Shows

You’ve Got Mail: Art as Post-Pandemic Letter-Writing

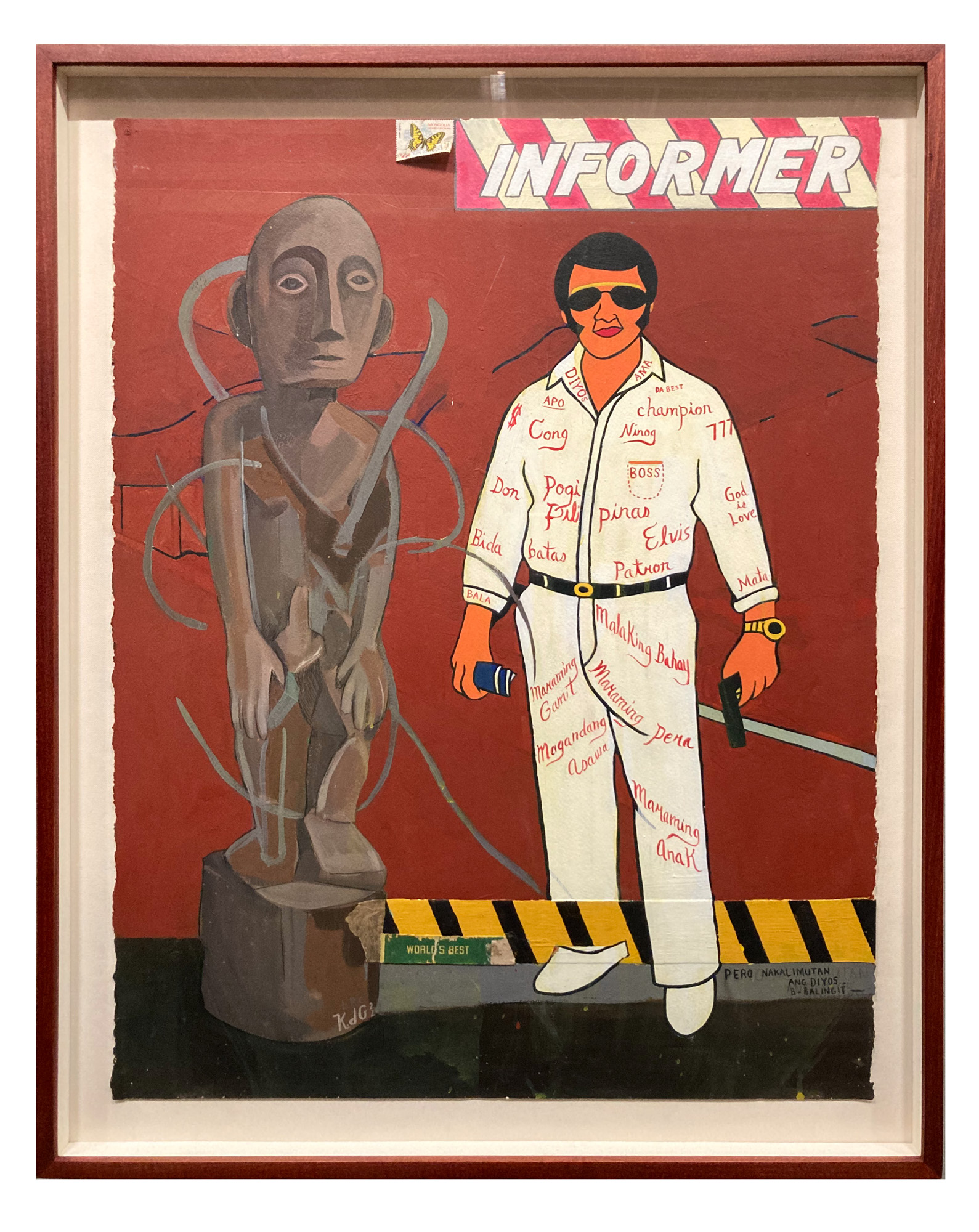

Last October, for the exhibition “Free Phenomenon,” the Drawing Room in Manila had 45 mixed-media collaborations on paper by Kawayan de Guia and Louie Cordero hung in a continuous line around the gallery, hemming the viewers in as they walked the circumference of the space. At a glance, the identically sized and framed works on paper presented a unified whole. However, closer inspection reveals layers of oil, acrylic, and collage cut-outs that bring all sorts of images together, from the quotidian (think cartoon, textbook, and pop culture references) to the profane (decaying skulls, stylized religious icons, and extra-terrestrials).

