Mutter, Ich Bin Dumm!: Biography as Fiction in Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s “Reflection Paper”

By Hendrik Folkerts

Installation view of "Reflection Paper" at the Kunstverein fur die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Dusseldorf, 2021. Photo by Katja Ilner. Courtesy Kunstverein fur die Rheinlande und Westfalen.

I am looking at a painting by the Chicago-based Surrealist artist Gertrude Abercrombie, Self-Portrait of My Sister, created in 1941. The woman has sharp features, an elongated neck, and her gaze projects onto an unknown horizon beyond the picture frame. The radiant blue of her eyes echoes the green and blue of her dress, collar, and hat, the latter adorned with dark purple grapes and a corkscrew. Her lips are pressed, giving her face a stern, austere expression, in subtle contrast with the playful gesture of her right hand embracing her left wrist. Tellingly, Abercrombie was an only child. The artist used self-portraiture to create an alter ego, an imaginary sister—was she smarter, prettier, meaner, or more real somehow? In her records, she would refer to this painting as “Portrait of the Artist as Ideal,” stating: “It’s always myself that I paint, but not actually, because I don’t look that good or cute.” The painting reminds me of Evelyn Taocheng Wang, and all the other possible Evelyns envisioned by Wang.

GERTRUDE ABERCROMBIE, Self-Portrait of My Sister, 1941, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 55.9 cm. Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

STUDIO E.T. WANG, DO NOT AGREE WITH AGNES MARTIN ALL THE TIME (Overall), 2021, artist’s print, dimensions variable, produced on the occasion of "Reflection Paper" at Kunstverein fur die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Dusseldorf, 2021. Photo by Roman Szczesny. Courtesy Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

Evelyn’s work engages with the age-old philosophical question: what if we are fiction? Fittingly, Evelyn has invited me to virtually— fictionally?—attend her latest exhibition, “Reflection Paper” at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen in Düsseldorf, since I cannot visit in person. The exhibition is modeled on a clinic. Will I be treated, healed, or transformed? As Evelyn starts our tour, I am distracted by her outfit and underwhelmed by mine. She is meticulously dressed, wearing black trousers and elegant brown leather shoes, erring on the masculine side of the fashion spectrum. A square-cut, double-breasted tweed jacket with a black vest and a white blouse (buttoned up) underneath completes the fastidious ensemble. Her make-up is clean, understated. The pièce de résistance is a modestly-sized black hat that rests on the right side of her head; it is embellished with a blush-pink faux-flower that resonates with the shades of rouge that I see painted in large circles on the walls of this gallery-turned-clinic. I, on other hand, am wearing sweatpants and a rather dismal-looking Adidas sweater. I have no shoes on. I am truly ready to check into this establishment. Pay attention! Evelyn introduces the exhibition. “So now I would like to walk away for a moment, but I believe your eye will follow my step. And I would like to give you a really cozy and special evening.” Let the Ausstellungsrundgang [exhibition tour] begin.

