Shows

Wu Jiaru’s “To the Naiad’s House”

“House of Xiaoxiang (瀟湘館)” is widely known as the residence of Lin Daiyu, the hopelessly romantic heroine in the 18th-century Chinese classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber. But for artist Wu Jiaru, it is the name of a room in her mother’s jau lau (Cantonese restaurant), where she spent most of her childhood. Despite it being translated as “Naiad’s House” in the exhibition’s English title, this personal reference is a point of departure for the artist’s first solo at Flowers Gallery where she showcased motifs, objects, and tales from different cultures, especially those adopted and reappropriated during the late-20th-century reform economy of the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region.

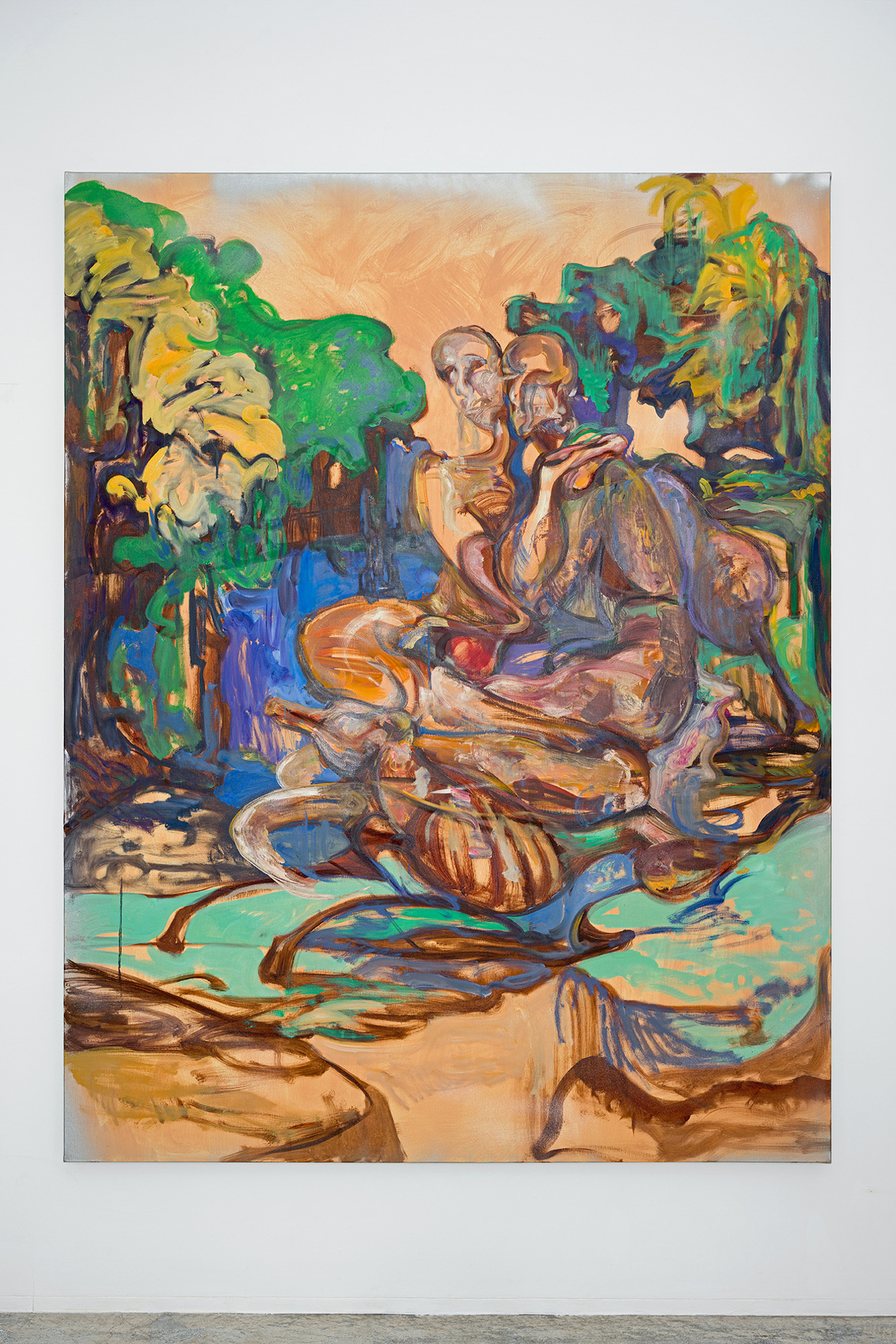

Walking into the gallery, the viewers were greeted by The Creation of Space (2022), a large oil painting that renders two distorted figures in a garden-like landscape against a maroon-colored background. Their postures and intertwined bodies reference a creation myth, perhaps of Chinese and/or Egyptian origins. Looking down, one could spot wheels installed under the canvas and turn it around to discover another painting mounted on the other side. That verso painting, Unknown Tales i (2022), depicts a Sumerian myth, with two panther-like beasts guarding an unnamed female figure near a waterfall—an image that was visually linked to another work fixed on the adjacent wall, Unknown Tales ii (2022), a portrayal of a couple with their flesh melting into each other. Wu connects the two through the bodies of water and greenery that surround the figures, but their identities are obscured. Taken together, Wu bridges stories from seemingly distinctive cultures with brushy strokes, recalling psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s ideas of the collective unconscious and the universality of myths such as paradise.

When one moved the paintings around in the room, one could hear the clacking sounds of decorative plastic spheres hanging off the movable canvases. These items, collected by Wu, were also hidden in a nearby metal cabinet on wheels, which displayed a range of objects from cheap orange soaps and tiger balm, to a white binder that compiles sketches, visa documents, and old family photos with her doodles. Smaller-scale paintings such as a portrait of Kobe Bryant or a reinterpretation of the