Shows

“Vision of Nature: Lost & Found in Asian Contemporary Art”

“Vision of Nature: Lost & Found in Asian Contemporary Art,” co-curated by Connie Lam and Mori Art Museum director Fumio Nanjo, has been one of the highlights of the Hong Kong Arts Centre's (HKAC) exhibition line up for 2011. Part of HKAC’s third annual guest curator program, “Vision of Nature” invites audiences to uncover forgotten aspects of the traditional Asian concept of nature and to reconnect with this through contemporary works by eight celebrated artists from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and China.

Takashi Kuribayashi, from Japan, and Lam Tung-pang, from Hong Kong, take their inspiration from the theme of the forest. Kuribayashi creates a white forest wonderland using traditional papier-mâché in his work Wald aus Wald (Forest from Forest) (2011). With this, he asks the audience to rethink what constitutes a natural landscape. The paper in a book, for example, is easily dismissed as a synthetic object, but within a paper landscape, it takes on the quality of a living environment. Forest from Forest revitalizes the holistic concept of nature—which includes the man-made world—shared in the philosophical heritage of East Asia (Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism). Parts of the installation are also intentionally hidden from the audience and unveiled as viewers peer through holes, which dot various levels of the gallery-spanning terrain, to see different parts of the forest. In one sense, the experience is not unlike viewing a scroll painting—the totality of which can never be viewed at once.

In Past Continuous Tense (2011), Lam Tung-pang uses unconventional media to tackle a seldom explored subject in Chinese ink painting: the forest fire. With charcoal on plywood, Lam depicts a forest blaze, with collapsing trees, by combining rubbing, erasure and burning to allude to humanity's destruction of the natural environment. While the seasonal cycle of nature is a recurrent theme in traditional Chinese painting, the ruined landscape can symbolize war, human resilience to natural disaster and nature’s ability to regenerate. While refusing to be labeled a traditional artist, Lam references centuries old East Asian painting traditions, sourcing images of trees from Korean, Japanese and Chinese painting manuals dating from the 10th century to the present—to illustrate the ever relevant, equivocal relationship between humans and nature.

The conceptual work of Pak Sheung-chuen, another Hong Kong artist, critiques the loss of sensitivity and responsibility toward our surroundings. As a means of personally recovering this lost sensibility, Pak embarked on the journal project 2011.7.27 – 2011.11.14 (2011), jotting down sentences of inspiration that flashed through his mind as he wandered around the city. Out of the 400 ideas he noted over a period of three months, some 30 sentences were selected for this exhibition -- the rest have been compiled in a book. One reads, “Give yourself fewer choices, spend less money, slow down your life. Such backwardness is a progressive alternative.” Pak’s solutions to urban living are reminiscent of the ideals of the traditional literati way of life—such as the classic Chinese novel Xianqing ouji (“Random Jottings of My Leisurely Mood”) (1671) by Li Yu, which describes the aesthetic thoughts and idle character of a cultivated Chinese gentleman.

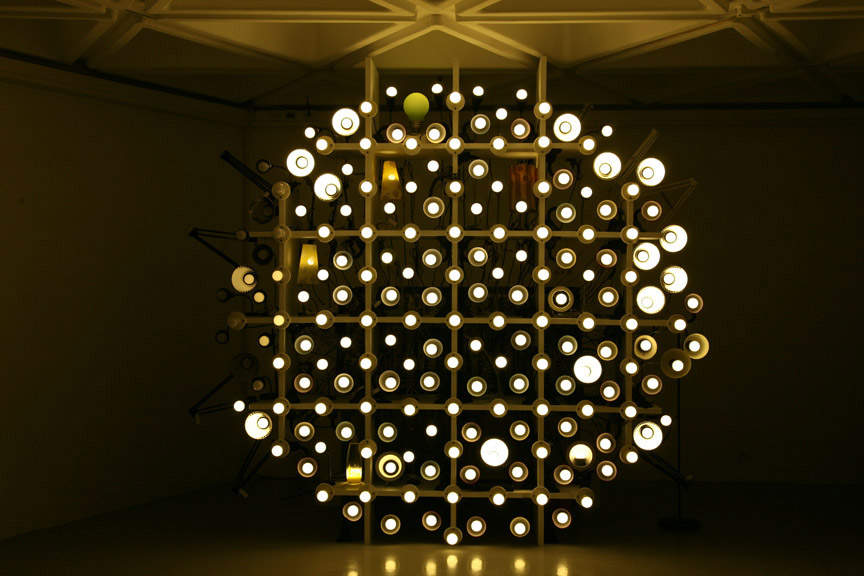

The Taiwanese art collective LuxuryLogico’s conscientious installation, Solar (2011), incorporates more then a hundred unwanted lamps, which are refitted with LED light bulbs, into the figurative shape of the sun. In a darkened room, the lights flicker and shine in different patterns and intensities to create an ambiance of something akin to satellites blinking in outer space. Solar is an attempt to make the audience rethink the necessity of consumption. While modern conservation rather than tradition features in this work, nevertheless its call for environmental responsibility could signal the loss of an ancient awareness of nature to urban development.

Allusions to traditional subject matter in some of the exhibited works invite questions about how old modes of thinking about nature have carried over to a contemporary context in an urban environment such as Hong Kong. The interrelationships between East Asian aesthetic traditions and universal artistic values have great potential for further exploration. While a less symbolic, more direct critique of people's reckless ambivalence toward nature is yet to be seen, this refreshing exhibition aptly introduces new sensitivities, concepts and visions of art on nature.