Shows

Up Close: Eroticism in the Works of Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki

“Women? Well, they are gods. They will always fascinate me,” remarked Nobuyoshi Araki. Quoted innumerable times, the origins of Araki’s words seem obscure but encapsulate the essence of Araki’s vast body of works. Arguably one of the most prolific postwar Japanese photographers, Araki is both loved by audiences and equally detested. His overtly erotic photographs have been labeled as pornographic and vulgar, and yet Araki admirers line up to be his muse. Such is the nature of erotic photography, holding the power to simultaneously ignite desire and push personal boundaries. In the ten-day exhibition presented at The Space by the Hong Kong Contemporary Art Foundation (HOCA), sex and sexuality were celebrated and embraced. “Up Close: Eroticism in the Works of Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki,” paid tribute to the three masters of Japanese post-World War II avant-garde photography. The exhibition questioned how sexual experience and the erotic are negotiated in contemporary Japanese society, where a flourishing sex industry ironically coexists in parallel with draconian obscenity laws and low birth rates.

Entering the ground floor of the spacious event venue-turned-gallery space, visitors were introduced to the works of Hosoe. Regarded as a forefather of Japanese contemporary photography, Hosoe revolutionized the medium in Japan by placing emphasis on visual aesthetics rather than using photography purely for documentation purposes. In his famous series, “Man and Woman” (1960), female and male bodies are abstracted—each image is infused with an erotically charged tension. For example, in Man and Woman #24, the smooth backside and buttocks of a woman is juxtaposed with three muscular forearms. The elegant sensuality in Hosoe’s photography immediately brings to mind Robert Mapplethorpe’s nudes, yet in placing men and women within the same frame, Hosoe’s tender images are less about the beauty of flesh and body, but more so a declaration of love.

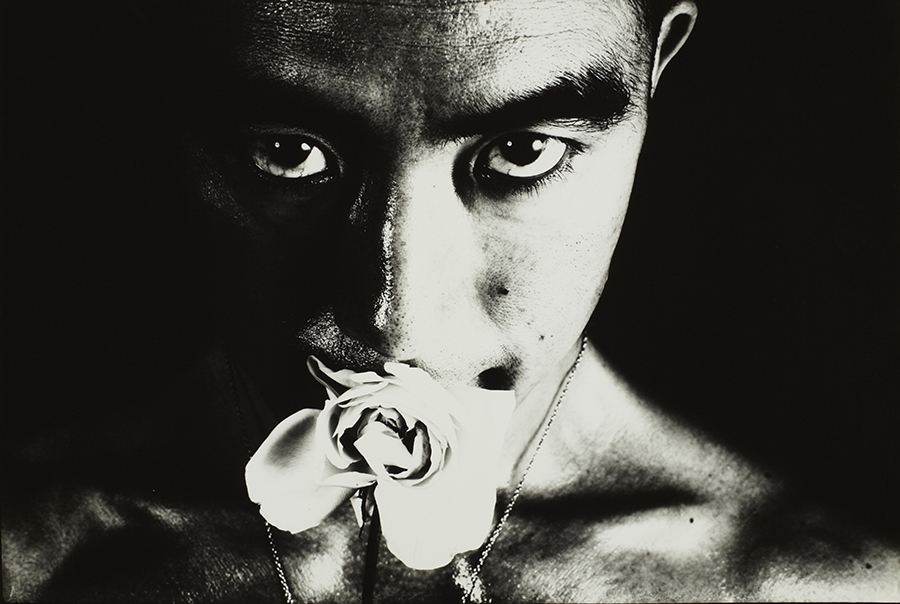

One of the most electrifying images in the exhibition, Ordeal by Roses #32 (1961) left one with an uncanny feeling of vulnerability. The monochromatic photograph is a portrait of author and poet Yukio Mishima (1925–1970). With a sharp gaze, Mishima glares intensely, with a rose in his mouth. Bathed with an undercurrent of primal sexual hunger, the image is both inviting and cautioning.

