Shows

Susan Te Kahurangi King at Marlborough Contemporary in London

The Fanta Jester—a 1960s soda pop icon with a vast, round orange head, broad clown smile and petite, red circular nose—tumbles across a series of drawings by Susan Te Kahurangi King. Hanging from the sky, hidden among geometric blocks or spewing liquid from his mouth, this figure is consistently present in the varied drawings installed at eye level at Marlborough Contemporary’s London gallery.

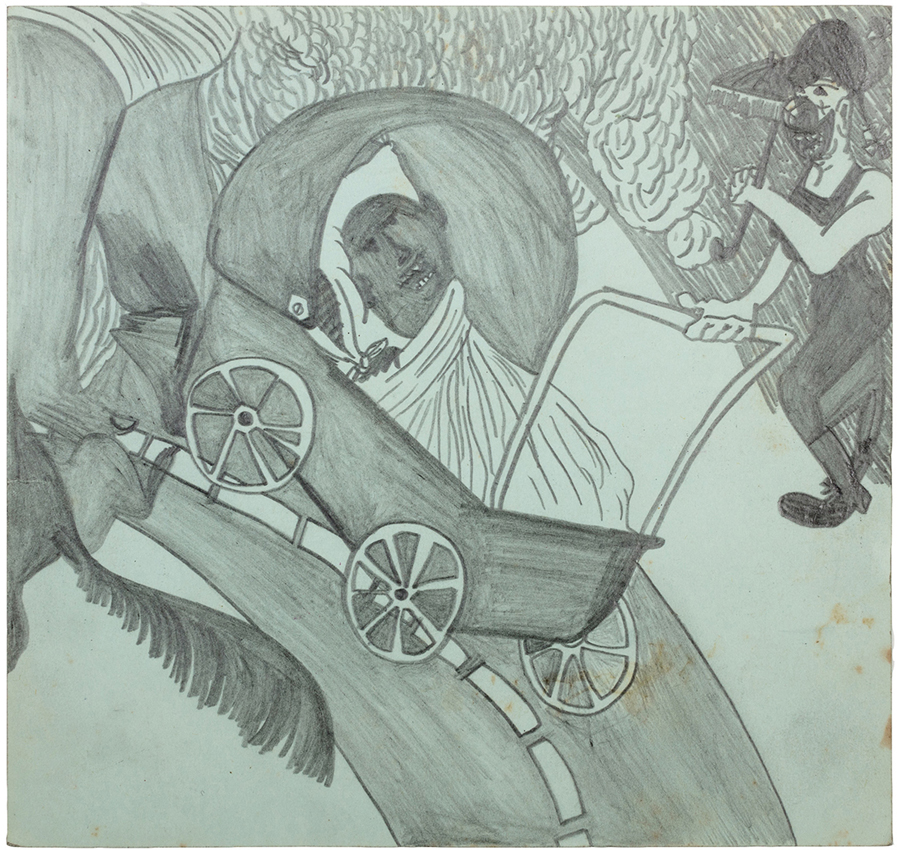

Made in the years after the artist ceased verbal and written communication, these works are King’s only form of interaction with her surroundings and other people. Using a mixed vocabulary of cartoon characters—Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny and Noddy—along with cityscapes and awkward dystopic landscapes, there is a resounding, latent darkness and frustration in the artist’s expressions. An untitled drawing made by King in 1964 establishes this tone: The presentation of a crazed baby in an antiquated pram being pushed toward a mess of body parts and pencil squiggles is alarming. The figure steering the pram equally brings chills to the viewer. Tightly drawn at the edge of the paper, a clown with swinging pigtails and wearing a form-hugging dress—though the character may actually be male—hysterically grins, evidently enjoying the child’s impending doom.