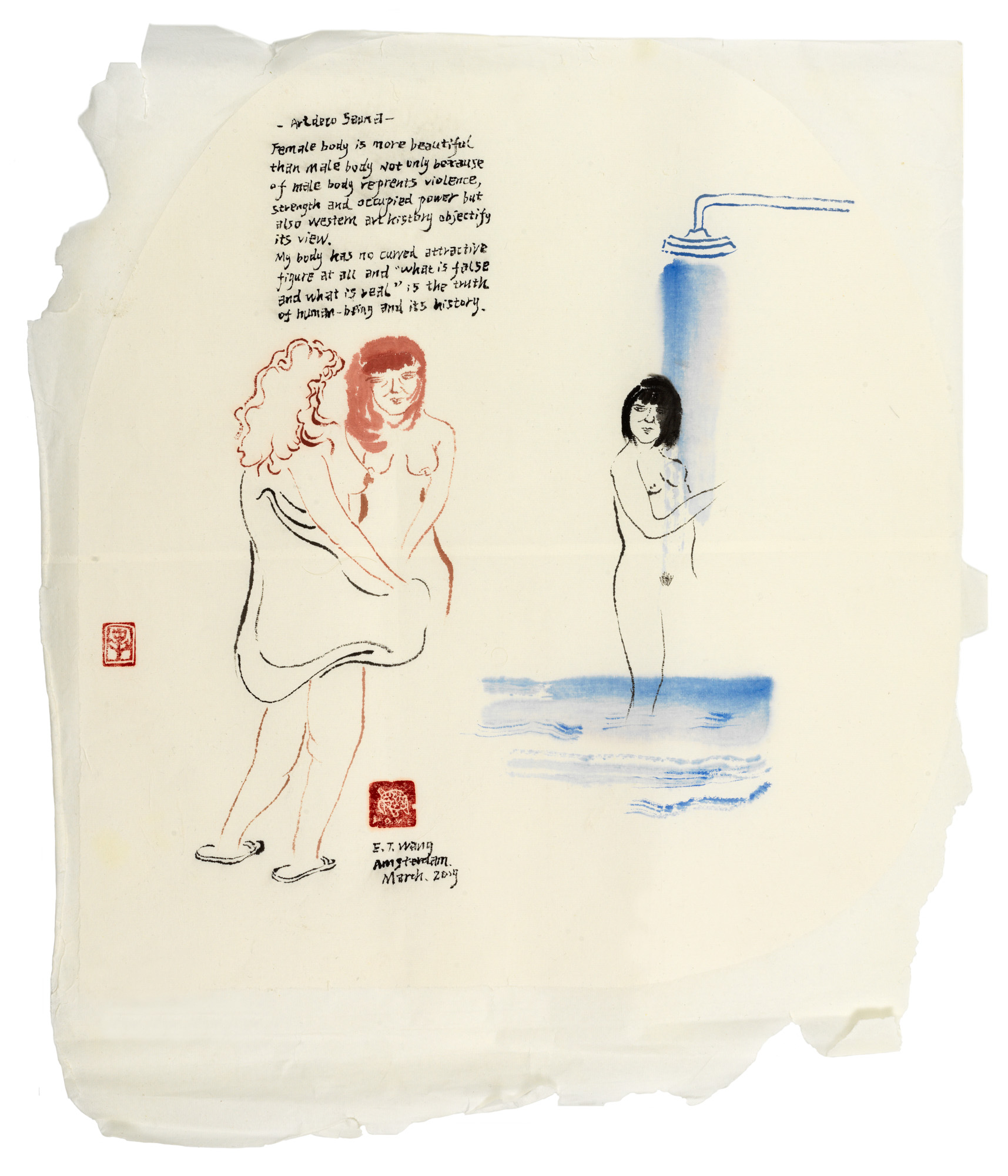

Evelyn introduces me to the clinic’s permanent residents: seven giant pieces of “grandmother” underwear, washed and ironed, and draped across laundry racks. You can wear them as a dress, too; they conveniently cover your head. As Evelyn explains, “Your body becomes exactly an object, which is blind.” She then reads from an adjacent painting, based on a memory from the Artdeco Sauna in Amsterdam, where the granny pants inevitably must come off and the body is no longer “blind”: “Female body is more beautiful than male body not only because male body represents violence, strength, and occupied power but also western art history objectify its view. My body has no curved, attractive figure at all, and ‘what is false and what is real’ is the truth of human-being and its art history.”

Installation view of "Reflection Paper" at the Kunstverein fur die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Dusseldorf, 2021. Photo by Katja Ilner. Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

It seems that a few other guests have recently checked into the clinic as well, old friends and new acquaintances looking for a moment of respite, getting some work done, or just pausing to reflect on “living in the moment of now,” as Evelyn suggests. I see painter Agnes Martin reposing in the center of the space; writer Eileen Chang is hiding in the dark corners of the black box in the back, and luminaries Ingeborg Bachmann and Silvia Federici are spread out on long tables, their stories touched by the cool lighting of the library lamps positioned above them. I am sure the mischievous conceptual artist Ulises Carrión is gossiping in the corner somewhere as well.

Martin, Chang, Bachmann, and Federici join a cast of characters that Evelyn has channeled as avatars in her paintings, performances, and video installations over the last decade. Rather than appropriating the work of these often queer and female authors directly, she chooses a para-fictional approach to citation, using irony, wit, or absurdism as strategies to inhabit the space between her and them. Indeed, in order to stage a perpetual (re)formation of identity through a process of narrative reciprocity, she projects onto these figures her own meditations on body politics, artistic labor, the Kafkaesque bureaucracies of immigration, and language, lots of it: her native Chinese, but also English, German, Japanese, and Dutch, slightly off but always just right,a transformation of words to mean something different—to be lost and found in translation.

Continuing our tour, Evelyn leads me into the garden at the heart of “Reflection Paper,” an intricate scenography of intersecting white walls with circular spaces carved out of the “white icy lacquer,” like Chinese moon gates or Constructivist structures. I look around and find myself surrounded by gridded abstractions in pastel, off-white, and gray shades. These are Evelyn’s reproductions of Martin’s paintings. Some lean against the garden’s arches, others are installed on the surrounding antiseptic walls of the clinic. We sit down on the edge of one of the circles in the wall, among the ruins of modernism, and remain silent for a few minutes. Moments pass before Evelyn describes the canvases as “decorative posters for our clinic” or “children-sized paintings.” They are part of the treatment, a space of reflection and meditation.