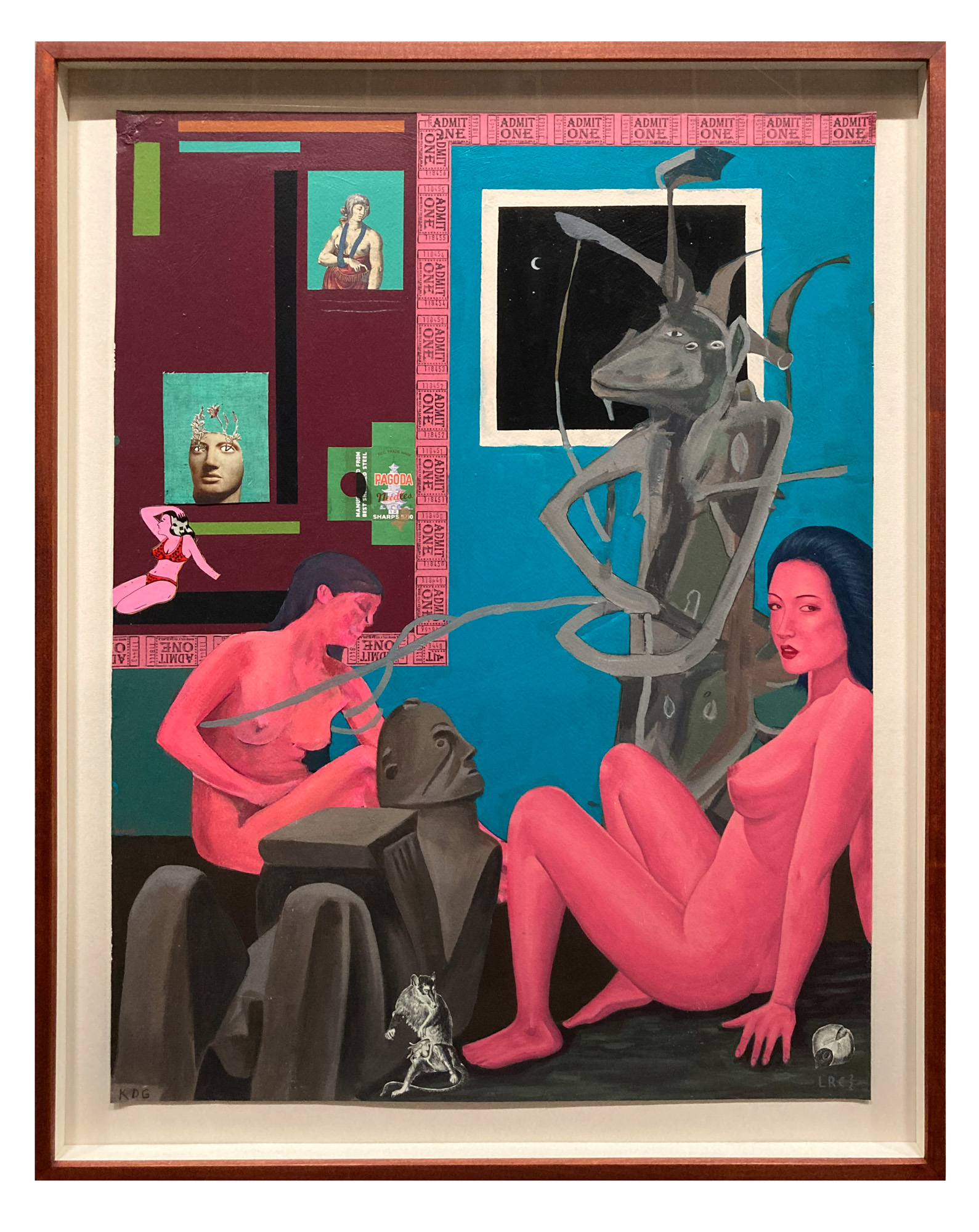

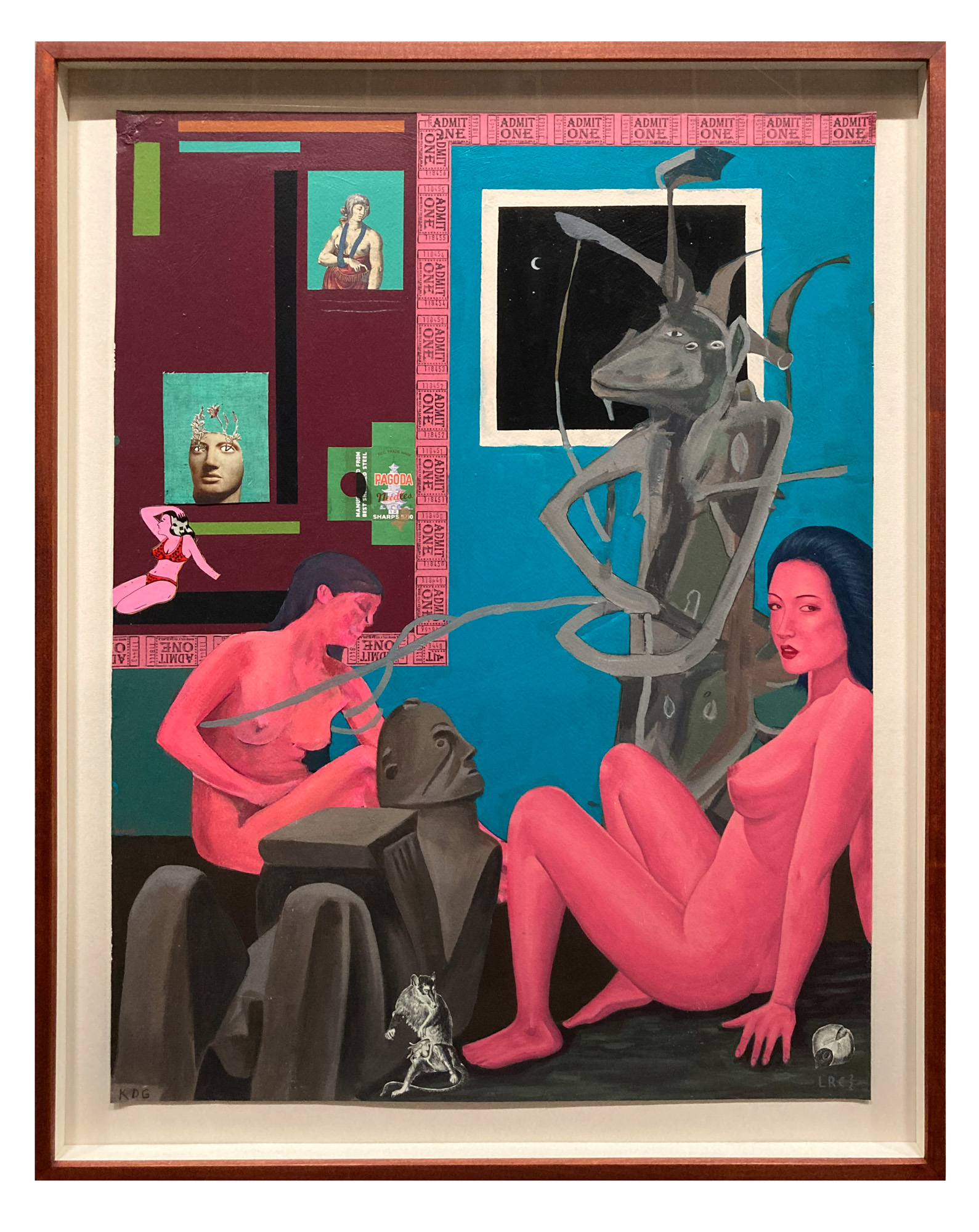

One work titled Free Phenomenon 26 (2022) features two nude women with bright pink skin (one of them even meets your gaze) in a blue room. Between them lounges a bulul—pre-Hispanic rice deity from the Cordillera region—while a tall, insectoid creature occupies the back righthand side of the space, its antenna-like appendages bisecting the room. Cut-outs of pin-up girls and classical sculptures play voyeur and peer into the room through a window with a pane made out of stuck-on “Admit One” tickets. Other collages settle on the level of play, like Free Phenomenon 5 (2022) where a young girl gasps in horror from behind a typewriter, with “Ha! Ha! Ha!” in comic-book font sprawled across the paper in sinister parody.

