Shows

Suki Chan’s “Lucida”

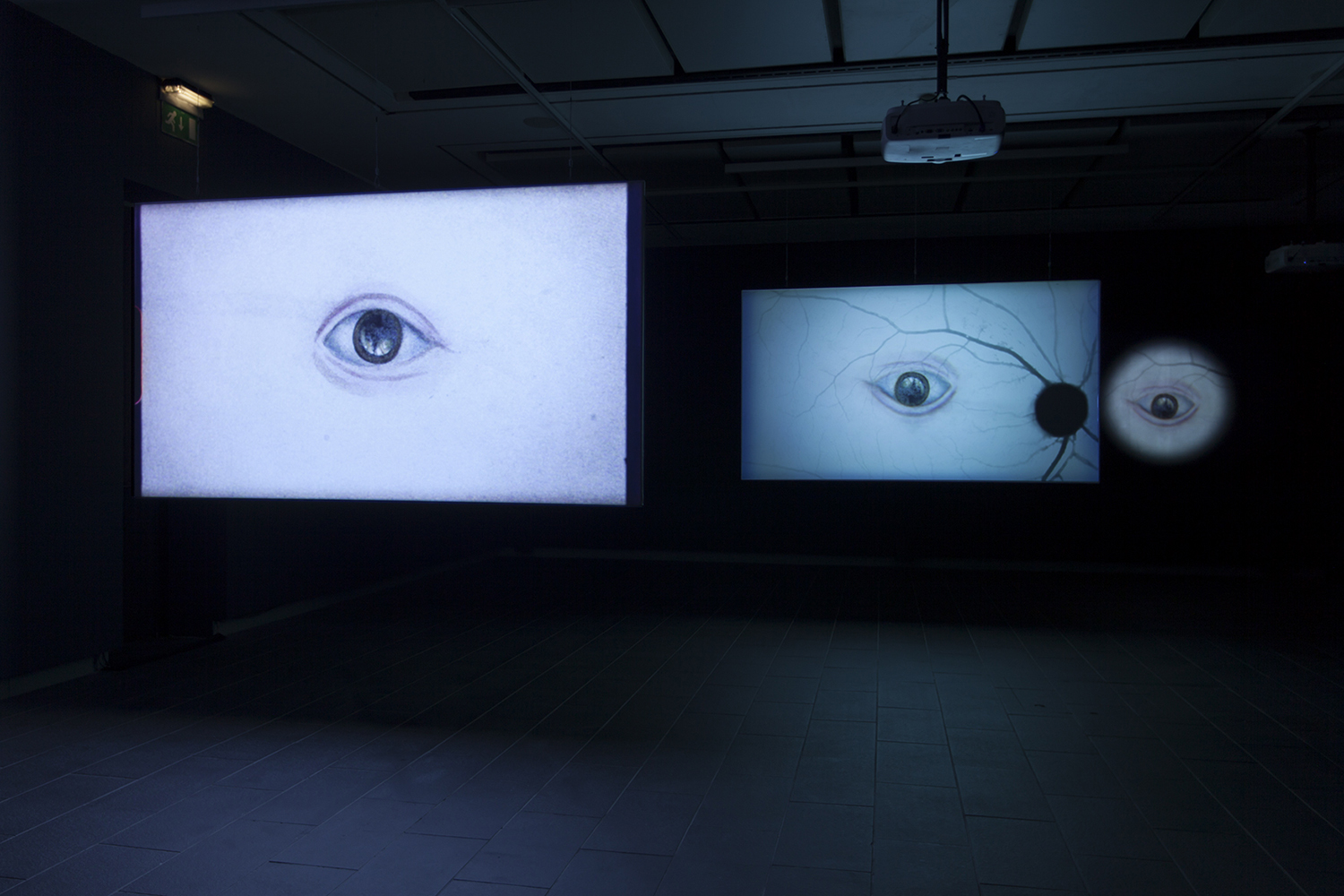

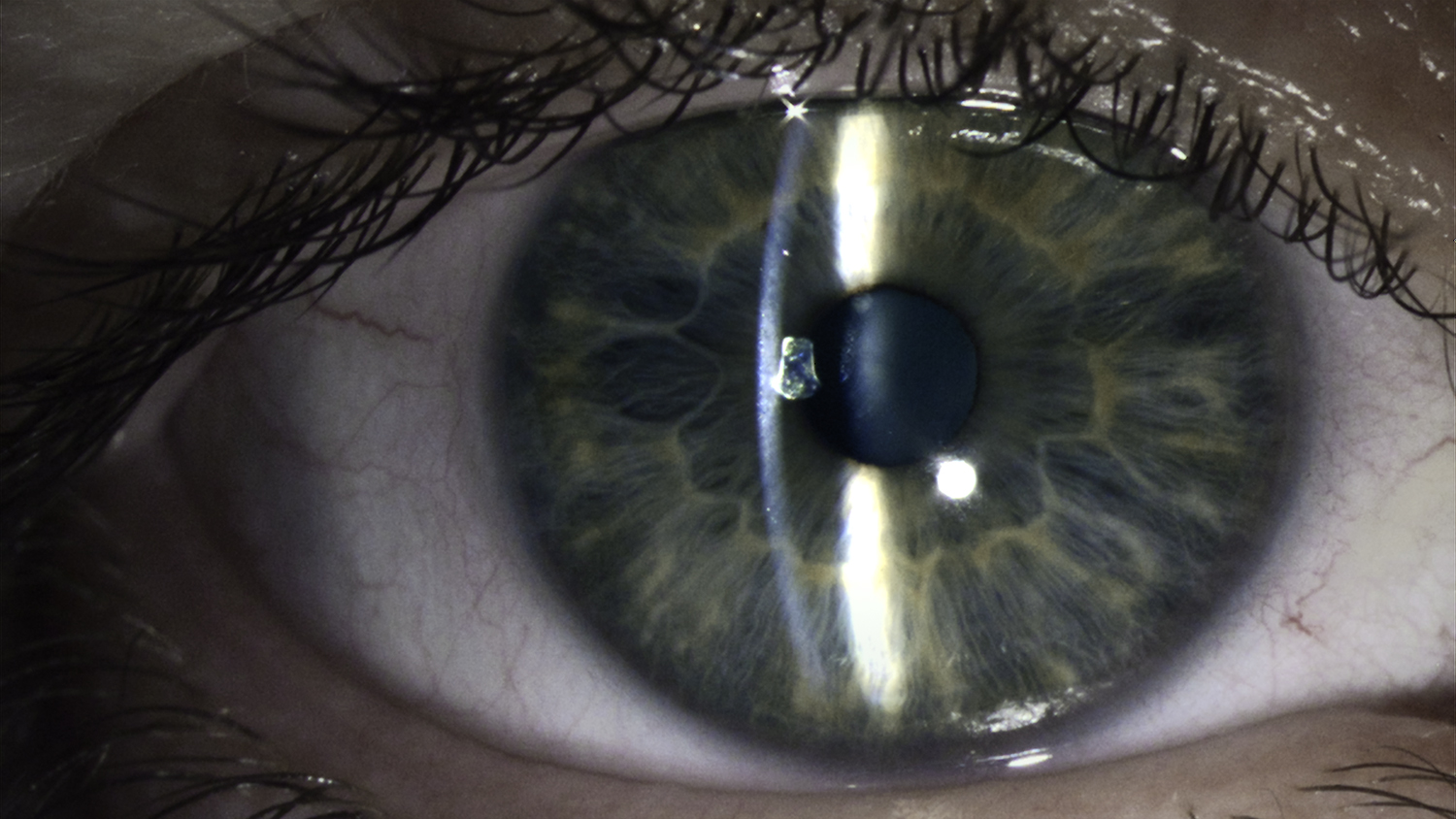

The touring solo exhibition by Hong Kong-born artist Suki Chan at the Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art (CFCCA), Manchester, contains only two video works. Lucida (2016) first debuted at Tintype Gallery in London, but at CFCCA, was shown in an expanded form on three suspended screens that made good use of the main gallery’s larger space and allowed visitors to walk around the piece to view from different angles. The other work on view, Lucida II (2017), was given its premier. For part of Lucida II, viewers observed an image of what appeared to be a cloudscape—there is a horizon formed by a bright stripe across the screen with ribbons of fluffy bubbling shapes in the lower half, and an inky upper half. The scene is hard to comprehend yet entrancing, the elevated viewpoint recalling 19th-century landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). It is only later that I learn this fantasy vista is actually a magnified scan of the retina of Suki Chan’s own eye. Heard through the first part of the video is a woman’s voice—belonging to the artist Annie Fennymore—that narrates the experience of gradually losing her sight. As the voiceover ends, the scene switches to a spectacular view of the night sky, moving from a personally focused subject to the cosmic, making the scene resonate as a poem to the sublime wonder of vision and the dread of its loss.