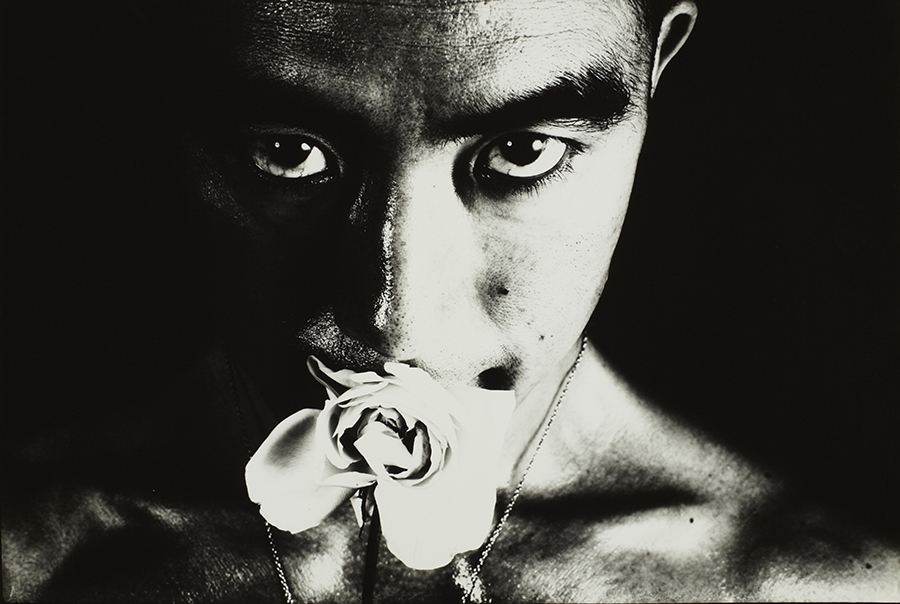

Upstairs, Japan’s representation of sex in contemporary culture was characterized by the self-taught Moriyama in “Tokyo: Meshed World” (1977). Three snapshots from the series including a page from Hentai manga; a sex advertisement from the street; and the legs of a shop-front mannequin, expose the grittier side of Tokyo’s consumerist culture. Moriyama, a former assistant to Hosoe, is notorious for his relentless drive and his talent to focus his lens on what others overlook. On the opposing wall, Moriyama’s 1987 “Tights” series adopts a stark visual aesthetic. A standout of the exhibition, the nine images of a woman’s legs in fishnet stockings distort the female body into flowing and seamless forms. Legs, feet and buttocks blend into curvaceous lines and shapes not easily discernible at first glance.

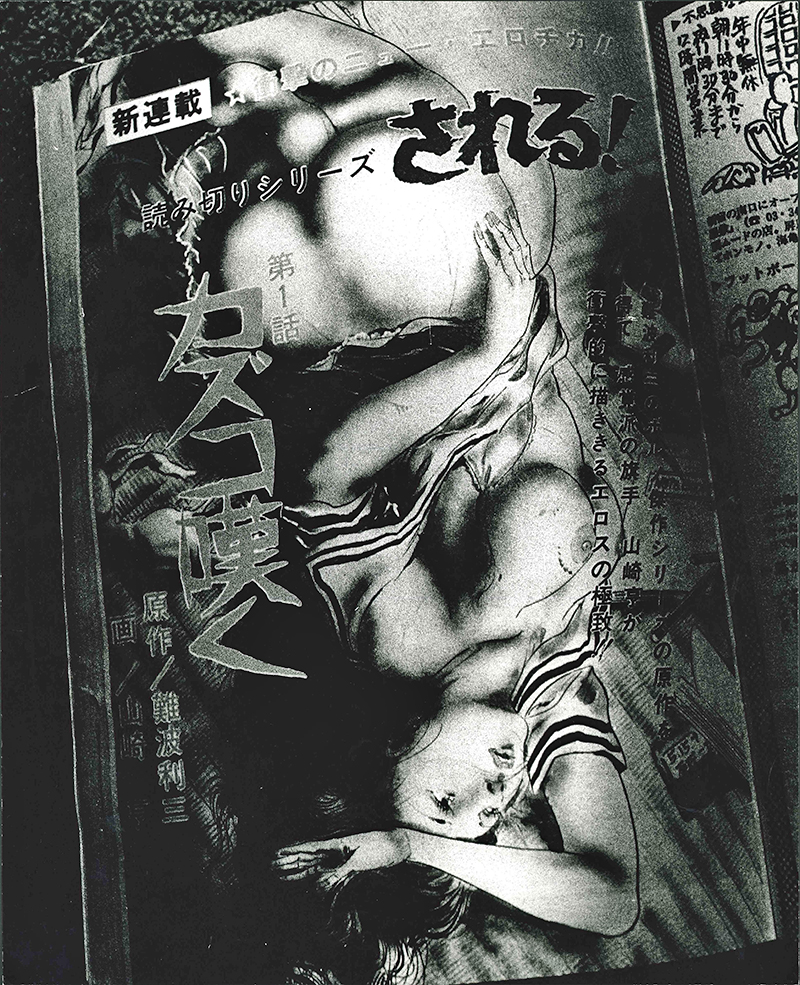

A contemporary to Moriyama, Araki has become notorious for his passion for the discipline of Japanese bondage known as kinbaku (meaning to tightly bind). Eight photographs from “Marvellous Tales of Black Ink” (1994) depict women in various states of undress, bound by rope with their exposed genitals covered by a drip of black ink. Reminiscent of traditional shunga—erotic art of the Edo period most commonly in the form of woodblock prints—each photograph bears nuances of Japanese culture placing them within a distinctive social context. In one photograph, a naked woman is suspended from the ceiling by a rope knotted to a beam, her face emitting pleasure, with a dildo discreetly framed in the corner of the image. In another photograph, a woman dressed in a kimono is tied against a wooden post, her left leg raised and bound tightly against her body, exposing bare legs and her genitals. With plump, lacquered lips, she gazes at the ground, appearing doll-like.

In his latest series “Love on the Left Eye” (2014), a different sort of eroticism emerges. Each image is blacked out on the right side, mimicking Araki’s lost of vision to cancer in his right eye, while the exposed half portrays his muse in various poses and scenarios. Despite the same sexual undercurrents and nudity in the images, the candidness of the photographs feels subdued. Nearby, an installation of an assortment of Araki’s color negatives illuminated atop a light-box table reveals the intimate and personal. Everyday moments, from mundane shots of food—a bowl of ramen, a plate of tofu—to social snaps and street lights and clear blue skies can be seen sharing a film roll with women in the nude and photos of celebrity Lady Gaga and artist Yayoi Kusama.

Araki once said, “If I didn’t have photography I’d have absolutely nothing. My life is all about photography, and so life is itself photography.” The same sentiments are applicable for Moriyama and Hosoe. For them, photography is life, and life is photography. In saying so, “Up Close” enforces the inescapable admittance that love and sexual experience is a natural part of life.

Denise Tsui is assistant editor at ArtAsiaPacific.

“Up Close: Eroticism in the Works of Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama and Nobuyoshi Araki,” organized by the Hong Kong Contemporary Art Foundation, was on view at The Space, Hong Kong, until October 25, 2015.