Shows

Yoshitomo Nara: “Life is Only One”

What is the meaning of life?

This question may not have a single, definitive answer, yet it is a query with which so many individuals grapple. Among them is Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara, for whom the subject has dominated his body of work for 31 years. Having spearheaded the neo-Pop movement in Japan, Nara’s work is well known worldwide for its depictions of cute yet mischievous cartoon figures. The artist’s meditations on the meaning of life and his perspective on human existence form the basis of “Life is Only One,” his first major solo exhibition in Asia outside of his native Japan, currently held at Asia Society Hong Kong Center.

The exhibition, organized by guest curator Fumio Nanjo, director of Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum, and Asia Society's in-house curator Dominique Chan, presents works that explore the artist’s burgeoning understanding of life’s transience. “When I was a child, the word ‘life’ itself was a foreign concept,” Nara explained in an interview published in the exhibition catalogue. “After turning 50, however, and with the deaths of people close to me and with the recent earthquake, I started to think about life more realistically—the limits of life, and the importance of what one can accomplish during that time.”

“Life is Only One” invites viewers to channel their imaginations and engage in a dialogue with both the work that surrounds them and the wider artistic terrain of Nara’s personal world. The exhibition consists of more than 40 works in five distinct sections that correspond to the mediums in which Nara operates: painting, drawing, photography, mixed-media installation and sculpture.

The first room of the exhibition takes on a gloomy and philosophical feeling with Nara’s popular large-scale paintings. A monumental wood-panel painting from which the exhibition takes its title, Life is Only One! (2007), greets audiences in this first gallery. The work depicts a young girl, eyes alert and deep in thought, clutching a human skull in two hands, surrounded by the phrase, “Life is Only One!” in blood-red text. Drawing from the symbolism attached to skulls and their emblematic links to the inevitability of death, Life is Only One makes allusions to Dutch memento mori paintings from the 16th and 17th centuries and incites emotions of pain, loneliness, helplessness and despair.

Another work, White Night (2006), depicts an overwhelming wide-eyed stare of a girl with a crooked haircut, representative of Nara’s signature motif. A shift away from the artist’s typically bold palette, White Night replaces brash hues with multi-layered brushstrokes of soft oranges, yellows and pale greens. The subject’s eyes in particular—in most other works, portrayed with just two or three solid tones—are here depicted with a range of whimsical shades. Although children and animals are staple subjects throughout Nara’s oeuvre, an stylistic evolution in his work is evident in this piece.

With influences from Japanese anime and manga, the artist’s early works use precise lines to outline the figure of the subject, creating a sharp contrast with the background, both through flatness and color juxtaposition. In these works, the contrast is more subtle and solemn.

If the exhibition as a whole is a tribute to Nara’s entire body of work, the second gallery focuses on changes that have occurred in the artist’s style over time. In 2011, following the catastrophic Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that devastated Japan, Nara found himself in a creative drought, unable to make art. In works such as Wounded (2014), depicting an injured girl with a bandaged eye, and Emergency (2013), portraying a child lying on a hospital bed, Nara’s sense of horror at the damage engulfing his country is conveyed. After returning to his first-ever studio at the Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts and Music, as a residency of sorts working alongside young students, Nara gained new perspective on the kind of art he wished to create and a fresh outlook on his own—and Japan’s—ability to overcome tragedy. At Asia Society, softer lines in pieces such as Black Eyed (2014), Anxiety Days (2015) and Girly Mountain (2011) inject the second room of the exhibition with a welcoming atmosphere, which conveys this optimistic view of rejuvenation. These subjects’ expressions remain open to interpretation, but their lack of spitefulness signifies how Nara’s artistic style and sense of life was effected by the aftermath of the earthquake.

