Shows

Taipei Biennial 2023: The Promises and Perils of a “Small World”

How small is the world? Small enough that at the Taipei Biennial 2023’s opening weekend (November 16–19) at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), you could experience Indonesian electronic musician Julian Abraham Togar jamming with the abstract “kinetic paintings” created live by 87-year-old Palestinian artist Samia Halaby, using software she programmed. Small enough for a meteorite, a relic from the time of our solar system’s formation, to fit on a child’s fingertip, as captured by Taiwanese American artist Arthur Ou in the photograph Untitled (Octavia with Meteor 1) (2020). Small enough that the microchip processors made in one Taiwanese factory using local labor and resources—as depicted in Su Yu-Hsin’s film Particular Waters (2023), about a female water-truck driver—keep the globe’s super-power rivalry suspended on the brink of devastating planetary conflict. In matters of scale, the small (the microscopic, the local, the immediate, the personal) can wield sizable influence on the large.

,%202020,%20chromogenic%20print,%2020%20x%2024%20inches_Fotor.jpg)

Conceived as a reflection on our post-pandemic shifts in perceptions, and awareness of ourselves and our communities, the Taipei Biennial 2023, titled “Small World,” explored ideas of scale and proximity, intimacy and division, and isolation and interconnectedness. The Taipei Biennial curatorial team who convened 58 artists and musicians comprised Hong Kong-based Taiwanese independent curator Freya Chou; New York-based e-flux journal editor Brian Kuan Wood, who has family roots in Taiwan; and Beirut Art Center director and curator Reem Shadid, who is Palestinian and not “from Lebanon” as she was repeatedly described in official contexts. In the co-curators’ words, the title “suggests both a promise and a threat,” for the ways that a “small world” might invoke deeper connections between individuals in a community while also evoking the potential for isolation, in-grouping and out-grouping, information silos, and physical and psychological spaces of confinement. A trope that exists across societies and languages, this phrase points to how the networks that bring us closer to others have liberatory, restrictive, as well as divisive potentials. These are the urgent dynamics for our 21st-century societies, as our immediate surroundings are the sites and sources of both solidarity and conflict.

The larger world, its divisions and stark realignments, were very much in attendees’ consciousness. At the opening ceremony for the 13th Taipei Biennial, TFAM director Jun-Jieh Wang referenced the staging of this exhibition amid numerous unspecified “geopolitical tensions” in his opening speech. This is the island of Taiwan in late 2023, where the outcome of national democratic elections in mid-January 2024 will have societal and global ramifications. Taking the stage after Wang, Shadid spoke pointedly and poignantly about the struggle of mounting an exhibition in the 41 days (at that moment) since the Israeli military began its genocidal campaign against Palestinian people in their homes in Gaza and the occupied territories of the West Bank. She read a poem by the Syrian writer Riyad Al-Hussein with the recurrent refrain of a “small, narrow room” iterated as a space for an artist’s solitary creativity, for human intellection, as well as personal suffering and death. For those listening, it was impossible not to think of all those thousands of souls invoked by Shadid wandering the Earth in the last 40-plus days who have been killed in the most brutal ways in their homes. When a refuge becomes a tomb, it is the smallest and cruelest of all possible worlds. The hour-long event was—compared to how official opening ceremonies usually go—a succession of deeply moving personal expressions of what it meant for three individuals to work together and with a supportive team.

“Small World” is, physically, an event contained within the galleries of TFAM, unlike many biennials worldwide that expand into the city. Reflecting many artists’ concern for modes of care and emotional support, several works of “Small World” also created their own audiovisual universes. In the TFAM courtyard, Natascha Sadr Haghighian’s installation Watershed (2023) comprised six amorphous, bodily-like forms composed from reflective plastic animal figurines and perched on top of walkers; they doubled as resonant bodies for speakers for an immersive musical composition based around a Cantonese pop song by Karen Mok with lyrics translated to Minnan and Mandarin. Also featuring music as a core element to its experience of space, Jacqueline Kiyomi Gork’s installation’s Not Exactly (Whatever the New Key Is) (2023) is a near-pitch-black room with a maze of inflatable black walls filled with a medley of songs—the music crescendos and then the walls dramatically collapse and the sounds of air-blowers fill the room with strangely harmonic frequencies. In each of these two works, emotive strands of pop music are expanded and stretched to fit with abstracted sculptural installations about forms of collapse, care, and support at key times in one’s life.