De Guia and Cordero sent the artworks back and forth between the cities of Baguio, in the northern Cordillera Mountain range, and Batangas, in southern Luzon, where they were respectively based. By the time the show opened, the works had made almost a hundred journeys back and forth over the better part of a year. The wall text described it as an exercise in dialogue, where the painted collages were “formed by distance, circumstance, and need; as well as by [the artists’] own unique artistic vision,” with an emphasis on the act of responding. True enough, each piece feels like it brings a different train of thought to life; they read like paragraphs or sentences in a letter. Cordero would receive pieces from de Guia that were significantly changed since he last saw them and vice versa, the two of them building towards the works’ completion—just like a conversation that had run its natural course after diverging several times from its original idea.

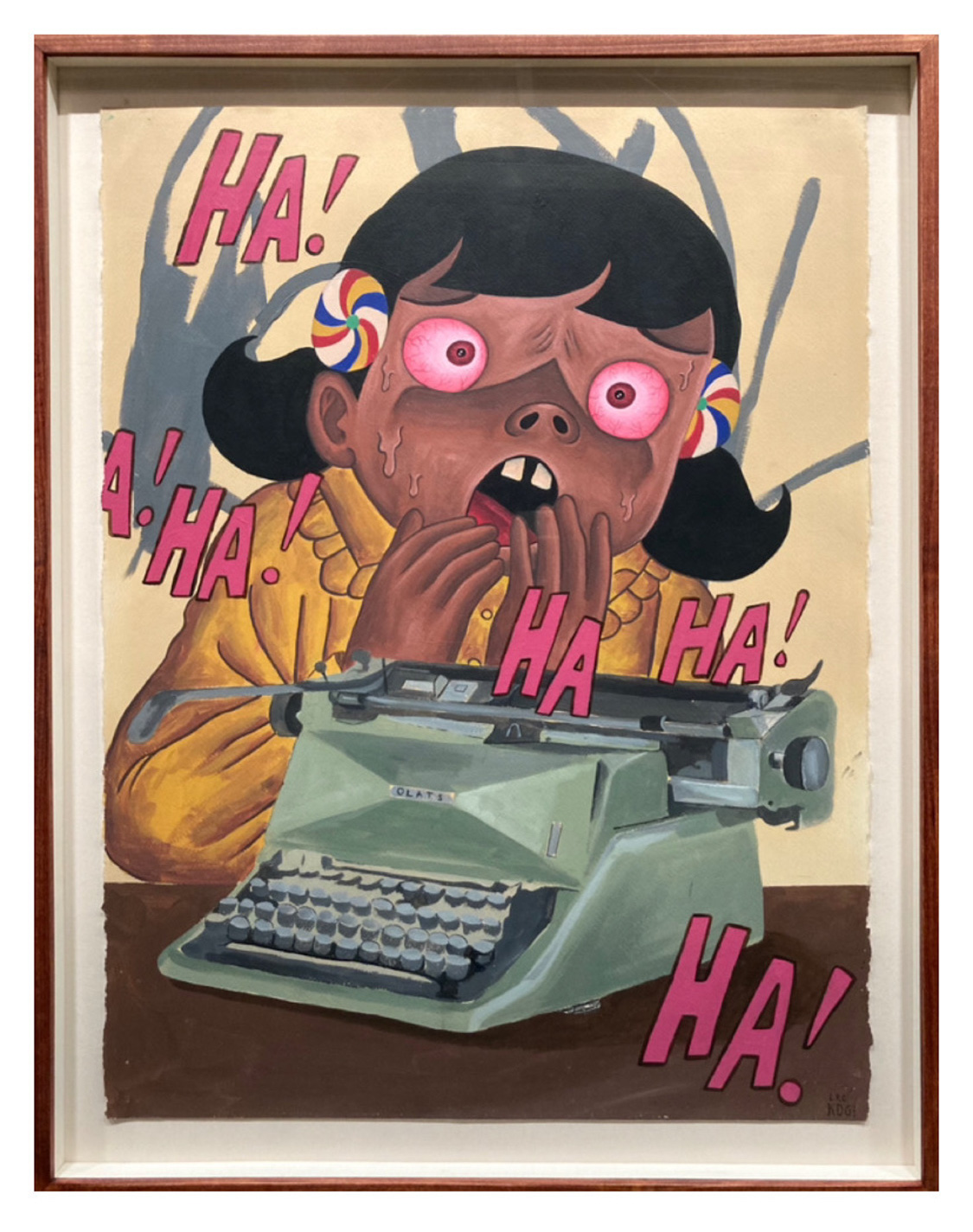

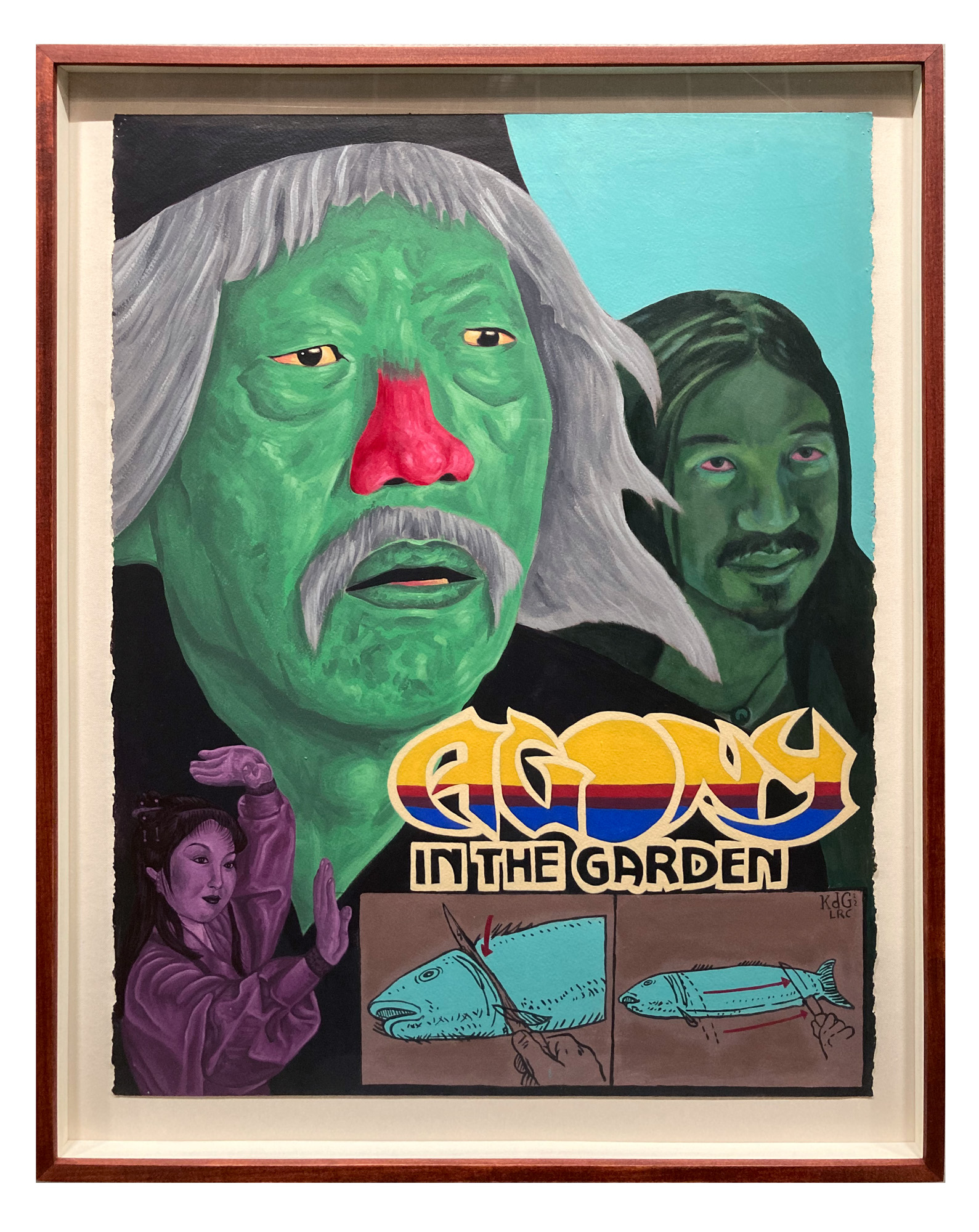

De Guia’s multimedia practice draws heavily on the Indigenous cultures of the Cordillera region. In his two-dimensional works, Ifugao rice gods, Indigenous peoples, and the Pinoy everyman navigate landscapes crowded with Western cultural paraphernalia. While humorous, they ultimately poke fun at the contradictions of a postcolonial society plagued by cultural imperialism and crony capitalism. You may laugh at seeing a wannabe-Elvis standing next to a life-sized bulul—as in Free Phenomenon 9 (2022)—but the words written on his jumpsuit that clash with the gun in his hand will inevitably make you pause: batas (law), malaking bahay (large house), magandang asawa (beautiful wife), maraming pera (lots of money). Where