Shows

Zhang Huan and Li Binyuan’s “Land”

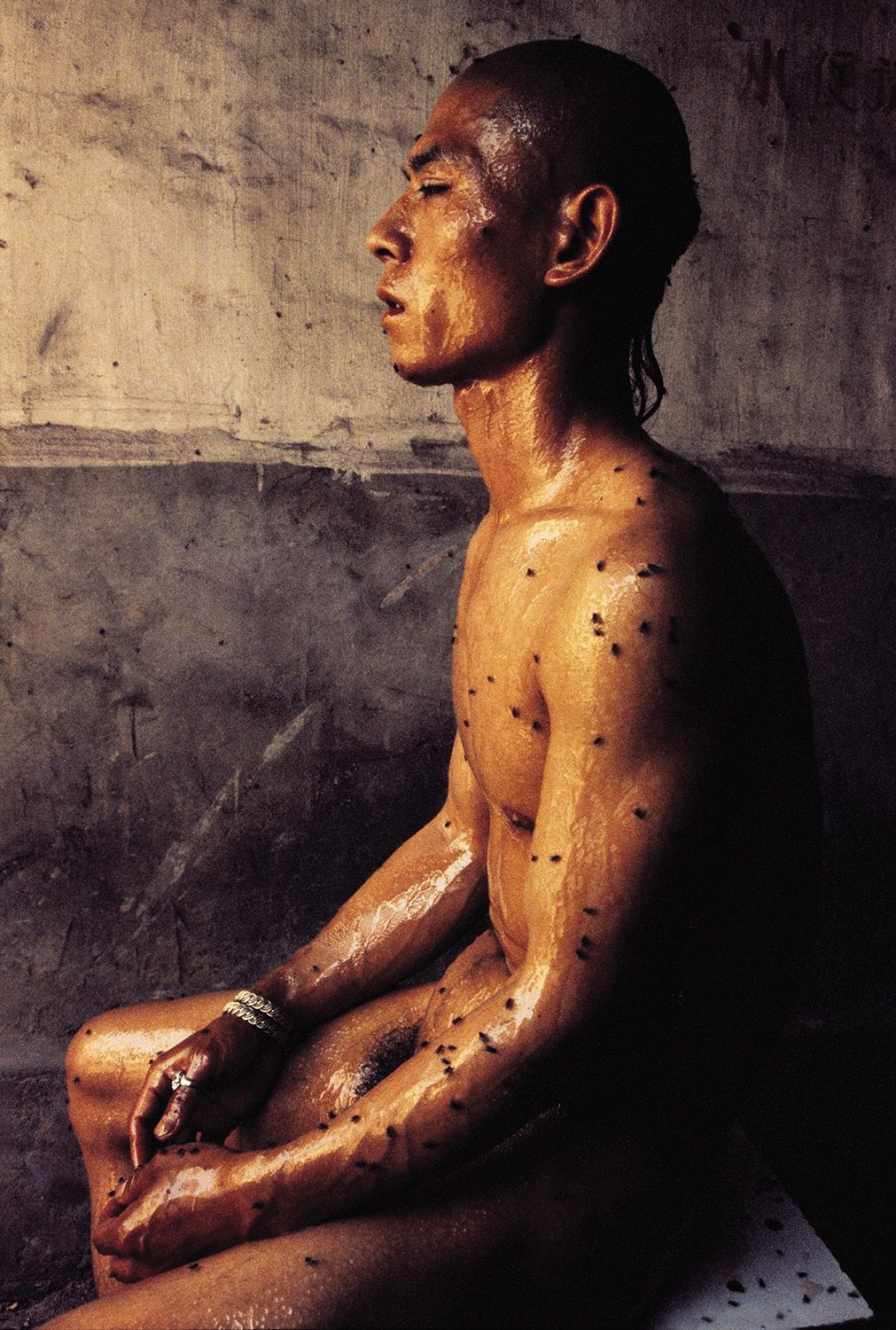

A Certificate of Land issued by the Dahankou Village of Hunan Province hints at the uneasy relationship between individuals and the state over land rights, setting the tone for MoMA PS1’s exhibition “Land: Zhang Huan and Li Binyuan.” A still image of the certificate, which appears at the beginning of Li’s video Freedom Farming (2014), is followed by a two-hour battle between Li and the small plot of land he had inherited from his late father. In the performance, each time Li jumps into a patch of soil in the waterlogged field, the land seems to strike back with splatters of murky water. The pain and nausea he inflicts upon himself are reminiscent of what Zhang forbore in his 40-minute performance 12 Square Meters (1994)—in which he covered himself in fish oil and honey and sat in a 12-square-meter public toilet, attracting flies and other insects—which is captured in a photograph hung on the adjacent wall.

The selection of artists reflected curator Klaus Biesenbach’s efforts to explore the current state of performance art in China, an art form that has seen growing disapproval and censorship from state officials in a country where public space is heavily controlled. Two decades after Zhang’s international debut at this Long Island City institution, “Land” attempted to compare two Chinese performance artists from different generations, and examine how their practices couch social and political critique within the physicality of their acts.

The older artist in this two-person exhibition, Zhang, has become known for his radical yet poetic imagery of the human body. The raw intensity of his work, as seen in To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond (1997), in which he and a group of rural laborers standing in a shallow pond attempt to elevate the water level, communicates the idea of collective struggle, a familiar experience for both artists and the migrant workers Zhang depicts. Departing from the older artist’s solemn and ceremonial performance, Li adopts a dark, wry humor centered on self-ridicule. Known on the Internet as the man who dashed around naked in Beijing carrying a giant crucifix, Li exercises ideas such as precariousness and alienation during a time when individual actions have become highly private, fragmented and inconsistent. In one of his earliest performances, Portraits of Night (2012), Li set up an easel in the middle of a road, attempting to disrupt the flow of traffic; instead of falling into chaos, the cars carefully maneuver past him. By making random encounters and absurd, futile gestures part of his performance, Li expresses a distrust in collective action and experience that Zhang upholds in his work.

Further grounding the connections between the two artists in the historical contexts experienced by their respective generations, Biesenbach framed the show by referencing China’s shifting economic structure and changing ideas of ownership. While appropriately singling out the importance of land in a time of rapid urbanization and privatization, the curator hardly went beyond the titular subject’s literal meaning. For those who have moved away from their native villages, “land” is a symbol of roots, community and, frequently, displacement. Rather than probing these aspects, the exhibition limits the scope of this multifaceted concept by almost exclusively representing land as rural yet idyllic: from Zhang’s collaborative performance pieces staged in the mountains and in a fishpond, to Li’s solo performance in a bamboo grove. This curatorial decision risks endorsing an outdated mode of thinking that exoticizes artwork created by non-Western artists as objects to transport the audience to distant parts of the world. One cannot help but wonder if the portrayal of China as dictated by a Western curator is tailored to the imagination of a primarily Western crowd. While the show included endurance performances intended to provoke, it turned a blind eye toward recent, topical controversies surrounding new land-use regulations and building codes in suburban Beijing that have engendered forced displacement of migrant workers.

The current exhibition prompts those who are aware of the anxiety and discontent surrounding land use to think about how artists have responded to the issue from one generation to the next. For many, however, the whisper of current tensions centered on land in China will hardly survive in the foreign context.

“Land: Zhang Huan and Li Binyuan” is on view at MoMA PS1, New York, until September 3, 2018.