Clinic Agnes Martin, OP. 8, 2020, oil and graphite on canvas, 100 × 80 cm. Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/ Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

Evelyn used images from Martin’s Tate Modern retrospective catalogue as source material, reversing the process that the latter artist was so well known for: converting the postage-stamp-sized composition that formed in her head into a sketch that she then scaled up exactly and painted onto a perfectly squared canvas of 183 by 183 centimeters. Evelyn’s intentions appear both ironically melancholic and profoundly sincere, as she transposes Martin’s lifelong quest for beauty and serenity through mathematical precision onto commercially produced, rectangular canvases. As such, Evelyn creates an environment where we can trace the memory of Martin’s vision for beauty and freedom. I look at her with suspicion and she smiles, faintly. She quotes Martin: “I don’t have a friend, and you are one of them.” Once again, Evelyn does not merely copy or imitate: she measures the distance between herself and Martin, and allows us to momentarily inhabit this space. The paintings look like pages out of a book or exhibition posters, each one marked in the corner with Evelyn’s signature red seal along with the number of the catalogue page that she drew from, the size of Martin’s original painting, Evelyn’s own name, and the year of production. They remind me of a poster of Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) on the wall of my childhood bedroom that I used to stare at, having never set foot in a museum at that time. I get lost in memories . . . Evelyn has walked off already, and I follow.

Stills from Reflection Paper I and IV, 2013-14, HD video: 5 min 28 sec and 8 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

