Shows

Tadaaki Kuwayama’s “Radical Neutrality”

In 1964, Tadaaki Kuwayama released a statement explaining his art to an increasingly interested audience: “ideas, thoughts, philosophy, reasons, meanings, even the humanity of the artist,” he said, “do not enter into my work at all. Here is only the art itself. That is all.” By this time, Kuwayama had been living and working in New York for six years, the same city as minimalists like Donald Judd and Frank Stella. He found himself in good company as he sought ways to bring neutrality to his paintings, one element at a time.

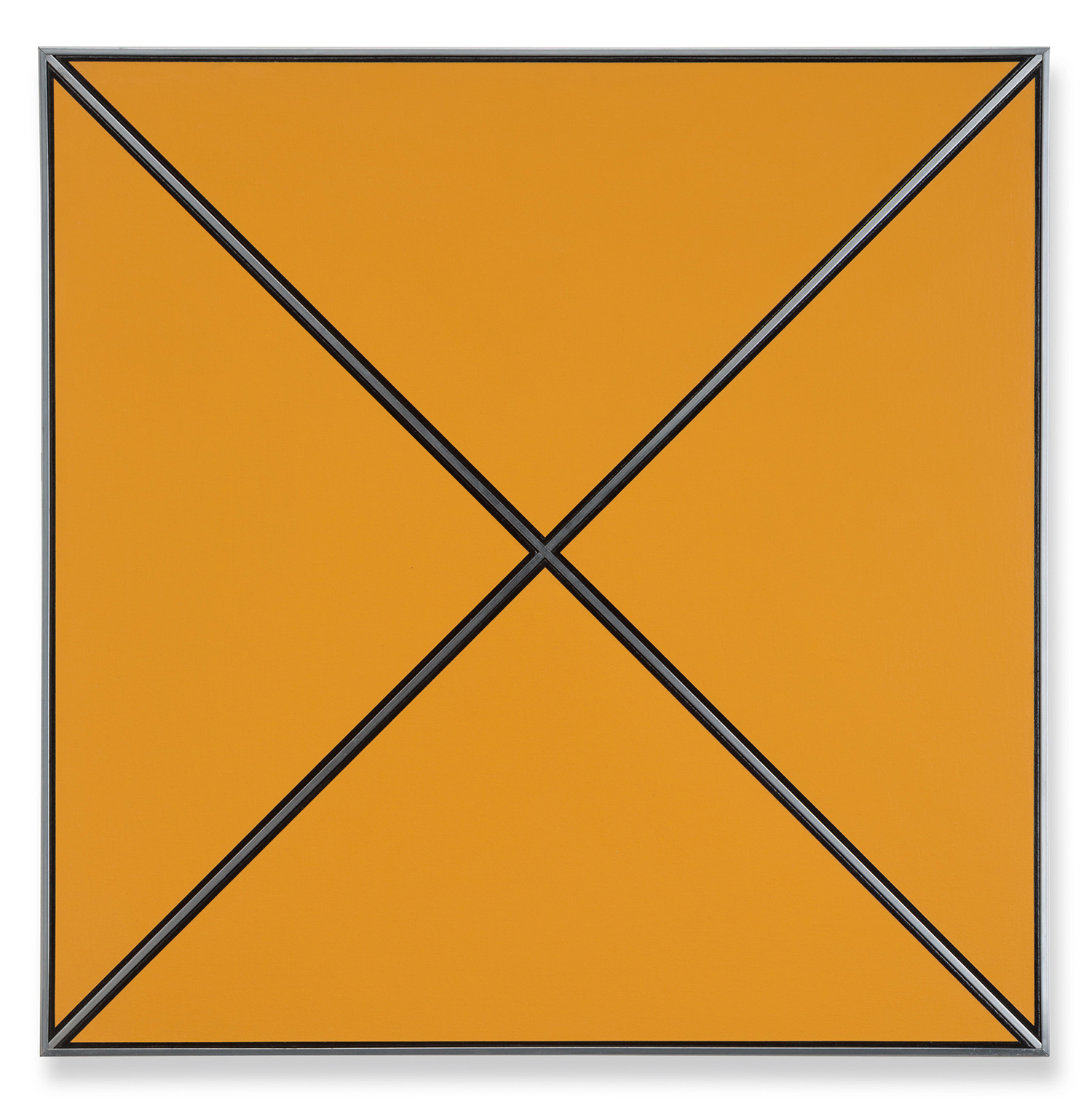

To this end, the “cross-paintings,” which are among Kuwayama’s most easily recognizable works and make up the majority of “Radical Neutrality” at London’s Mayor Gallery, consist most often of four equivalent square canvases slotted into an aluminum grid and bordered with thick black lines. Each constituent canvas is painted uniformly in a single color to eliminate any hint of expression, and a clear layer of solvent is then applied to make the surface reflective, so that it “blends into the surrounding space.” The nature of the grid—as elaborated by many artists working within the minimalist idiom—eschews composition. Through its potential for infinite repetition, the grid even undermines the limits of spatial specificity. With these ideas in mind, Kuwayama claimed to create works that cannot be judged by aesthetic conventions, in terms of “good or bad.”

There’s an inevitable and paradoxical hubris in much art of this kind, where an artist claims to be able to remove themselves from their creations as an achievement. Ironically, the continued perception of the works as independent often necessitates the involvement of their author, lest history and commentary take over.

These pieces are not intended to be looked at for a prolonged period of time, rather something of their concept is meant to be understood intuitively at a glance. Without the artist present, a viewer may not know this, and it doesn’t take more than a moment for meanings to creep into the work. Information is immediately relayed—then understood and interpreted by the viewer—via the use of canvas, because canvas has history. That familiar warp and weft tap into centuries of art that cannot be brushed aside simply by avoiding brushstrokes. A closer look also reveals that the aluminum frames are attached to their wooden backs using screws. If we are to look at these works without heeding the conventions of painting, we may take such details into account, and what we read in them is the artist’s hand. Kuwayama tells us what the reflective surfaces of the pieces and the grid arrangement of the colored plains should do, but without his statements, any number of interpretations might be made of this body of work that is intended to be precise and homogenous.

Such is the artist’s continued involvement with his creations that, for past museum shows, he has asked that special spaces be constructed to house them for optimal neutrality. At Mayor Gallery, however, such control was not possible. Where the cross-paintings—which are all untitled and identified only by a serial number—would usually be grouped by their colors in order to detract from their individual effects, the displayed pieces were in a variety of bright hues. Among the only two works that were not cross-paintings, Untitled (TK1724-’61) (1961)—a freestanding sculpture made using paper and wood—was placed next to the gallery’s main window. In a figurative turn, the all-black sculpture’s two sets of raised stripes recalled the slats of a window blind, with foreign meaning once again tainting neutrality.

Responses such as these may seem trifling, but when a body of work nears a state of purity, exceptions find (perhaps unwanted) prominence. Kuwayama has sought to create anonymous works to which a viewer may not know how to relate. In having to reiterate the works’ intentions, anonymity becomes evasive; as these pieces are assimilated into the annals of art history, viewers implant definitions where the artist dictates there should be none. Ultimately, lofty pronouncements detract from the reality that these creations are wonderfully crafted, aesthetically pleasing and deserving of praise.

"I believe my concept can be arrived at as a timeless condition,” Kuwayama said in an interview with the late art critic Kōji Taki for a 1996 exhibition catalog, which accompanied the show “Project ’96.” That may be true, but not in a timeless way.

Tadaaki Kuwayama’s “Radical Neutrality” is on view at Mayor Gallery, London, until July 28, 2017.