Tower card in the Rider-Waite tarot deck—each object representing a segment of Wu’s life—can also be found in different drawers. By placing these in a mobile “drawer-archive,” Wu reflects on how no matter where one goes, one inevitably carries the weight of family history, everyday necessities, national or ethnic background, as well as memories of conflicts. But her playfully serious form of presentation, which comes with a pair of white gloves, allowed the viewer to take guilty pleasure in rummaging through the materials of her past.

Further into the gallery were Wu’s more signature new-media works, in which she searches for the connection of visual symbols through objects reflective of the PRD region’s opening up to global influences. Next to the wall she placed one of her amorphous sculptures, from the series beige_objects (2020– ), composed of (what looked like) oversized plastic screws from a kid’s screwdriver set. Coated in a silver paint with its back colored in acrylic and oil, the sculpture serves as her imagination of a future generation that worships these cheap consumer items with a religious sense of purpose. A section of crown molding, commonly seen in the upper-class households and thus widely mass-produced in China, was placed on the ground, instead of connecting the ceiling and the wall. These paradoxical arrangements of the cheap and the refined, the mundane and the spiritual, examine the popular aesthetics widely adopted by people pursuing a prosperous lifestyle and greater social status.

With echoes of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927) in the title of her exhibition, Wu suggests that a room—and specifically, the one in her mother’s restaurant, which now exists only in her memory—can symbolize a place of longing. The entire show was filled with visual elements that seemed vaguely familiar or nostalgic to me—and perhaps others who witnessed the development of PRD from the late 1990s to the early 2000s—but I can’t quite pinpoint them in my memory palace. The sense of elusiveness throughout the show accentuates this rootless state, without wrestling with the idea of a singular “origin.” As much as the show appeared to be Wu’s archive of personal history, it connected with the universal hopes and fears we all have during the transitional periods in both our lives and society.

Wu Jiaru’s “To the Naiad’s House” was on view at Flowers Gallery, Hong Kong, through November 12.