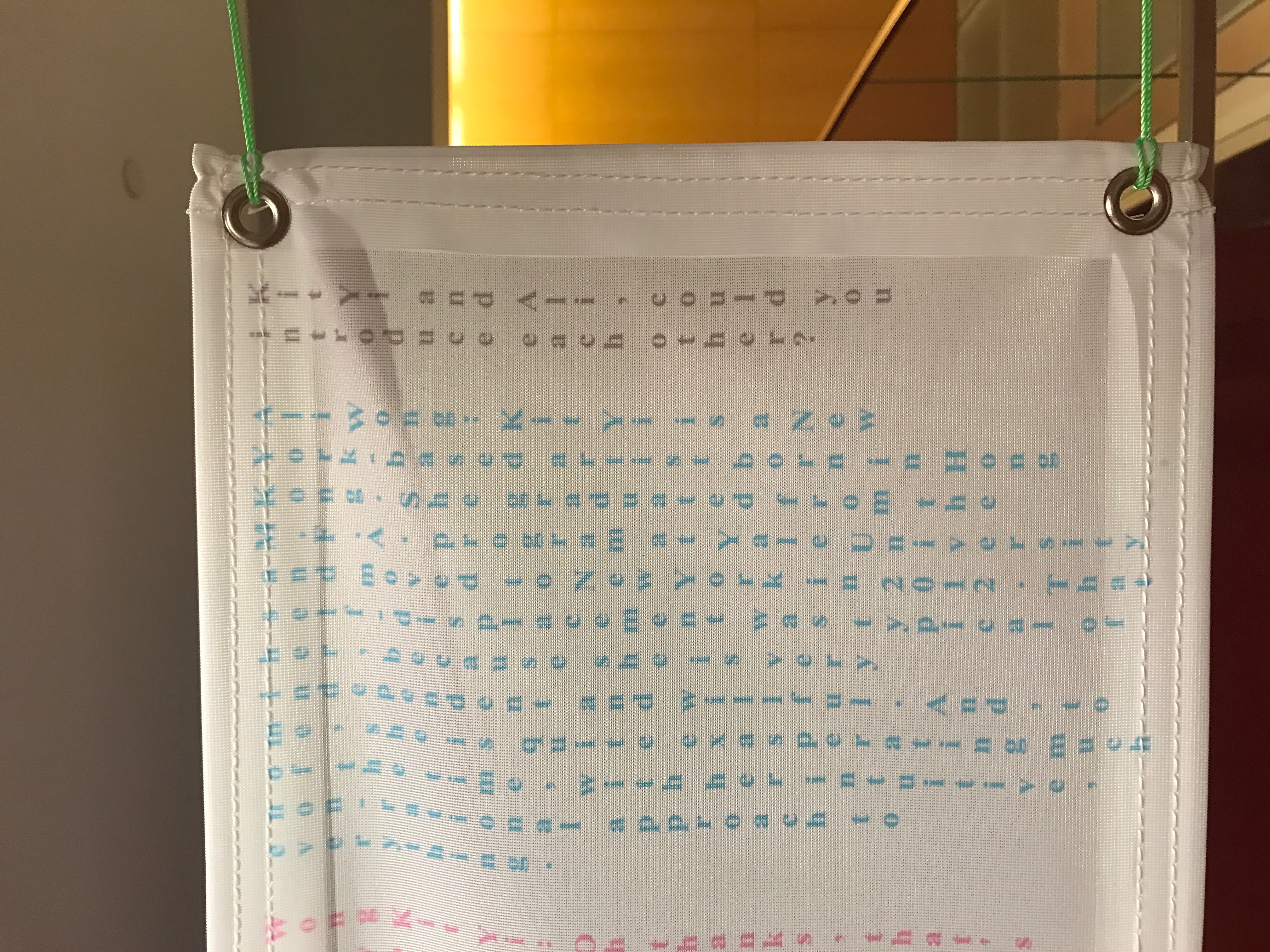

The only native Hongkonger among the group, Wong Kit Yi, advances the concept of dual personas even further. When introducing her, Lamprecht read separate biographies for both the artist and her arts administrator counterpart, otherwise known as Ali Wong, then finished by stating: “They both share a website, they both share a Facebook account, and they both share a body.” While Wong describes the Ali side as someone who feels satisfaction from completing a task, the Kit Yi side tends to favor “never-ending” creative projects, often spontaneously devised. “In Chinese, we say you think twice before you take action,” Wong said of her tendency for self-doubt. Every System Breaks: Ali Wong & Wong Kit Yi in Conversation with Berny Tan (2017) offers further insight into that internal dialogue between Ali Wong and Wong Kit Yi, as facilitated by Singaporean artist and writer Berny Tan. Printed vertically in English and intended to be read right to left like traditional Chinese text, the banner also alludes to the identity crisis of Hong Kong—a former British colony now in the shadow of China.

At the conclusion of the artist talk, Wong returned to the interrogation of her two selves, asking, “Are you trying to fit in the role, or are you trying to create whatever you want to create?” While each artist attempts an answer through her creations, the dilemma underlying these multiple roles perhaps speaks to the difficulty of surviving as an artist in modern-day society.

“Considerate Creations: Chameleons” is on view at Taipei Cultural Center, New York, until April 28, 2017.