Shows

Vernon Ah Kee’s “Not An Animal or a Plant”

Conceptual artist Vernon Ah Kee’s first solo show in Sydney since 2008 consists of key works from his decade-long practice. Entitled “Not An Animal or a Plant,” the show includes drawings, paintings, text-based work and custom-made surfboards, all of which have become familiar tropes in his oeuvre. The exhibition is part of this year’s Sydney Festival (1/7–29) and is certainly the event’s feature program being set across two floors of the National Art School Gallery.

Vernon Ah Kee—born in 1967—is a member of the Yidindji, Kuku Yalandji, Waanji, Koko Berrin and Guga Yimithirr peoples and since his inclusion in the 2008 Biennale of Sydney, where he showed a dozen or so oversized portrait drawings of family members to great acclaim, has gone on to participate in the Istanbul Biennial (2015), and the International Quinquennial of New Indigenous Art at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in 2013.

“Not An Animal or a Plant” marks the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Australian Referendum determining whether indigenous Australians should be included in the national census. The Referendum did not give indigenous Australian citizenship rights and did not include them in the Australian Constitution, although many of the 90 percent of voters who casted their ballots in favor of the Referendum erroneously thought that this was the case. Ah Kee was born in Queensland the same year as the Referendum.

Ah Kee is nothing if not a politically-charged artist and in these works he pulls no punches delivering the message of how his people have suffered, and continue to suffer, racial prejudice, discrimination and racial inequality, with an acerbic directness. For a largely white audience, Ah Kee’s oversized acrylic, charcoal and crayon portrait drawings on gray canvas, mainly of family and friends, can be a humiliating and confrontational experience. Several of his works are inspired by black-and-white photographs taken by anthropologist and entomologist Norman Tindale dating back to the 1930s to 1960s. Tindale mapped the various tribal groupings of indigenous people, which led him to question the accepted theory that they were largely nomadic. As the Australian indigenous artist Jonathan Jones successfully pointed out with his recent Kaldor Public Art Project installation, Barrangal Dyara (Skin and Bones) (2016), indigenous Australians have a history of cultivating vast areas of land dating back thousands of years. Bread-making instruments have been found indicating indigenous groups cultivated crops—they were not nomadic. But where Tindale’s assertions were correct, his classification fell short in his enthusiasm to classify his subjects as objects—he identified his subjects by number—a procedure that overrode their inherent dignity.

One example of Ah Kee’s appropriation of Tindale’s photographs is seen in George Sibley (2008), who was Ah Kee’s great-grandfather. The artist’s highly-realistic style allows him to reclaim the sterile image and add a layer of emotional intensity. The primarily caustic purpose of his drawings is often obscured by Ah Kee’s exquisite execution. Whether he likes it or not, his drawings, with their vigorous staccato lines and abstract cross-hatching, possess a lineage that stretches back to Renaissance times and tips their hats to Rembrandt on the way.

It is this objectification of his ancestors both familial and spiritual that Ah Kee so successfully articulates in these portrait drawings while conveying a startling humanistic depth with a chilling directness. We the audience are seen by these staring eyes as the colonizers. It becomes a disturbing truth but one that is difficult to avoid.

Ah Kee continues to tackle contemporary indigenous issues and the one that has preoccupied him for over a decade is the 2004 death of Cameron Doomadgee on Palm Island, an island off Queensland once a Government Aboriginal settlement. Doomadgee’s death under police custody led to riots on the island. Lex Wotton a local Aboriginal elder was accused and subsequently jailed for nearly 2 years in 2008 for inciting the riot. There are two portraits of Wotton in Ah Kee’s current exhibition, one of which is I See Deadly People, Lex Wotton (2012). The large painted portrait is adorned with white lozenges resembling fierce paint-like tribal markings. Similar to Ah Kee’s drawings, the subject’s eyes in this painting are equally confronting.