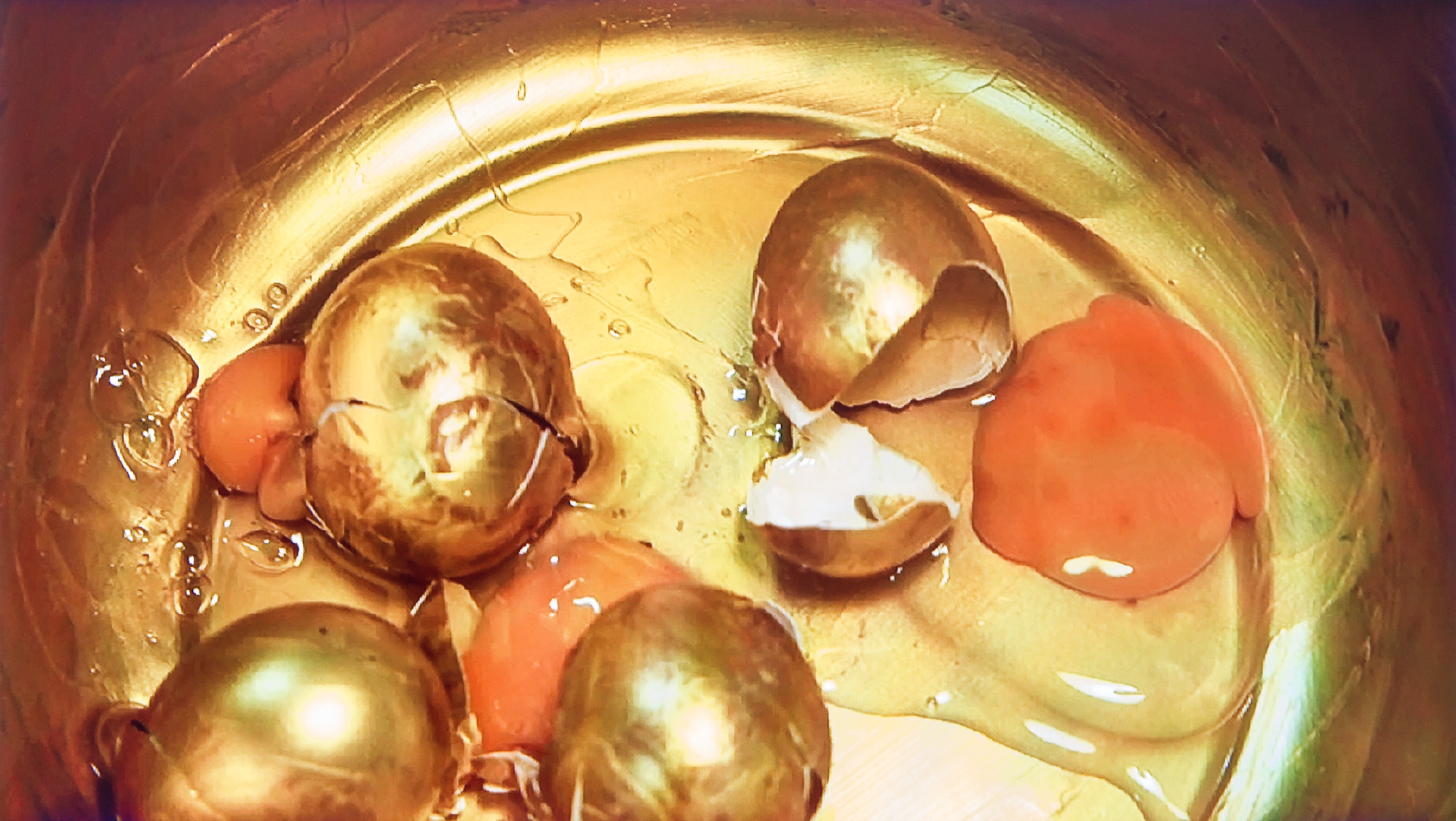

If the garden is the heart of the exhibition, the video series Reflection Paper I-IV is the brain. Created in 2013–14, these videos are visual and linguistic meditations, anchored in the work of literary rebel and solitaire extraordinaire Eileen Chang, who was born in Shanghai and died alone in her apartment in Los Angeles. Quotations from Chang’s literary work appear on the screen and merge with Evelyn’s own language in a high-speed voiceover that sounds both comical and poignant, a stream of consciousness in which she reflects, ponders, worries, and panics about her body, her visa, her art, and her politics. It is hard to say where Chang’s language stops and Evelyn’s voice-over begins: “She wasn’t a bird in a cage, she wasn’t a bird in a cage, she wasn’t a bird in a cage. A bird in a cage, a bird in a cage, a bird in a cage. When the cage is opened, when the cage is opened, when the cage is opened. Can still fly away, can still fly away, can still fly away.” Much of the language is visualized, literally or metaphorically in the videos. There are golden rotten eggs, squashed in a bowl; the decaying corpse of a bird; the rainy surroundings of Amsterdam; excerpts from porn movies; male and female bodies; and color, in all its fugitive abundance. It is strange to see these works again, as they are layered with memories—they were my first connection to Evelyn, and, as with all first loves, they still feel painful and exquisitely frivolous in their melancholic earnestness. Together with another video, Park of Washing Scissors, which Evelyn created with fellow student Colin Whitaker at the Städelschule in Frankfurt in 2011, Reflection Paper I-IV are among the few works that are not produced on the occasion of this exhibition. Rather, they exist as documents that elucidate the arc in Evelyn’s practice, and create another protagonist in the exhibition in the form of the artist as a young man, sharing the stage with Eileen, Agnes, and all the others. If this is a clinic, these videos are regressive psychoanalytical treatment.