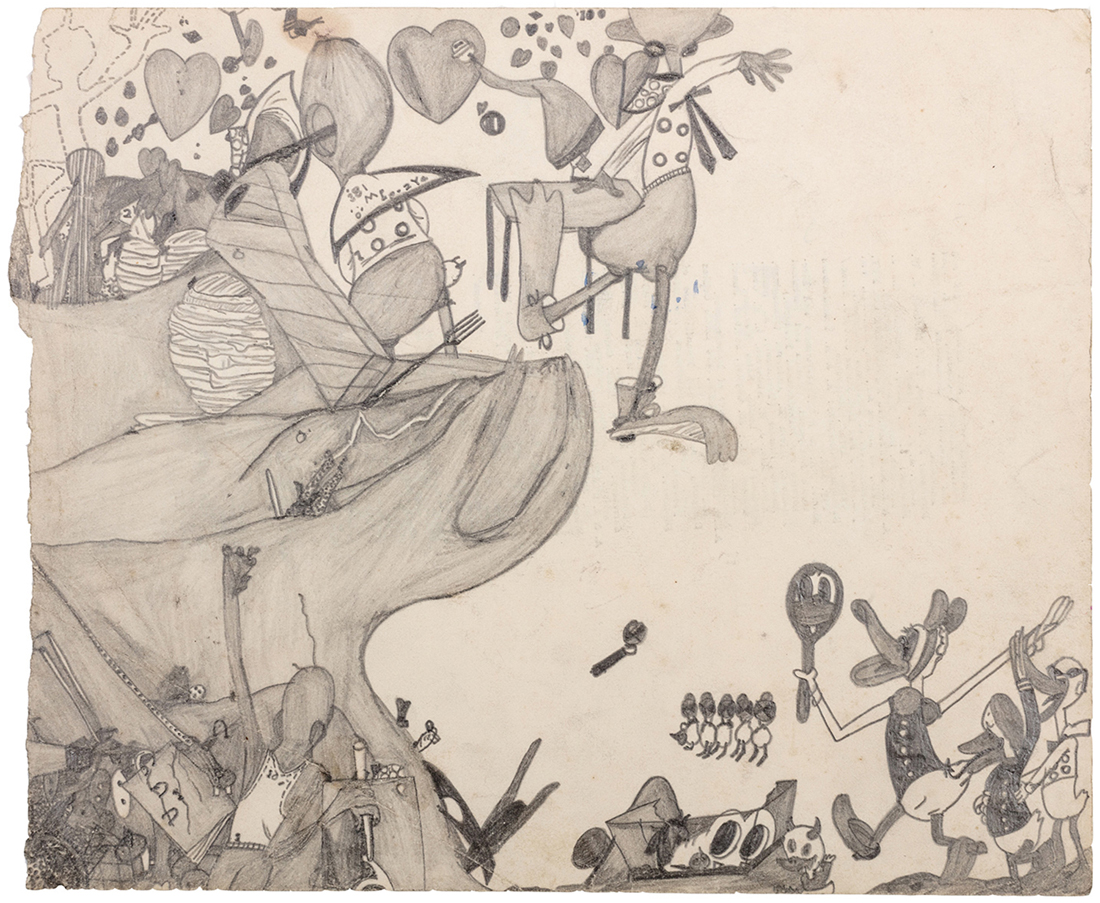

Another group of inanely smirking personalities, modeled after Donald Duck, observe a vortex of carnage in another untitled drawing created circa 1965. On top of a cliff formation, a sightless, bulbous cartoon character, donning a cape, stands with its mouth open. A chain-like tongue extends, attaching itself to a disproportionately large tombstone that wobbles above a thin fork. The utensil’s prongs point in the direction of a webbed foot, belonging to yet another absurd character. The narrative is challenging to decipher. Each element of the drawing appears independent, plucked from the artist’s immediate environment and added to the page.

