Shows

“The Kaleidoscopic Turn”

Spun through pieces of mirror and colored glass, the world is curtailed into its basic elements of light, color and form when seen through a kaleidoscope. What appears inside the cylindrical toy is like a voluminous, cosmic schema: a visual trick that paradoxically reduces and expands perception at the same time. It is this premise that underlies “The Kaleidoscopic Turn,” an exhibition of acquisitions from the National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) collection dating from 1940 to today. Not only does this exhibition provide an opportunity to experience key works from 20th-century art movements in Modernist optical abstraction, it also proves why such explorations are still both contemporary and exhilarating.

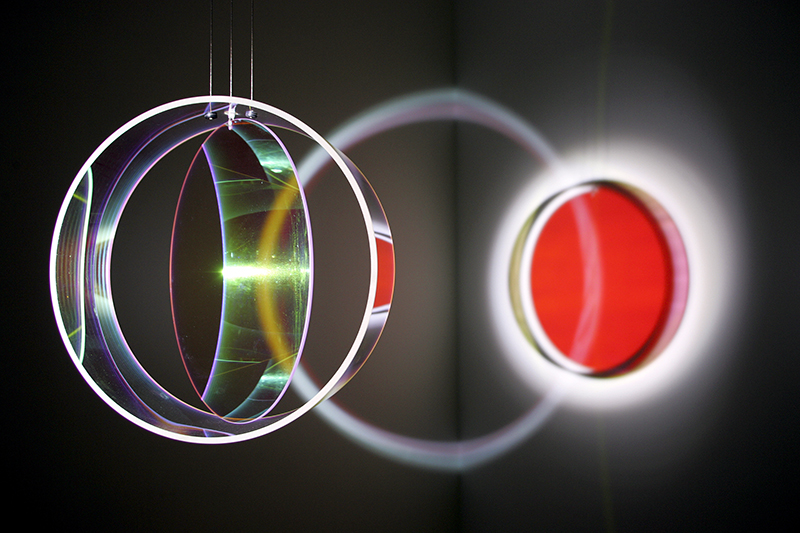

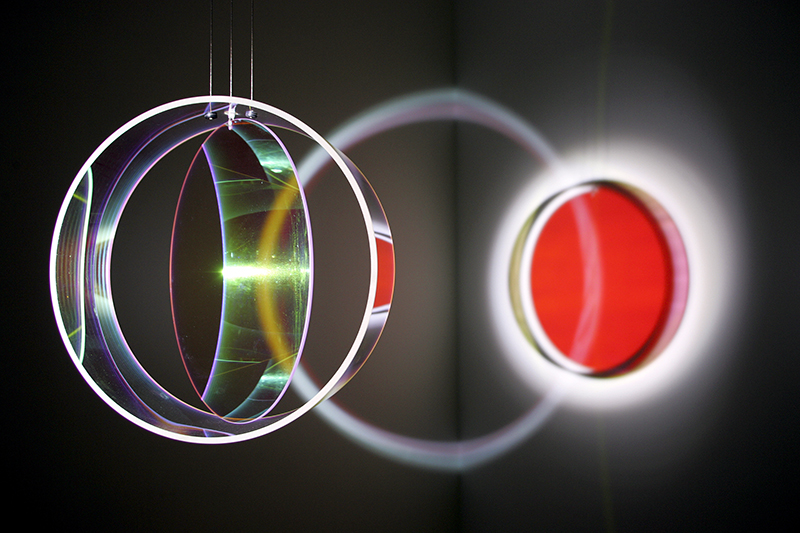

Hovering from the ceiling, and in orbit, Ross Manning’s mobile installation Spectra VI (2014) gesticulates at the exhibition’s entrance. Its arms—made of neon tubes, hardware paraphernalia and desk fans—pirouette around a shifting axis. As the mobile cruises at its own leisure, it is charming to watch its passé technology, which is choreographed to move in a gangling, kinetic dance. In a room abreast this space is Olafur Eliasson’s slicker Limbo Lamp (2005), which projects light through a seemingly modest apparatus made of circular acrylic sheets of various colors. As light enters the ocular installation—complete with iris- and outer cornea-like forms—various acrylic treatments (transparent, cut or mirrored) corral the rays into elegant throws across the gallery wall. These autonomous illuminations chase one another, moving through and out of the space encircling the viewer.