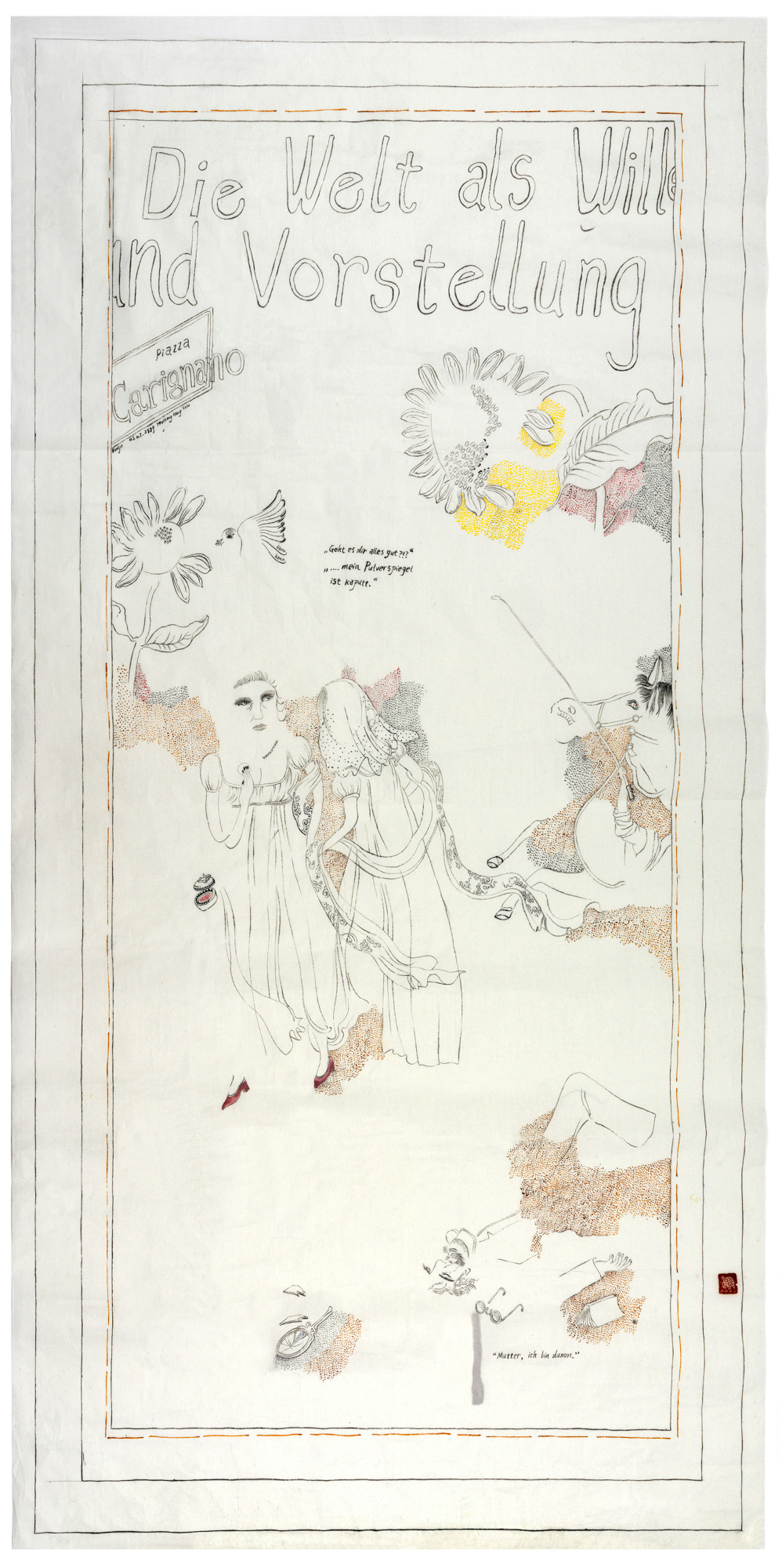

False Poster, 2020, ink, pencil, and water color on paper, 180.5 × 98 cm. Photo by Gert van Rooij. Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

Suddenly, we find ourselves on a crowded street in Turin, Anno Domini 1889. Friedrich Nietzsche is trying to cross the road. Let’s face it, his mental health is already quite fragile at this point. Whispering words to himself about the city’s unparalleled gelato, he is distracted by the sound of lashes, ripping into the flesh of a horse. Meanwhile, mere meters away, Evelyn is out shopping with her girlfriend. Perfume, scarves, shoes, a bonbon—the essentials. They observe the strange-looking man with the moustache as he approaches the horse that is being whipped by its owner. The man falls on his knees and utters, “Mutter, ich bin dumm [Mother, I am stupid],” before he lies down on the street, quietly defeated. Evelyn’s friend asks her: “Are you doing OK?” Evelyn, nailed to the ground as if she has seen a ghost, says in disbelief, “ . . . my compact mirror is broken,” staring at the shards of glass before her. What a day to be in Turin! As we walk past the painting that depicts this auspicious occurrence, Evelyn whispers: “That is why I want that false poster here, because nobody knows if I was really in Turin or not.” Whether or not she was actually in Turin is perhaps best captured in the words at the top of the painting, “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung” [The World as Will and Representation], evoking Arthur Schopenhauer’s 1819 foundational philosophical treatise on the impossibility of knowing the world beyond our subjective cognition.

Sauna, 2020, ink and watercolor on paper, 57 × 48 cm. Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