On the flip side of the “Small World” theme, the tragedy of isolation played out differently in two video works by Jen Liu and Basim Magdy. Liu’s Land at the Bottom of the Sea (2023) takes the disappearance of female labor activists in China as its subject, overlaying stories of silencing and tragedy with spectacular imagery of underwater performers on a coral reef in the dark. Painter and filmmaker Basim Magdy’s The Dent (2014), composed from footage he shot on Super 16mm, obliquely narrates the tale of a small town in the grip of a collective delusion. Though made a decade ago, Magdy’s work felt as relevant as ever: reflecting the collapse of a sclerotic social order, which he experienced in Egypt during the turmoil of the pre- and post-Arab Spring era, and presaging the fracturing felt in many other countries in subsequent years. On another emotional register altogether—somewhere between the maniacal and the philosophical—were the animated figures in Li Yi-Fan’s video What is Your Favorite Primitive (2023), which engage in a meta-level self-dialogue while the creator/artist manipulates them into contorting, destroying, and disfiguring themselves in a chaotic multiverse of special effects and digital-animation tropes. These are the prisms in “Small World” through which insularity can tip into disappearance, delusion, and psychosis affecting individuals and society at large.

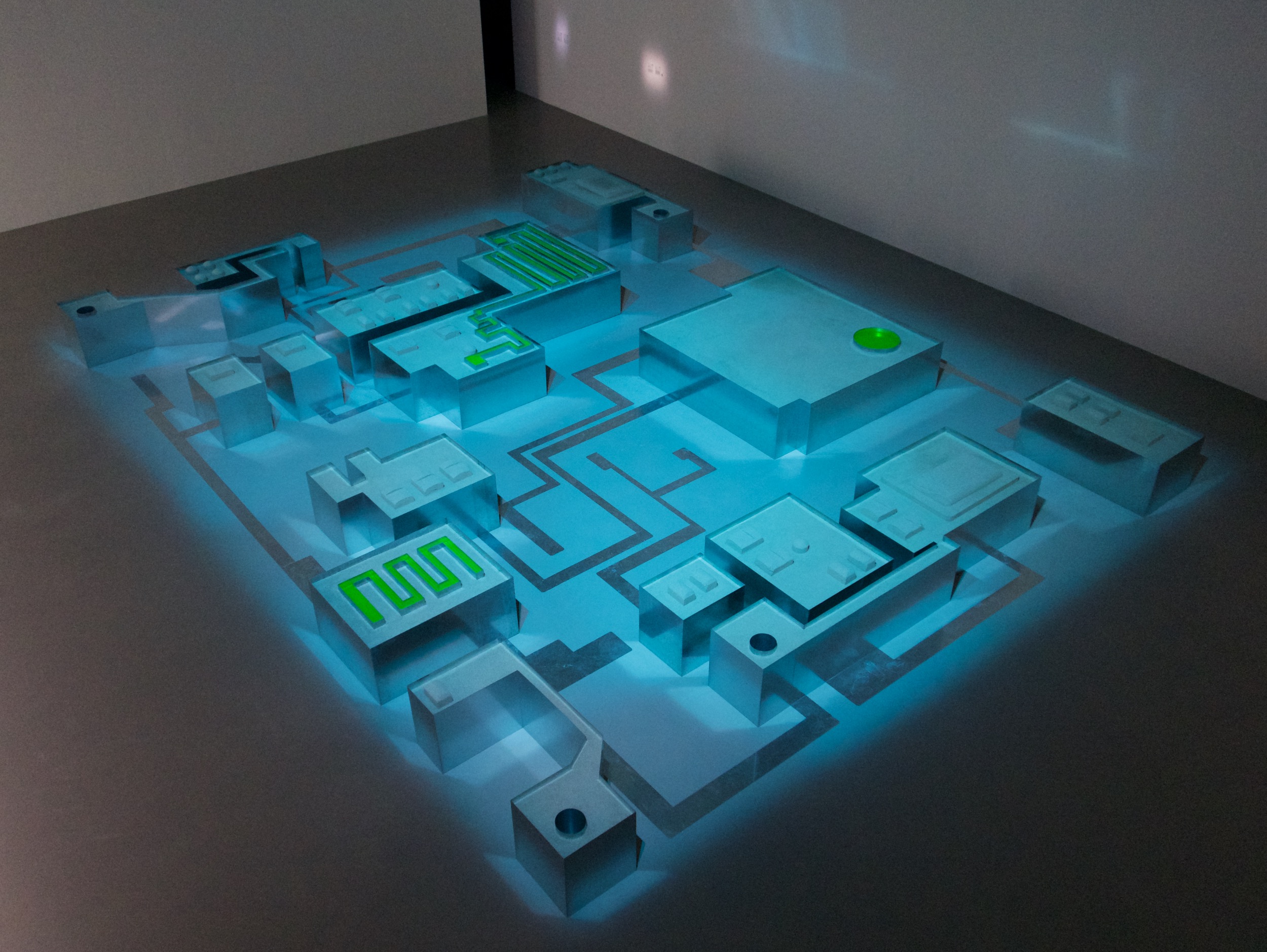

“Small World” was loosely, and gently, curated. Without a strong narrative or political thesis, the Biennial was full of unexpected but welcome conversant pairings—not didactic but political nonetheless. Balinese artist I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih’s paintings of anthropomorphic figures were exhibited a few rooms away from Lebanese artist Huguette Caland’s bodily abstractions from the 1970s. Ellen Pau’s mediation on the concept of the timeless in the forward-and-reverse capacities of video imagery in her iconic Recycling Cinema (2000) silently conversed with Kim Beom’s audio-less mashup of footage inverting the predator’s hunt for prey with a loop of an antelope seen chasing a cheetah. The Ivantan-language poetry rendered on the floor in large terracotta letters by Pio Abad (who, for the first time, visited the Taiwanese island of Lanyu, which is just north of the Batanes islands in the Philippines where his family is from, to research their shared cultural-linguistic formations) resonated with Seher Shah’s text fragments turned poems in the print series, Notes from a City Unknown (2021). Patricia L. Boyd’s ongoing film project Operator (2017– ), for which she programmed cameras to scan an empty recording stage uncannily felt like an updated version of Takashi Ito’s structuralist film Spacy (1981), shot in a giant, empty gymnasium filled with pictures of the same space. Nadim Abbas’s installation Pilgrim in the Microworld (2023) of steel sandboxes arranged like a lifesize semiconductor reflected the brutalist forms captured by theorist Paul Virilio in his photographic catalogue of abandoned German military bunkers along the coast of France. The curating facilitated many dialogues or small-group conversations—about topics ranging from the use of machines in DJ’ing, filmmaking, and installation-making, to the experiences of grief and trauma, to the proximity and isolation of bodies, to the nature of abstraction and scale, and countless other threads. It made the experience of the Biennial more like walking through the rooms of a house party rather than—as is the case with many other exhibitions—akin to listening to a symphony with a central curatorial figure as a conductor of artistic voices.

“Small World” was generous: to artists for giving them the space their artworks need, and to audiences for providing a dynamic gathering of artworks without an onerous amount of discourse. Small as the exhibition is, by biennial standards, you can easily navigate it in a single visit, or you can spend more than a day there, with several hours of films to watch—highlighted by Jumana Manna’s feature film Foragers (2022), depicting Palestinians’ practice of gathering wild herbs central to their cuisine and the Israeli state’s efforts to criminalize access to the land. An unfolding performance program in the Music Room, a dedicated space designed with curving blue steps designed by the Bethlehem-based architects AAU Anastas on the lower level of TFAM, will play host to residencies by dj sniff and, later, Wok the Rock and Julian Abraham Togar.

Every contemporary art biennial is a bringing together, a gathering, of worlds. Every biennial—triennial or mega-exhibition—becomes a temporarily rooted occasion for a unique community to form, and in this way a site for world-building and world-reorienting to happen, with the intention of producing reflections on our contemporary reality. But “Small World” lived up to its name in how uniquely intimate, empathic, and concerned it felt for both its participants and its audiences—and for what is happening to all of us out there.

HG Masters is deputy editor & deputy publisher of ArtAsiaPacific.