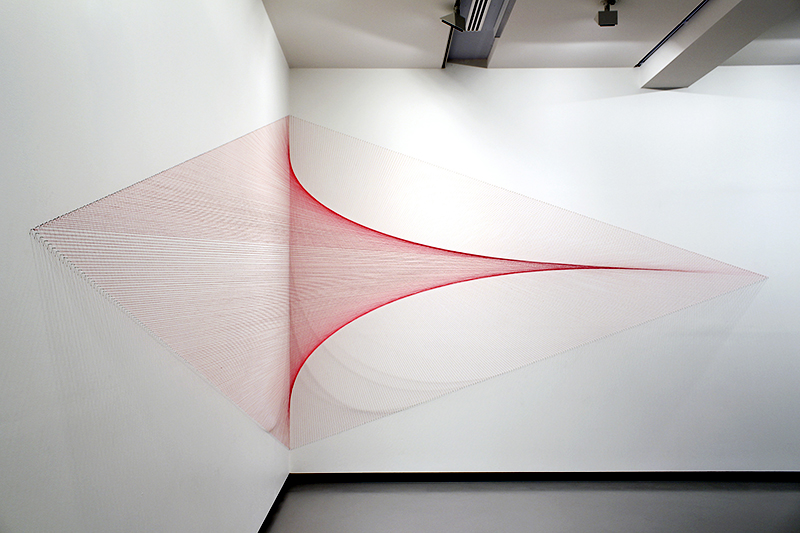

In keeping with the cosmic theme, there are certain nexuses among the exhibited works. Sandra Selig’s spellbinding Heart of the Air You Can Hear (2011) is a lattice of fluorescent pink threads, which binds the corner of a room with a tight, geometric web. This structure guides the eye, and mind, across its vibrant fibers: in visiting the gallery, it is common for children and adults alike to be stopped by an attendant from trying to touch the installation’s edges. This is forgivable, as the work’s circumference is truly difficult to perceive: the moment you capture it with your eyes, its high-key lines are swallowed by the competing brightness of the stark gallery wall. In tandem, the NGV’s recent acquisition, Jonny Niesche’s Total Vibration (2014), quivers nearby. This similarly rose-colored piece—a series of hazy concentric circles, ranging from pastel pink to vermillion to charred-sienna at its center, painted on a translucent voile surface—hums and hypnotizes. Its surface material, as well as visible stretcher bars, reminds us of painting’s historical desire to consider and reflect on the process of optics and illusion—not as an afterthought, but as a subject in itself.

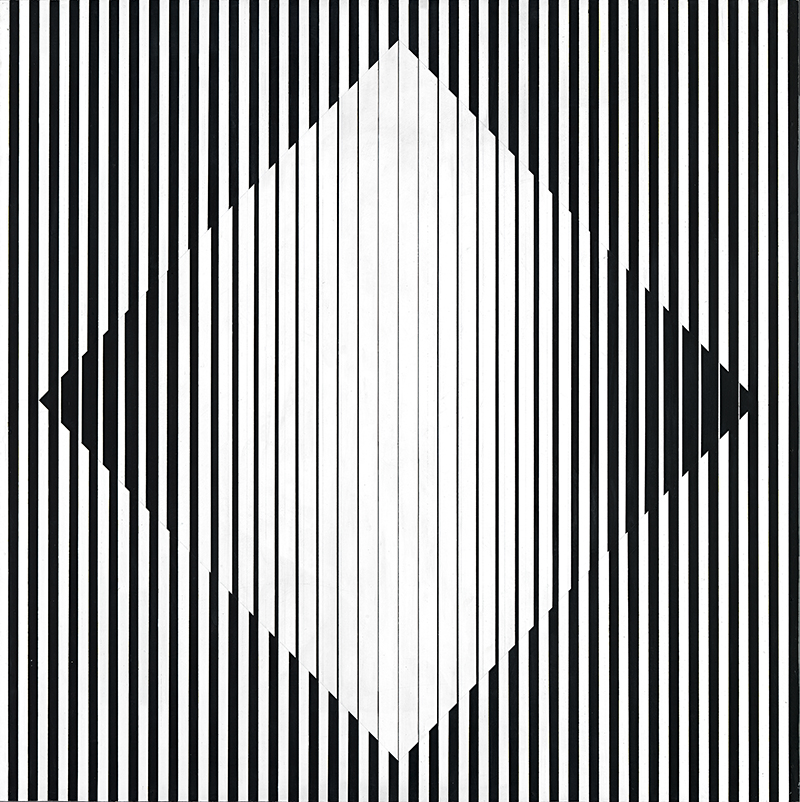

This conceptual engagement is also present in a number of other formal considerations. Three videos from Daniel von Sturmer’s "Tableaux Plastique" series (2008) seek to explain the connection between viewer, object and image. Using screens to replace the traditional pictorial frame, the videos show a trio of simple art experiments using acrylic paint and other materials. For example, one features planes of paint shifting across each other and altering others’ tone. Another screen shows many droplets of white paint descending onto a black surface to create an expansive pattern. The final, and perhaps most mesmerizing, video presents a stream of paint that plummets in various intervals and shades of grey, creating a perfectly expanding void of concentric circles. These videos demonstrate Sturmer’s ongoing exploration of space—pictorial, real and recorded—where basic image-making processes are converted into expansive, almost science-fiction-like encounters. Through an aptly curated display, prominent Op-artist Bridget Riley’s black-and-white painting Opening (1961) stares down the barrel of Sturmer’s circle video. Riley’s tempera painting depicts a monochromatic, diamond-shaped void made of carefully constructed geometric forms. In a perfect example of her long and still-current practice, Opening engages the viewer’s eye with a series of conflicting connections, where the central void-shape protrudes one moment and recedes the next.

In the exhibition, subtle incidents—such as the primary-color ribbons of light that are cast onto the concrete floor by Anne Marie-May’s RGB (Mobile) (2013), David Thomas’ modestly scaled field paintings or Matt Hinkley’s lollypop-sized amalgams—don’t go unnoticed. Of these quieter moments, the late Robert Hunter’s painting Untitled (1998) is a vision for meditation. A geometric field consisting of many subtle shifts in “whiteness” asks for patience from its viewer. Created on board to ensure absolute flatness, its discreet shapes are differentiated through a careful attention to the various material qualities possessed by acrylic paint: some forms are glossy, while others are matte; many are transparent, building opacity through a multitude of layering. Overall, this delicate work accumulates thickness at its center, where the paint is thickest, while its edges reveal the complex mosaic upon which the white field is constructed.

Alongside these discussed works, the remaining exhibition offers further delight. Visitors to “The Kaleidoscopic Turn” are gifted with the experience of seeing many iconic examples of abstract and modernist Op-art movements found in the NGV’s collection. They will also be made aware of the still-relevant contemporary exploration of various materials, and their ability to convey our sensory experience of the world—which, in the words of Eliasson, take viewers outside of themselves to become the very object that is being looked at.

“The Kaleidoscopic Turn” is on view at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, until August 23, 2015.