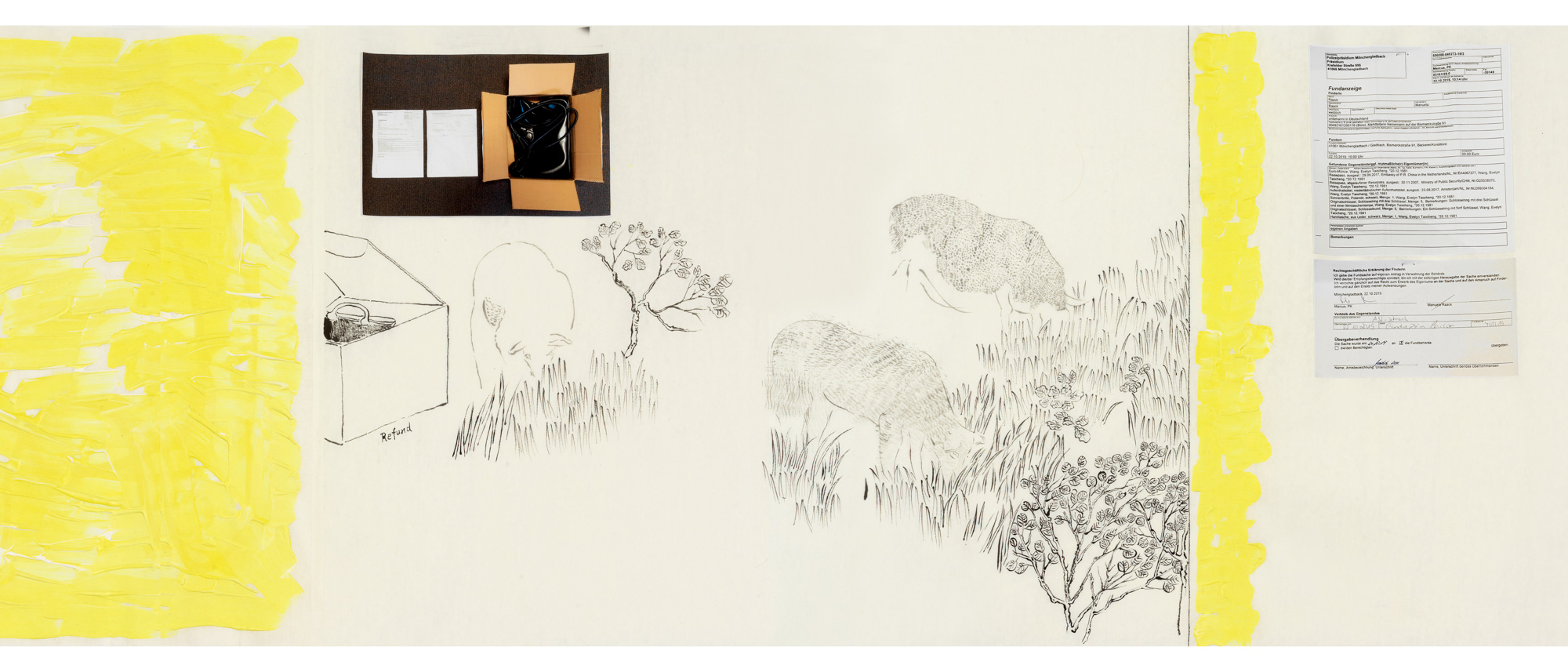

Detail of Booklet of Bachmann – Lost Leather Shoulder Bag Refund, 2020, ink, digital inkjet print, glue, acrylic, and pencil on raw rice paper, 48.7 × 800 cm. Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

One of the most enigmatic writers of 20th-century Austria, Ingeborg Bachmann is the lead character in the large scroll-drawing that Evelyn leads me to next. Bachmann believed that language accumulates meaning through subjectivity and context, rather than a more universalizing principle that would stipulate language means the same thing everywhere, to anyone. On the scroll, Evelyn has transcribed a number of Bachmann’s poems, written in German, and annotated them with her Chinese translations. They do not mean the same thing. On the right side of the scroll, in between the poems, are Barnett Newman-esque fields of color invoking either Abstract Expressionism or Expressionist Abstraction (or maybe neither). Evelyn recalls a story of how, during her 2019 residency in Mönchengladbach, she’d spend time at a cake shop, Konditorei Heinemann—a happy place, where one can sit in granny pants with a Longchamp leather bag, enjoying some Kaffee und Kuchen. The Konditorei had a “library feeling,” a sentiment emulated by the lamps on top of the scroll’s vitrine. But bad things happen in happy places: Evelyn lost her leather bag. Thankfully, it was found and recovered, despite, or because of, the sprawling bureaucracy of German law enforcement. It was returned with a three-page form that Evelyn collaged onto the scroll, next to a picture of the bag in the box that it was sent back in, documenting all the personal belongings in the bag, including Evelyn’s copy of Bachmann’s collected poetry. She contends, “I wanted to give the whole context to create a new kind of understanding together with the poetry.” As I walk by the vitrine, I look at Bachmann’s writing in one language that I kind of understand and another that I cannot read at all, the texts hovering between translation, visualization, and internal dialogue, as language often does in Evelyn’s work. The police form, the photograph of the Longchamp bag, and the colorism of postwar abstraction that has faded to pastels appear as stops on the route that Bachmann’s book has traveled, from Rotterdam to Mönchengladbach, from the cake shop to the hands of a good Samaritan, from one police department to another, from the employee of the lost-and-found department to the doorstep of Evelyn’s host, and back to the cake shop. Was Bachmann quietly reciting her work along the way, seeing how the words resonated in different places?

Screenshot of the artist’s tour of "Reflection Paper." Courtesy Kunstverein fur die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Dusseldorf.

