Shows

Wael Shawky’s “Larvae Channel”

There are just two film works, each under 15 minutes long, in Wael Shawky’s solo exhibition “Larvae Channel,” at the Delfina Foundation, on display as part of the “Shubbak Festival: A Window on Contemporary Arab Culture” in London.

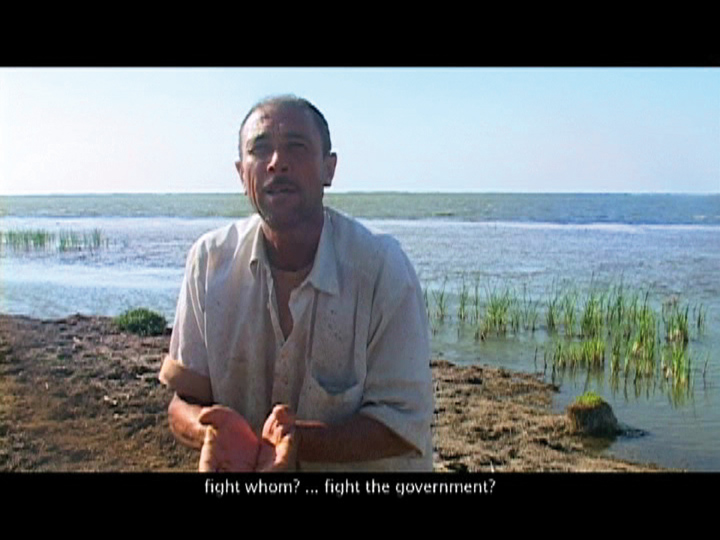

Larvae Channel (2008), shown in split screen format, is a montage of various footage shot in and around rural and fishing villages across northern Egypt. The audio jumps between the screens, following the voices of local residents as they describe the impoverished circumstances of their professional and personal lives. It is impossible to follow one story without the intrusion of another from across the double screen. At one point the angry words of a teenager—“This country humiliates us . . . I want these words to reach the authorities”—collide chaotically with an elderly father explaining the loss of his home: “Please help us find a place to live.” It is these direct appeals to the camera that reveal Shawky’s interest in investigating how the medium can bear witness to the kind of devastating socio-economic circumstances that, in this case, preceded a revolution sparked in the country’s capital three years after this film was made.

Larvae Channel 2 (2009), employs an animation technique whereby each frame is etched over with drawings: as an elderly Palestinian couple describe their forced removal from their home in the West Bank, a cartoon-like outline around the pair accentuates their every move and gesture. While Larvae Channel has an enveloping effect, inviting the viewers to do their own editing (and interpreting) of the overlapping stories, Shawky’s intervention in Larvae Channel 2 unceasingly makes the viewer aware of their role as an outsider—forever a spectator to a process of mediation. The intention behind Larvae Channel 2’s labor-intensive technique, as stated by Shawky in an artist talk at the Delfina Foundation in April 2011, was to inscribe the hardships of the couple’s everyday life onto the film’s material form. While this solution to the problem of representation is completely in vain, together the two films offer an honest inquiry into the possible ways that the camera can act as an agent of testimony.

The exhibition marks a turning point in the artist’s practice, which is characterized by larger-scale film productions and the use of exhibition space as a locus for the interplay of drawing, painting, puppetry, installation, performance, sculpture and film. Shawky has previously characterized his method as “translation,” whereby the artist is a kind of mitigator sourcing a visual language to communicate complex ideas. The “Larvae Channel” series, with its move towards a documentary aesthetic, is the artist’s exploration of his alternative, creative identity as an “instigator.” Shawky’s decision to open up his private studio in Alexandria as a learning space for younger artists perhaps best reflects this shift: that while the artwork can communicate and denounce ideas, art-making as an activity should gather people and ideas, in order to become a catalyst in itself for political change. This leaves Shawky open to the kind of criticisms that are targeted toward “political” artists, whose practices are often plagued by the as-yet-unanswered question: can art and agency ever be reconciled in the same (gallery) space?