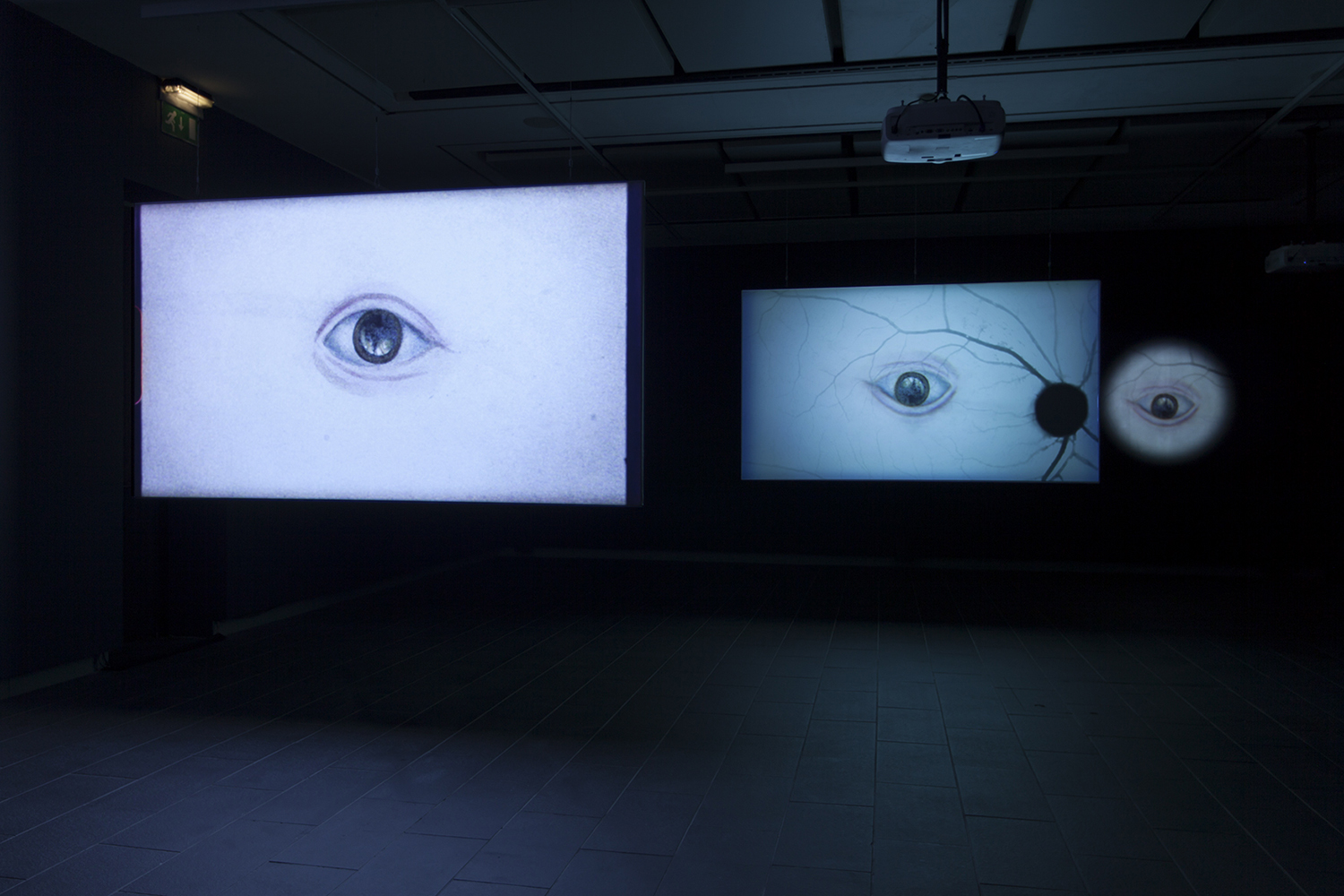

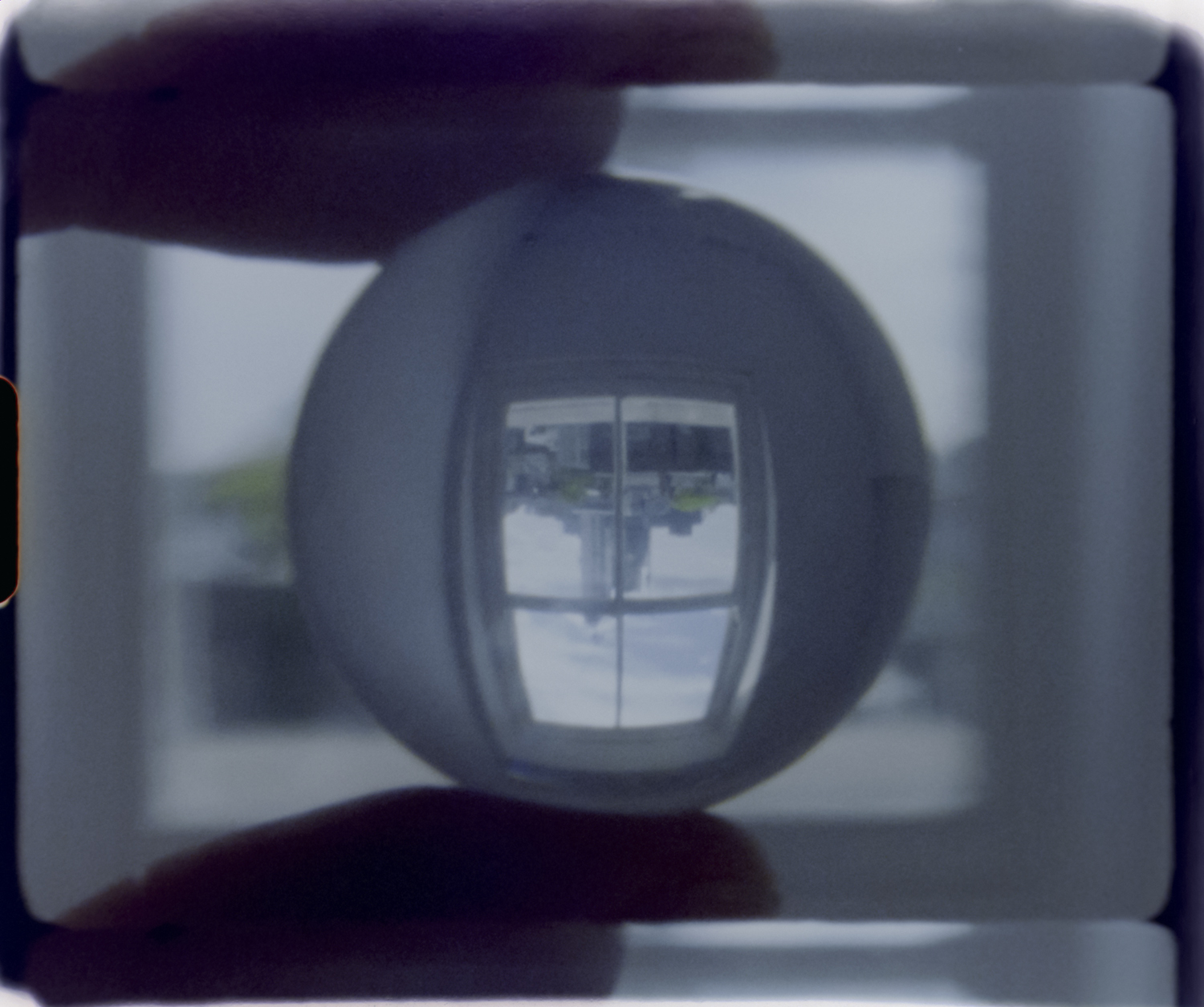

Subjectivity and the exploration of one’s place in the world are core topics in both videos. To fully activate both works, a viewer has to sit in a chair. By doing so, whoever occupies this position becomes part of the work for the other gallery visitors. Lucida and Lucida II both use an eye scanner to detect the movement of the eye, an experience that makes the participant very self-conscious. In Lucida, after the device records the eye movements, images of the retina and blind spot transfer onto the video screens. The presence of a participant in the chair also makes it possible to hear the soundtrack in which several scientists attempt to outline their current views on the mechanism of perception. There is tension between the dry, technical jargon and the lushness of Chan’s visuals. In the scientists’ discussion, a general model of perception is mapped out—sight is a constructive process from the brain attempting to impose order on an array of sensory input. Lucida includes a series of camera obscura experiments in which the artist simulates the raw visual data the eye receives with spectacular and hallucinatory results. In the film, Chan holds a glass sphere in front of the camera to illustrate the distorted and inverted image the brain learns to re-order.

The subtle implications of this hierarchical model are followed through in the work. Interwoven with the eye scans are scenes of an empty library and service corridors from London’s Senate House, an establishment founded by Jeremy Bentham, the creator of the panopticon—a design, originally for a prison, that allowed one guard to watch over all the inmates. The panopticon became an influential metaphor in Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975) for a self-disciplinary fear of being observed. The reference to the Senate House cues us to the political message of Chan’s work, which points to the fact that the very foundations of perception underlying the society of surveillance are unreliable.

Chan’s exhibition is enlightening and provides a history of the evolving theories of perception. Interaction with the video Lucida prompts a deeper consciousness from the participants, and a realization that their sight provides them a privileged position. Above the works’ thoughtful meditations on the mechanism of seeing, through its seamless blend of microscopic and cosmic imagery, Chan reminds us what a gift sight is.

Suki Chan’s “Lucida” is on view at Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art, Manchester, until April 30, 2017.