Shows

The World is Our Home. A Poem on Abstraction

At a time when the traversing of borders, by people, information and culture, is at the forefront of international consciousness and concern, Para Site, an independent art center in Hong Kong, is presenting an exhibition of four postwar artists whose outputs have shown just how fluid such boundaries can be. Held in Hong Kong’s North Point neighborhood, and jointly curated by local transplants Cosmin Costinas and Inti Guerrero, “The World is Our Home” highlights the ways that artists Tomie Ohtake, Tang Chang, Robert Motherwell and Bruce Nauman—though working outside of East Asia—were influenced by the vocabulary of traditional Asian art.

The first paintings that one encounters in the gallery are by Tomie Ohtake (1913–2015), the venerable Japanese-born artist who lived in Brazil from the outbreak of World War II in 1939 until her recent death. Hung in chronological order across a long wall, her paintings (all in oil, with the exception of one acrylic work on canvas,) are characterized by a drybrush technique that lends the abstract shapes and blocks of color an ethereal, blurred quality. The exception to the rule is Untitled (1984), a nearly all-black square painting with a diagonal white line jutting out from the canvas's bottom left. During the time when Ohtake was working in postwar Brazil, the dominant styles were Concretism and Neo-Concretism—dogmatic types of formal abstraction that rebelled against the pressure to create figurative art for an oppressive regime. Rejecting such styles, she pared down her own work to a restricted palette, reminiscent of the Modernist paintings that were being developed concurrently in Japan. Her paintings often incorporated calligraphic gestures and borrowed humanistic symbolism from Zen Buddhism. Interestingly, the influence on Ohtake’s oeuvre from all directions is evident: one of her oil paintings, Untitled (1963) looks almost exactly like one of Mark Rothko’s famous color-blocked canvases.

Hung next to Ohtake's works were paintings by Robert Motherwell (1915–1991), one of the youngest members of the Abstract Expressionist school, a group of mid-century American painters who created works in response to the nationalistic politics and culture of postwar United States. Highly intellectual and engaged, Motherwell participated in activist movements, anti-war rallies and fervently collected art and academic texts from around Asia. His paintings clearly reflect his interest in the East. A 1958 oil painting on primed board titled Frontier No. 12 consists of an energetic, gestural black brushstroke that looks like wet ink slapped onto the surface, its spirited vigor evidenced by the splatters surrounding it. His other works show similar explorations of calligraphic mark-making. Projected on an opposite wall is a slideshow of Motherwell’s famed “Elegy to the Spanish Republic,” a series of more than 100 paintings completed between 1948 and 1967. Intended to be a “lamentation or funeral song” for the Spanish Civil War, the paintings repeat a motif of rough black ovals in varying sizes and degrees of distortion on predominantly white backgrounds. Motherwell described the series as his “private insistence that a terrible death happened that should not be forgot.” Unfortunately, lighting in the gallery interferes with the slideshow, preventing the series from having an undisturbed opportunity to shine.

