Shows

Weng Fen’s “The Vanishing Landscape”

Part of Capture Photography Festival 2022, Weng Fen’s solo exhibition “The Vanishing Landscape” was presented in Canton-sardine gallery in Vancouver’s Chinatown, a hub for diverse cultures and arts. On view were two parallel series, including The Vanishing Landscape (2021), which depicts places in Hainan where not only the natural landscapes but also the fundamental social-justice systems and careful land management have been compromised. China’s southernmost province, Hainan has ten cities and ten counties that are home to diverse ethnic groups and indigenous languages. Since 1988, Hainan has been a Special Economic Zone, and in 2020, plans were rolled out to transform it into a free-trade port by 2025. Though The Vanishing Landscape did not explicitly place blame on any single party, texts on the walls—such as “Our preserve land has no irrigation water, while the agricultural company rented our fertile land without completing the payment”—pointed to short-sighted economic development, mismanagement, and corruption as explanations for the utter disregard for the richness of the natural land. These statements resonate with me not only because of the prevalence of such issues in China but also in colonial Canada, and no doubt are shared concerns in other places of the world.

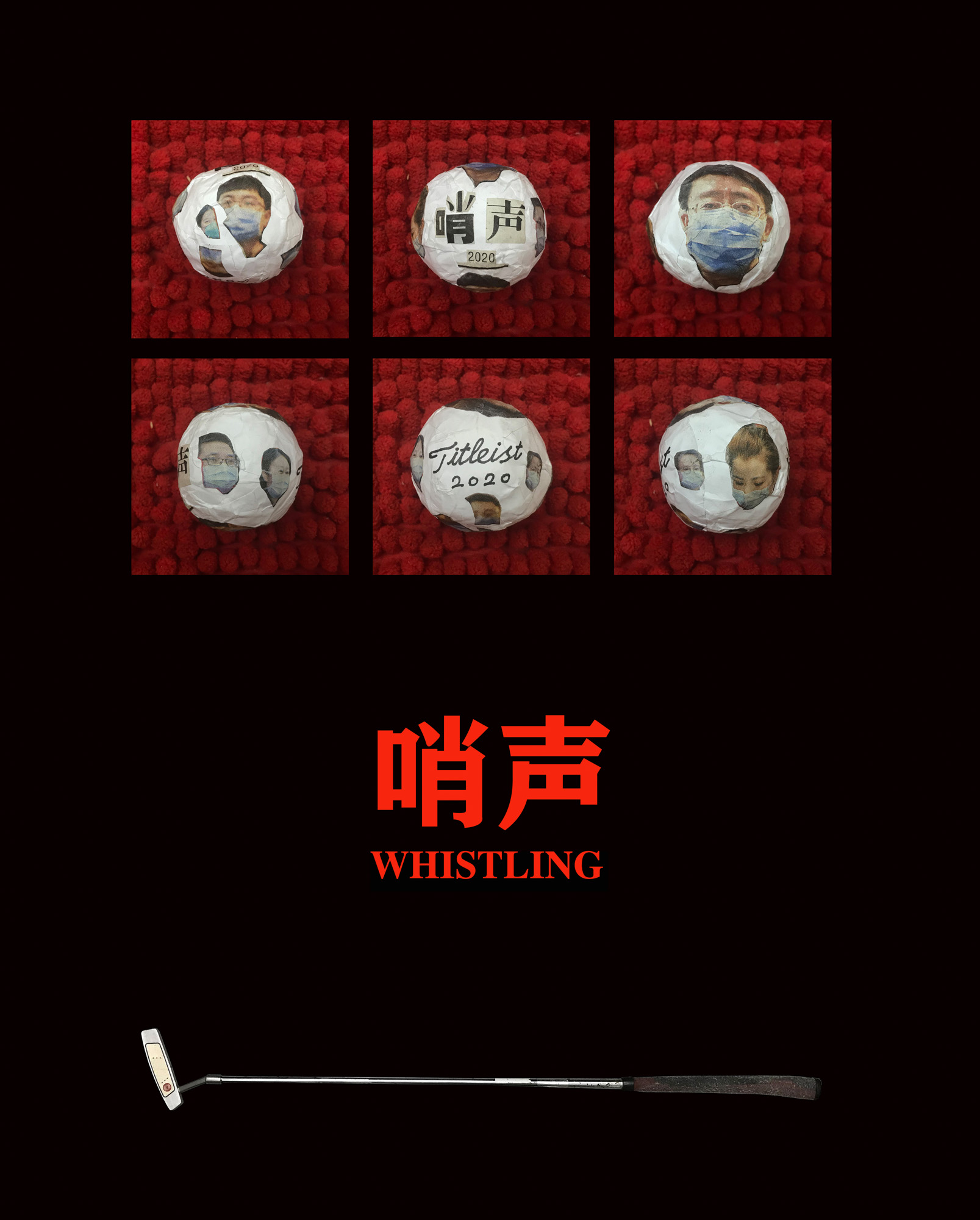

The images from The Vanishing Landscapes, featuring dried-out plots of dirt, concrete structures juxtaposed with pockets of greenery, and the backs of local residents, served as the scenery for the mini-golf course installed in the gallery as part of the show’s other series, Learning to live better in this world (2021). Made during the Covid-19 pandemic, the golf balls are composed of paper with printed images and slogans created by the artist, and portraits of people and global politicians. Visitors could put the balls within the confined area of the gallery’s grass-carpeted lower level, activating the metaphor for the limits placed over information entering and exiting China during the pandemic and the country’s draconian lockdowns. In contrast, visitors could adopt by donation and disseminate copies of the brightly colored posters that feature close-ups of 20 different golf balls, where the six surfaces of each ball are represented by each poster; in turn, these posters are used to tile the walls on the gallery’s upper floor, with captions such as “WUHAN LIFTS BLOCKADE,” “Incubation Period,” and “NO HUG.” The impact of this series was enhanced by a video on a small screen, repeatedly showing someone putting in a different location within the same domestic space. The footage evoked a Covid-era lockdown joke: “Where are you thinking of spending your vacation? Your bedroom or your living room?” Subtly hinting at the tensions between notions of growth and restriction in modern China, the poignant placement and pairing of the two series indicated that the exhibition’s two curators, Steven Dragonn and Xiaoyan Yang, have a profound understanding of Weng’s art in the context of the sociopolitical realities of the country.