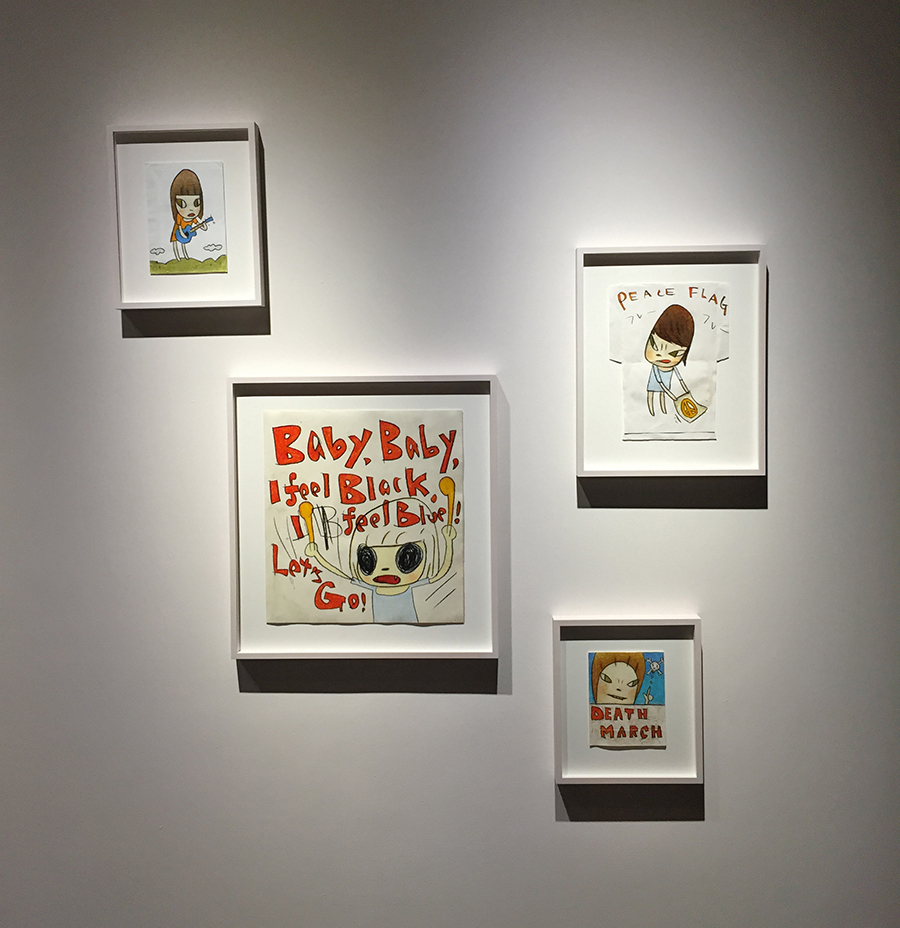

In addition to the artist’s more refined, contemplative paintings, the exhibition devotes a space to his smaller-scale, sometimes fragmentary drawings. Human figures, in their simplest and most honest forms, are drawn onto a variety of different materials, such as cardboard, envelopes and paper, and viewers are invited to look into Nara’s raw sketchbook. It is filled with intimate moments of unfettered creativity. At times overwhelming in comparison to Nara's more nuanced and quieter paintings, his text-based works shout out messages in bold English words, or fine Japanese characters, such as “Baby, Baby, I feel Black. I feel Blue! Let’s Go!” and “I am Right wing. I am Left wing!”

The fourth section of the exhibition gives viewers insight into a less examined area of Nara’s body of work. Photographs taken from his 2014 trip to Sakhalin Island, with photographer Naoki Ishikawa, capture an intimate story of the remote island in the North Pacific Ocean. The former Japanese territory—now Russia’s largest island—had been visited by Nara’s maternal grandfather in the past. The images that line the exhibition walls are perhaps a testament to Nara’s re-envisioning of the island through his own perspective. Photographs depict Nara’s visit to historic Japanese sites across the island, including the Kurei reindeer festival near the Dimauz river, the Otas Forest in Poronaisk, and the former Oji Paper Company, Kawakami coal mine, and Ainu village. With his naturalistic depictions of local people and places, Nara defies misconceptions surrounding the unitary nature of his work and criticisms that they amount to cutesy cartoons. In interviews related to the exhibition, the artist emphasized that the photographs were shot not with an expectation to be viewed by the public, but rather as a reflection of everyday life and its sense and sensibilities.

The final gallery of the exhibition offers a shift both in media and setting with a sculpture entitled The Fountain of Life (2001–13). Depicting three stacked, oscillating children’s heads that seem to be crying tears into the oversized white teacup in which they are held, the sculpture either offers a metaphor for a hard life or a life of joy. Surrounding this sculpture are several fiberglass miniature sculptures of white standing puppies, occupying the perimeter of the room. In the confusing serenity of the space, encircled by glossy white surfaces, viewers are challenged to distance their minds from the imagery of the other exhibition galleries.

Although “Life is Only One” offers no distinctive conclusion about the meaning of life, it lays bare the idea that, for Nara, there is no fixed answer to the question. Maybe, the most meaningful answer is to continue questioning.

Yoshitomo Nara’s “Life is Only One” is on view at Asia Society Hong Kong Center until July 26, 2015.