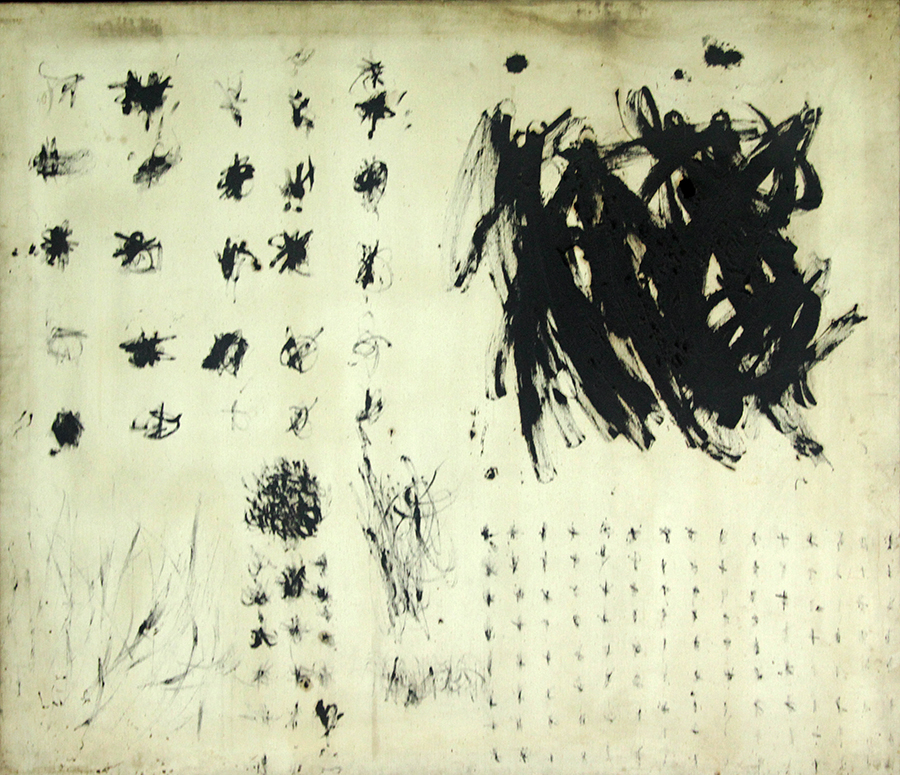

Some of the smallest and least suspecting—yet most captivating—works in the exhibition were those of Tang Chang (1934–1990), who had lived and worked in Thailand. Surely, his works are the most generously featured in the show, spread across two walls at the back of the gallery. Two vitrines hold his “poetry drawings” on paper, which are concrete poems made of repeated Thai characters strategically arranged into shapes to read as somber political commentary. Read in the context of the 1970s student uprisings in Thailand, the typographic compositions including such words as “people,” “escape,” “dictator,” “imprison” and “ghost” convey Tang's dissatisfaction with the country's oppressive monarchy. One drawing shows the character for “person” surrounded by dozens of the word “hunger.” Displayed on the the walls above, his large paintings on canvas are gestural, visceral and look as if they are passionate smears that were made with his bare hands. Seductively tactile and neutrally toned, all appear to have been painted quickly with a swell of emotion. Tang, who was of Chinese descent, routinely experienced unfair discrimination in Thailand due to the perceived Communist threat by Chinese immigrants in the country. His paintings have been called “double outcasts,” at times considered “too internationally abstract” and “too Chinese.”

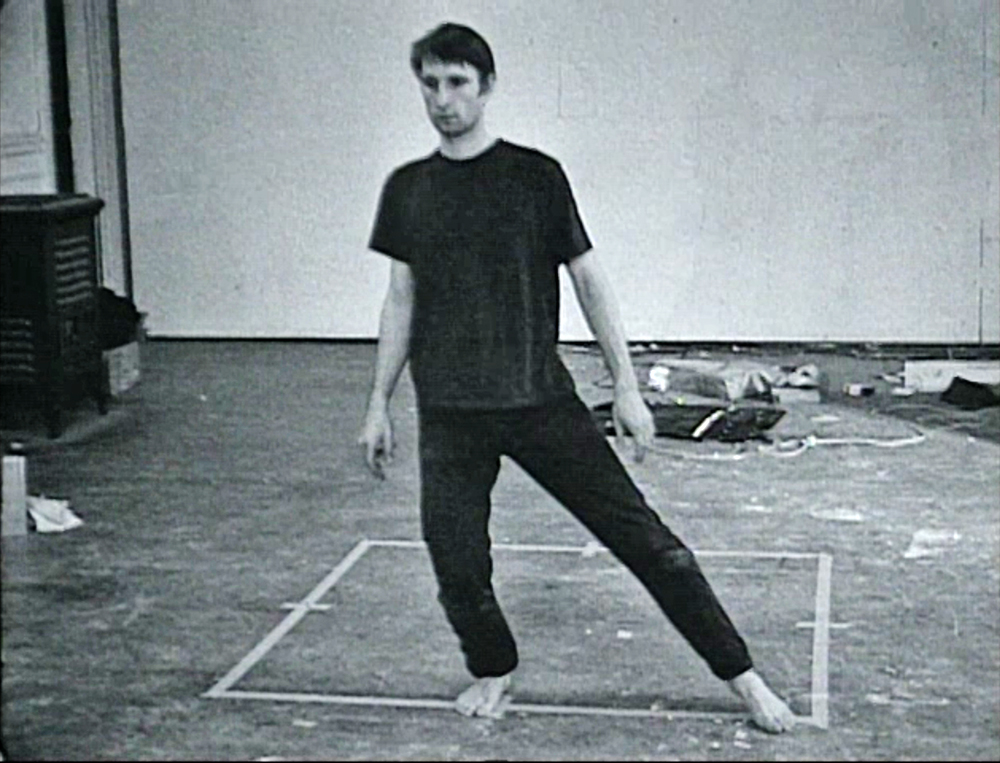

The other American artist featured in the exhibition, Bruce Nauman, is regarded as one of the most celebrated and innovative figures in conceptual art, known for investigating the nature of the creative process and the human condition. The Para Site exhibition includes one of his seminal works, Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square (Square Dance) (1968), today elevated to a symbol of postwar American conceptual art. Born of his insistence that whatever an artist does when he’s alone in his studio is art, the recorded performance shows Nauman moving methodically along a square made of tape on the studio floor. Influenced by literature, music, dance and cinema, the work is also a form of Zen-like meditation, expressing the passage of time through a repetitive and mundane activity.

While there is no evidence that these four exhibited artists knew one another, there are certainly formal similarities as a result of their common influence. Each painter primarily uses only one or two colors in their work, usually black, white, neutrals or red. Paint is often applied in three or four strokes, and usually with a large brush, tool or the artists’ fingers. Perhaps the most obvious aesthetic correlation between these artists happens in the work of Ohtake and Motherwell—specifically, the former’s Untitled (1962), a white canvas painted with one large, blockish black shape, employs similar bold black-and-white forms as Motherwell’s Iberia No. 30 (1969). However, when it comes to Motherwell, an artist who didn’t hail from an Asian country yet explicitly employed Asian painting techniques, one must ask, "Where is the line drawn between cultural influence and appropriation? What can duly be borrowed and what credit is consequently due?" The curatorial text of the Para Site exhibition suggests that Motherwell’s interest in Eastern art was a deep fascination rather than an “orientalist infatuation.” Indeed, his works did successfully interject an alternate narrative into a fiercely American postwar consciousness, offering valuable respite from the hard-edged machismo that defined the time, in the same way that the tenuous trend of primitivism did for 20th-century Europe. As if to address this question, the title selected for the exhibition, “The World is Our Home,” is based on a slogan employed by hundreds of Chinese volunteers serving on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War. The phrase—particularly pertinent today, as millions of migrants seek refuge and a solid sense of home outside of their native country—alludes to the arbitrariness of international borders and suggests that basic resources, culture and the freedom to express are the right of every human being.

“The World is Our Home” is on view at Para Site, Hong Kong, until March 6, 2016.