China’s development in the 21st century is likewise the focus of the photographic series that earned Weng prominence, titled Sitting on the Wall (2001– ). This earlier group of works features the backs of individuals perched on walls, looking out on the drastically changing landscape of Chinese cities, and has become a representative depiction of China's modernization. Within Sitting on the Wall, Hainan serves as a real example of modernization but also as a caricature that condenses the madness and extremity of how China has sought speedy economic growth. The relevance of this series is so much so that selected works are in the permanent collections of institutions such as the Centre Pompidou (Paris), the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), the National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne), and M+ (Hong Kong).

It was at a time when his urban photography was enjoying great international success that Weng returned from Beijing to his hometown of Hainan, and, since 2007, his practice has been centered on Hainan's villages. In contrast with modern ways of drastically changing physical spaces, he focuses on the restoration and reconstruction of rural homes and ancestral halls, exploring not only the relationships between the island's unique cultural traditions, but that between the people, the land, and the sea. For Weng’s renewed rural settlements, he advocates the concept of “village art, nature living.” By bringing villagers together to work on reconstruction projects and encouraging dialogues between them, he also promotes a mindset of cooperation and tolerance among residents of diverse cultural backgrounds, incubating benign social relationships in the long term. Thus, The Vanishing Landscape lives not only on the walls of art galleries but in the hearts of the people who in turn are empowered to shape how “progress” may look and to tackle the problems of urbanization. With economic development, especially when there is a top-down governmental approach, the uniqueness of environments and cultures are often sacrificed and homogenized. The future of Hainan requires respect for the peoples’ complex identities and their connections to their environment and ancestors—not unlike how Indigenous peoples in Canada would appreciate it.

While The Vanishing Landscape visually captures the conditions of Hainan, I am left wanting to see more of other places in China yet wishing that less of civilization is vanishing. And while Learning to live better reveals the psychological toll that draconian confinement-measures took from Weng, it also brought a sense of humour to the show. Ultimately, I was grateful for the opportunity to see the works of such an influential artist in Vancouver, as well as for the moment to contemplate what is really progressing within humanity and the role of artists in shaping culture and society.

Weng Fen’s “The Vanishing Landscape” was on view at Canton-sardine, Vancouver, from April 9 to June 4, 2022.