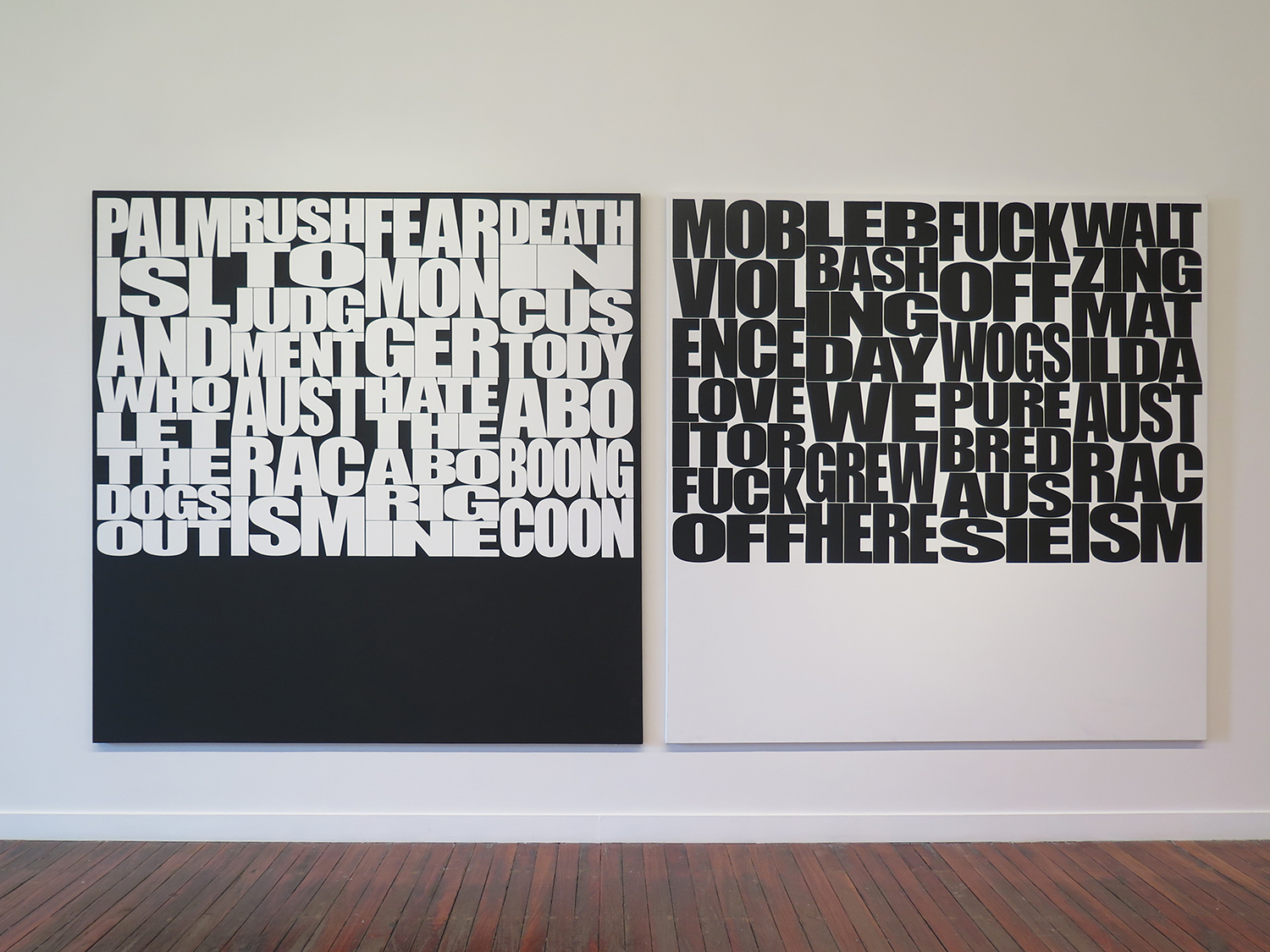

Text was the primary medium that established Ah Kee’s reputation and remains a strong trope in his work today. Two of the most sophisticated pieces in the exhibition are text works, Rush to Judgement (2016) and Waltzing Matilda (2016), ironic, bold and pithy statements on large black-and-white panels. Where Rush to Judgement delivers Ah Kee’s continuing polemic on the plight of indigenous Australians, Waltzing Matilda broadens his racial constituency to include Lebanese and Italian migrants to Australia. Difficult at first to comprehend because of the dense juxtaposition of blocks of large type and their kerning, closer examination delivers an accusatory slap in the face for the viewer as Ah Kee’s uncompromising message hits home. Born in this skin (2008) is a text piece on show here and is a powerful statement of the issues that are at the forefront in Ah Kee’s thoughts on identity, nationhood and prejudice. The work includes the phrase: “everyday/iachievesomething/becauseiwas/borninthisskin/everyday/iconcedesomething/becauseiwas/borninthisskin.”

As Ah Kee told me previously, “If you need to send out a message, then you must make sure it is clear.” And from this exhibition, his message is simple: he asks that basic human decency be extended to all indigenous Australians. I would like to think that “Not An Animal or Plant” moves in a direction toward this, but I fear Ah Kee will be fighting for many years to come.

Vernon Ah Kee's “Not An Animal or a Plant” is on view at National Art School Gallery, Sydney, until March 11, 2017.