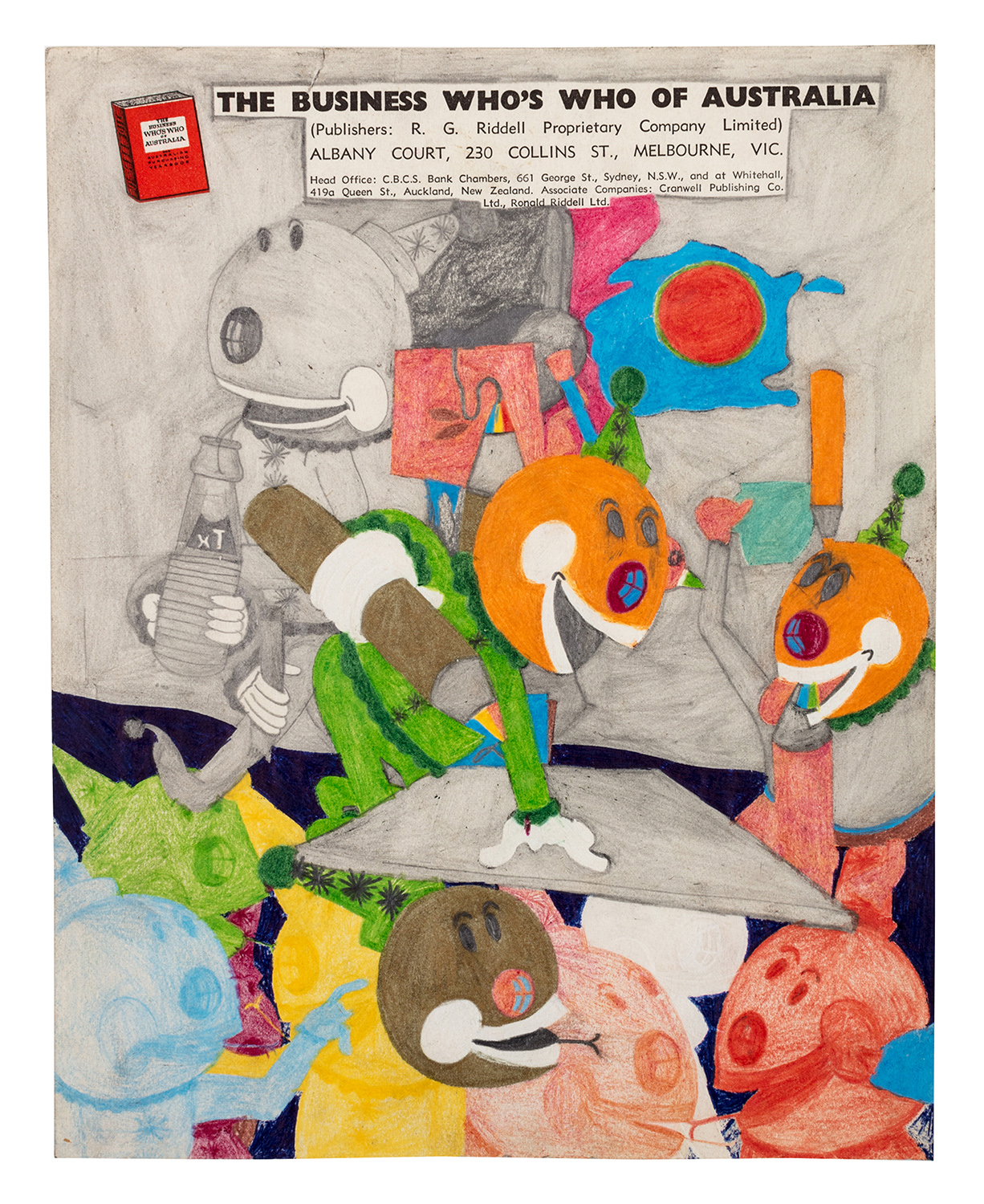

Accumulating forms, layering characters and tessellating figures are all characteristics of King’s practice. A colorful piece drawn circa 1966 or 1967 on a sheet of advertising paper crams variations of the Fanta Jester together in a rowdy mass of limbs, shiny noses and broad smiles. The printed text, advertising a book, The Business Who’s Who of Australia (1966–2008), is left untouched. King preserves the words, tracing a box around them so that they are kept pristine. In other drawings made on newsprint, letters and words become part of the artist’s unrestrained scenes. Whether the artist values typefaces as aesthetic objects is unknown, but as her sister told me, King prefers to work on scrap paper, such as a fabric sample card, again with its the lettering left undisturbed.

