Shows

Tom Nicholson's “Drawings and Correspondence”

In art historian Anthony Gardner’s essay, “The Artist as Unsettler,” on the work of Australian contemporary artist Tom Nicholson, he identifies drawing’s power as its “inhabitation of temporality […], setting the record of what will be a picture’s past and yet outlining the sense of its possible futures.” The precarious, speculative, work-in-progress feeling that drawing elicits is synonymous in Nicholson’s practice with the contemporary political reality of Australia—the unstable subject of much of his multidisciplinary art. A committed archival researcher, Nicholson’s refined material approach and presentation belies the complex histories from Indigenous and colonial Australia that drives his art. These histories are further detailed in accompanying books of the artist’s correspondence that describe his research as an evolving narrative, copies of which can be taken home by visitors to his shows. It was apt, then, that Nicholson’s first survey exhibition—“Drawings and Correspondence,” at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane (IMA)—was focused exclusively on his commitment to drawing across the majority of his two-decade career. Curated by IMA executive directors Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh, the exhibition featured five of the artist’s major bodies of work, installed across four gallery spaces.

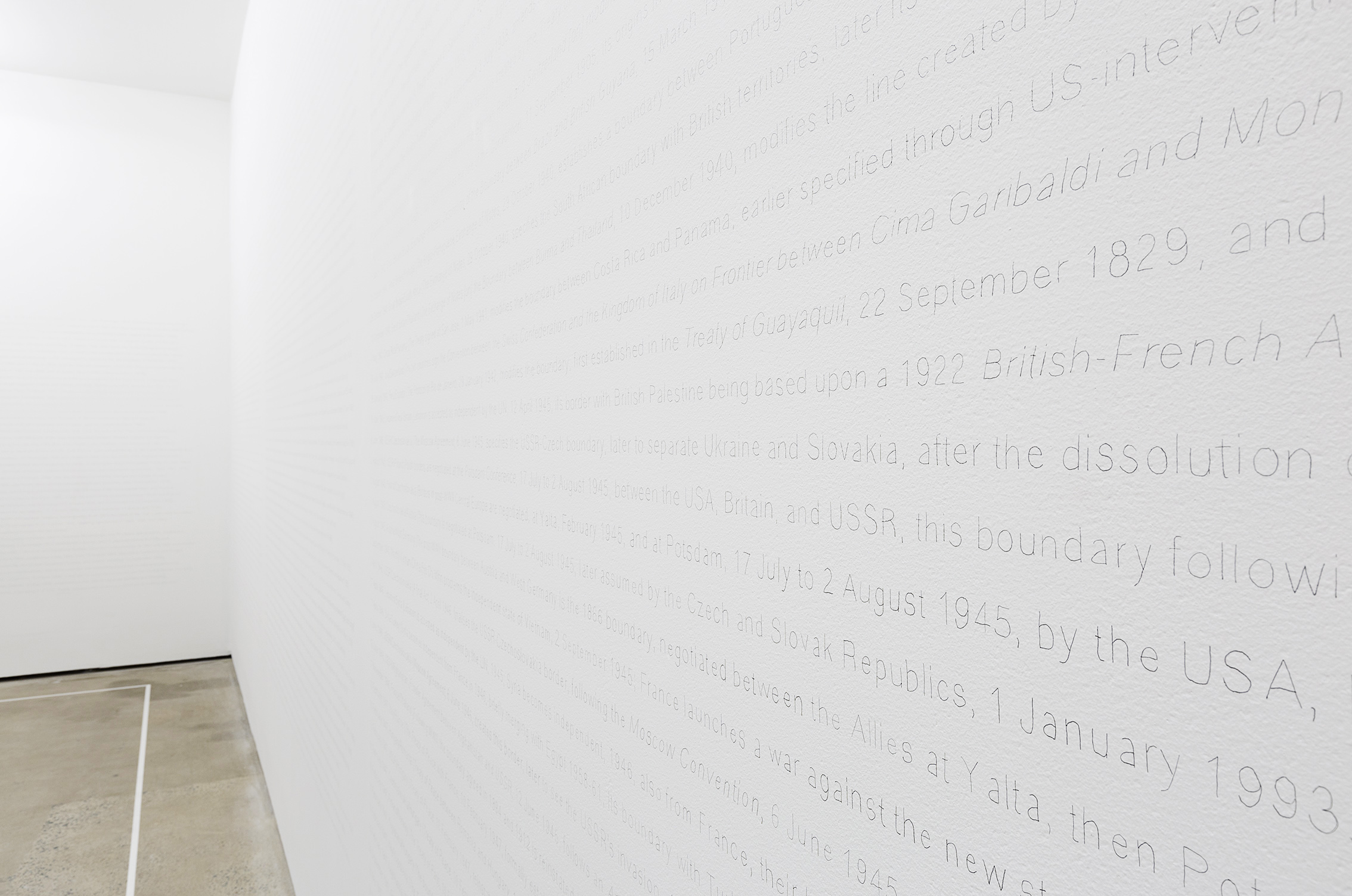

Entering the first space through a narrow, darkened hallway, the viewer was greeted by a seemingly blank, 15-metre-long wall, brightly lit from above. Moving closer, as one’s eyes adjusted, row upon row of thin, handwritten text in lead pencil became visible across the entire wall. The work, Untitled Wall Drawing (2005–18), documents situations around the world where countries’ borders have been drawn or redrawn since the Federation of Australia in 1901. The list begins with the “fixing” of the frontier “between French and Portuguese possessions in the Congo” on January 23, 1901, and concludes (in the 2018 iteration of this work) with Belgium and the Netherlands modifying the border between two municipalities on the Januaryn 1, 2018. Beyond visualizing the fluidity of geography, Untitled Wall Drawing speaks more through its absences: Australia, sharing no land boundaries with other countries, is not mentioned once, but Nicholson considers, through this silence, the colonial overwriting of Indigenous Australian societies and cartographies, and their ongoing repression. The work also alludes to a consistent technique in Nicholson’s practice where Australia’s past (and persistent) self-image as isolated and parochial is challenged by reanimating historical cross-cultural exchanges with Palestine, Israel, Indonesia, East Timor and others.