de Guia references the Filipino experience through Indigenous iconography, Cordero has adopted the garish, airbrushed “jeepney art” aesthetic as an entry-point into his local audience’s psyche. Verging on the grotesque, Cordero’s works are a menagerie of figures from local and Western pop culture, folk Catholicism, and trashy Hollywood films. Ultimately, both artists stick their hands in the muddy waters of the Filipino’s cultural identity crisis.

Though this was not the first time the two artists have collaborated, there were noticeable differences between these works and their past efforts. The paintings in “ChaCha Town” (MO_Space, Manila, 2018), their first collaboration, were maximalist in size and composition. Not an inch of white canvas could be found as figures like Ronald McDonald, a zombified Michael Jackson, and colonial-style illustrations stood against saturated backgrounds of varied textures, from sardine-can labels to woven (banig) mats. In contrast, the works in “Free Phenomenon” are smaller in size (most likely for ease of transport), which accounts for the brevity and even restraint in the laying down of images. You get more of a sense of the artists “listening,” as they were forced to wait for the works to arrive before they could respond with a new layer of images. Whereas the works in “ChaCha Town” bear the chaotic energy of two artist-friends embarking on a new project, feeling each other’s styles and processes out, the collages in “Free Phenomenon” are more seamless in the layering of pictures. Figures, objects, and text interact with each other to create mini tableaus.