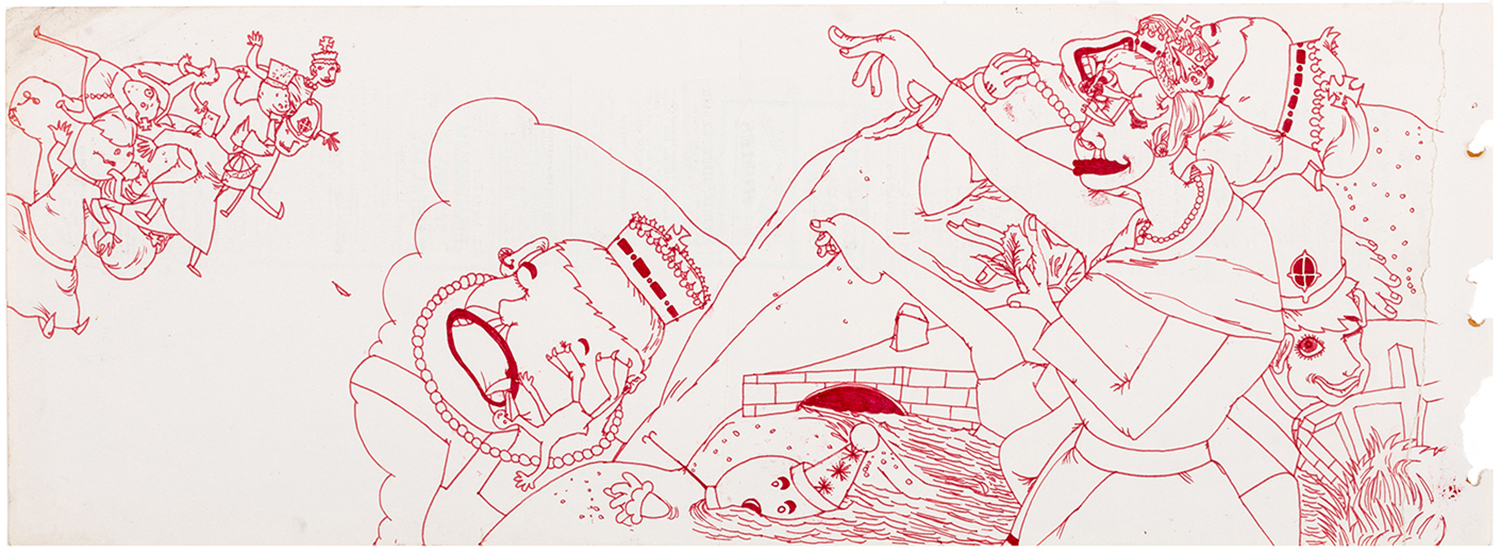

Three of King’s pen works were also introduced in the exhibition. Their lines are more assured—crisper, more defined, as would be expected with ink—comprising constellations of bizarre characters tangled with each other. A panoramic work from 1966 or 1967 records a state visit to New Zealand by Queen Elizabeth II, who was then Head of the Commonwealth. She is recognizable by a small crown and her stately face, which is pulled apart and trampled over by a sharp-beaked duck. From a nondescript pool of liquid, Mickey Mouse’s hand emerges and pulls a row of pearls from her nose. A younger version of the monarch, suspended in a cloud-like structure, floats nearby. Her mouth gapes, like that of a fish, ready to swallow the duck that is flailing by her face. As with the rest of these works, this drawing functions as a stream of consciousness sparked by the artist’s observations of the world around her. King’s visually complex and intense creations not only express her thoughts, but also are fundamental to her experience of reality. They are the predominant articulation of her character and personality. The autobiography that emerges is both alarming and confounding.

Susan Te Kahurangi King’s solo exhibition at Marlborough Contemporary, London, is on view until July 1, 2017.