On the opposing wall, Drawings and Correspondence 3 (2010–11) announced the next two spaces’ focus on Nicholson’s deft skill with charcoal. In the second gallery, further works from the "Drawings and Correspondence" series (2008–11) were presented, including the first: a stunning piece measuring three metres long and two metres high, on loan from the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. The series is based on an archival photograph of a painting by artist Caroline Le Souef that accompanied a recreation of a “native encampment” at the Melbourne Zoo, constructed around the time of the city’s participation in the 1888 International Exhibition.

The three drawings inspired by this photographic trace revel in varying states of legibility. At times, Nicholson’s lines describe figures, perhaps lunging or dancing. In other sections, the image is negated into a field of luscious, velvety black. Also featured was a new co-commission: Gorge Photograph, 13 September 1939 (2018), in which this same tension between the figurative and abstract plays out within the context of the friendship between two important Australian artists, non-Aboriginal watercolourist Rex Battarbee and the Western Arrente artist Albert Namatjira.

Taking up an entire gallery space, Cartoons for Joseph Selleny (2014) recreates sections of Edouard Manet’s iconic painting, The Execution of Maximilian (1867–68). Perforated works on paper were struck with a bag of charcoal so that the drawing’s major outlines could be copied onto a wall in a Renaissance technique called pouncing. Nicholson presents the fragments of paper—each piece depicting a different isolated moment from Manet’s original—opposite a wall where the paper has been pounced directly onto the white surface repeatedly to create a vast abstract field of tiny charcoal dots, like the inverse of a starry night sky. Australia’s connection to Manet and the execution of Austrian Archduke Maximilian, the puppet emperor of Mexico and patron of Viennese artist Selleny, seems at first implausible. Yet, through his detailed research for Cartoons, Nicholson evidences and illustrates such unexpected histories—the eponymous artist arrived in Sydney in 1858 aboard the Novara, an Austrian frigate sponsored by the Archduke—that help to reflect on a more nuanced engagement with Australian identity. This sensitivity towards the impact of historically distant actions allows Nicholson to make genuine responses in the present that avoid the aggrandizement of other mechanisms for engaging with the past, such as traditional monuments or memorials. This exhibition strikingly describes the limits of representation when caught among contradictory historical and temporal forces: an impossibility that Nicholson’s potent drawings somehow convey.

Tom Nicholson's “Drawings and Correspondence” is on view at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, until June 2, 2018.