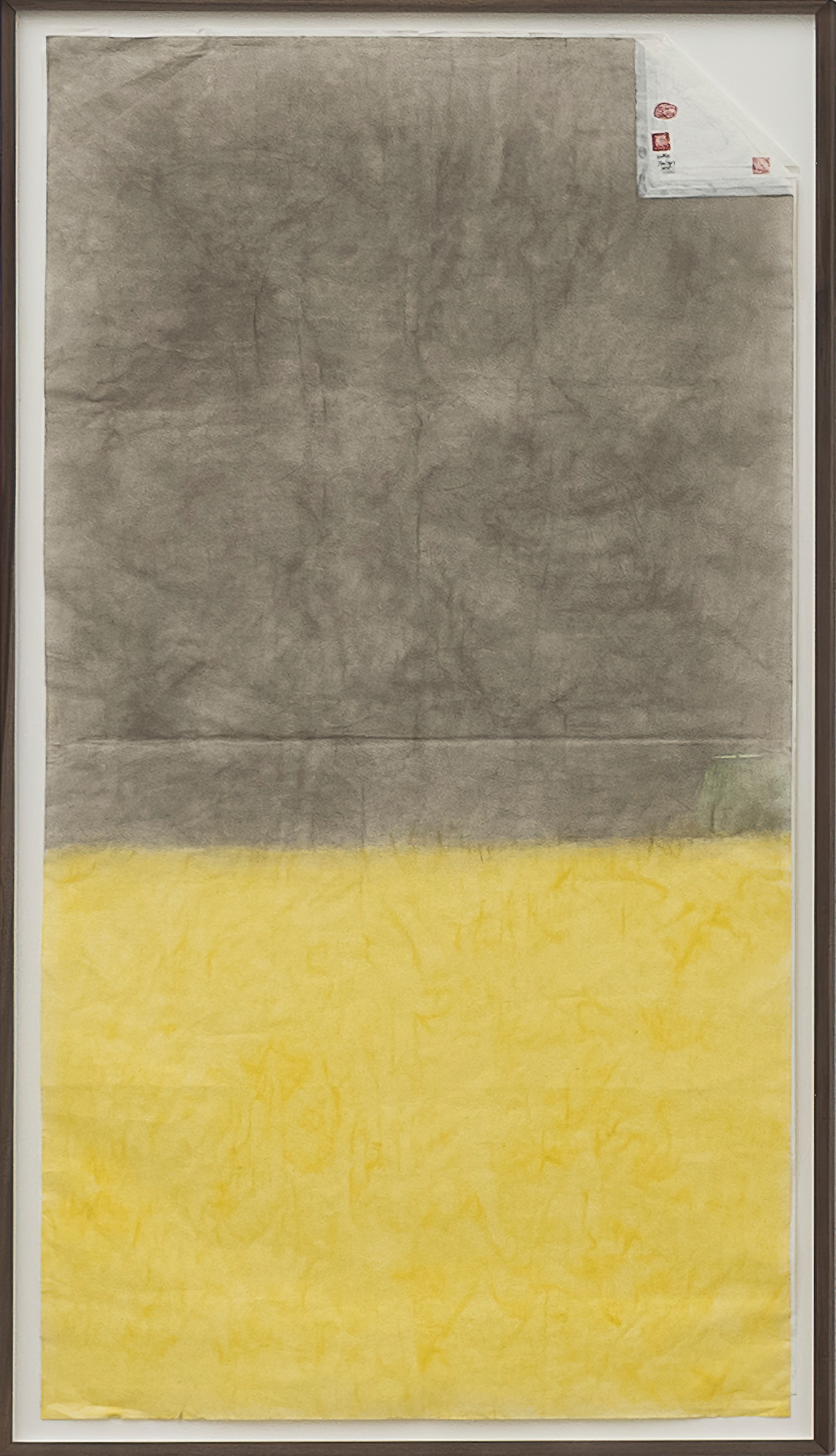

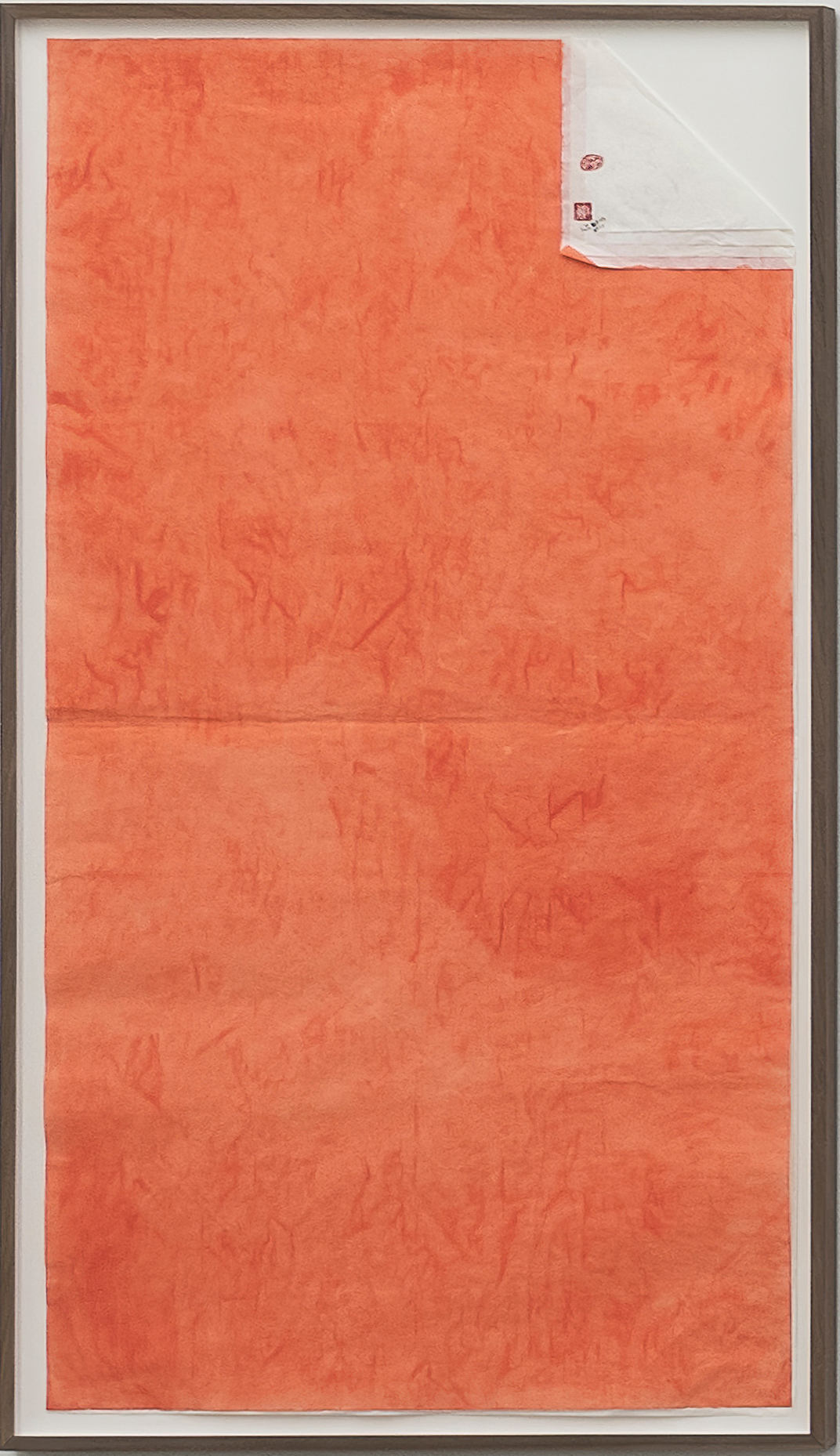

It is time to reapply some rouge, this Rundgang has been a tour de force. We stop at two paintings, one evoking a Mark Rothko-type suspension of yellow and gray color blocks, the other a monochromatic field of coral, a color undecided between red and orange. I am uncertain if I’m looking at an allusion to late modernism, a watered-down version of the German flag, or simply the magnification of an eyeshadow compact, which Evelyn shows off to illustrate her use of yellow. Either way, we’re masquerading. “People will always ask me about my national identity issue, but it’s not about that, it’s just for beauty,” Evelyn says provocatively. Appropriately, we end with a meditation on color, in the form of these two paintings that emerge from a painstaking process of dying layers of fragile paper, conjuring a dialogical relationship between dyes from Evelyn’s childhood and art education on the one hand and the balance between the Apollonian and Dionysian forces that govern our existence on the other. True to the marks of authentication that we see across her work, Evelyn has applied numerous stamps (including one of a turtle) and her signature on the top left of these “eyeshadow certificates.” Her words, “ . . . it’s just for beauty” echo in my mind. Is this what it feels like to put on eyeshadow every day? I should start using it. It’s just for beauty.

I am discharged from the clinic now, having realized that I, too, am fiction—or at the very least, mere representation. Just like Gertrude Abercrombie, I begin drawing a picture of my imaginary selves. A brother perhaps, his name is Anthony. A sister, her name is Evelyn, and Eileen, and Virginia, and Ingeborg, and Agnes, and Ulises, and Silvia. I leave the show and step into my story again.

Color Certificate – Casandra, 2020, mineral color of goose beak yellow (Chinese: e-huang se), Chinese ink, six layers of dye on four layers of ripe rice paper with folded corner as certificate, 183 × 99 cm.

Color Certificate – Minium, 2020, mineral color of minium (Chinese: zha sha se), six layers of dye on four layers of ripe rice paper with folded corner as certificate, 183 × 99 cm. Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; and Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam.

.jpg)