But it’s not just the physical aspect that accounts for this difference; it’s the intentionality, the timing. De Guia and Cordero embarked on this collaboration amidst a slow return to normal after almost two years of harsh lockdowns in Manila. For de Guia, it was an outlet to grieve the sudden loss of his brother, the artist, photographer, and filmmaker Kidlat de Guia, in early March 2022. For Cordero, it was a way to support a friend, creatively wrestling with de Guia’s grief solidified in paint and paper.

Despite their punchy exterior, the works’ diminished size and pared down aesthetic where images dialogue with each other ultimately lend the show a more pensive air. That perhaps is its largest draw. Socio-political commentary aside, it is a reminder that the lines between those who speak and those who listen, those who create and those who view, aren’t as fixed as we may believe. It’s simply a matter of taking turns: pause, respond, and pause again. Like the pandemic, the show has become a time capsule for this specific interaction between two people, and viewers have been invited to take part. More than the politics, pop-art, and punch lines, it’s the pockets of waiting punctuating the creative process that have been shown to matter, like pauses in a conversation. What use is voicing your ideas when you’re shouting into a void? As we emerge from our physical and digital circles of isolation to re-engage in direct, person-to-person contact, “Free Phenomenon” posed these questions to us: In the age of instant messaging and digital “communication,” how do we step back and listen? How do we allow the other person’s words and actions simmer and settle? And, once we grasp what it is they are saying, what do we do to respond?

“Free Phenomenon” was on view at the Drawing Room, Manila, from October 15 to November 12, 2022.

Monica Fernandez was ArtAsiaPacific’s editorial intern.