Shows

“Snail Fever” at The Third Line

“Snail Fever,” curated by independent curator Sara Mameni, is an interesting proposition that features visual artists who explore the realm of music and its awe-inspiring ability to go viral. The unusual, catchy title is inspired by bilharziasis, a type of parasite infection that killed legendary Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez in 1977, also known as “snail fever.” 1977 was a pivotal year in the history of modern Arab music, marking the end of the “Golden Age” that began in the 1940s. It also marked the beginning of the invasion of “Arab pop,” pop melodies infused with elements of various Arabic music styles, which has infiltrated the Arab world and its diaspora ever since. “Snail Fever” presents artists represented by The Third Line, including Abbas Akhavan, Ala Ebtekar and Slavs and Tatars, and fresher faces for the gallery, such as Fatima Al Qadiri and Khalid al Gharaballi, Haris Epaminonda, Christodoulos Panayiotou, Rayyane Tabet and Newsha Tavakolian.

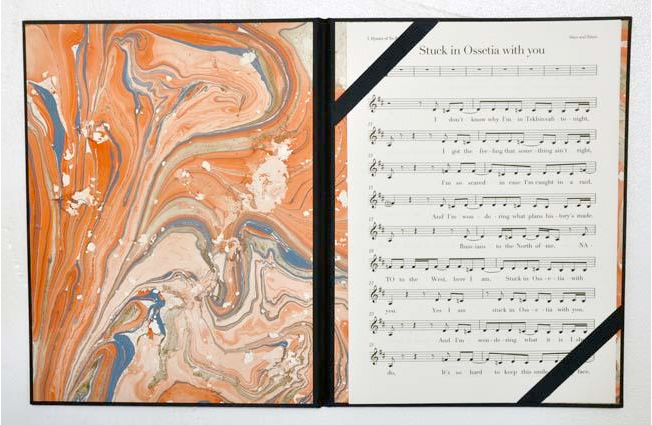

In true Slav and Tatars style, this artistic collective harnesses the power of language via Hymns of No Resistance (2010), by rewriting lyrics of Western pop songs to address political, historical, geographical and social issues within greater Eurasia. A piano score, laid out on a clear, rectangular glass table in the gallery space, states that it has been adapted from the Scottish rock band Stealers Wheel’s 1972 song “Stuck in the Middle with You,” and retitled, “Hymns of No Resistance (Stuck in Ossetia with You).” The reference to the Stealers Wheel song beguiles viewers to hum along to the familiar tune. It is easy, if not enjoyable, reading through the heady lyrics that provide witty, factual observations on the recent Russia-Georgia conflict: “Russians to the North of me / NATO to the West, here I am / Stuck in Ossetia with you.” Scattered thoughtfully amongst the lyrics are footnotes that further educate viewers on all things Ossetia, a region located in the Greater Caucasus Mountains that is divided into the Russian-controlled north, and the Georgian south.

The Adidas sneakers, boom box and paper flooring that make up American-born Iranian artist Ala Ebtekar’s floor piece, Electric Del Roba (2011) are aesthetically connected through different Iranian-Islamic motifs that adorn each of the individual pieces. The most eye-catching of the three is the boom box, covered in ornamental laminate that resembles geometric lacquering found on wooden, Iranian backgammon boards. Ebtekar’s intent is to create a hybrid style that speaks about music and its influences, combining 19th-century Iranian café culture from Tehran with American hip-hop. The American references are apparent, with the boom box and brand-name sneakers set up in a manner that evokes a street scene setup for break-dancing, while the allusion to Tehran café culture appears muddled. Perhaps it is in the Iranian backgammon board-esque laminate that is covering the boom box? While many of the pieces in this show hit the proverbial high note, Ebtekar falls flat—offering mundane observations on the obvious—yes, American pop culture has virally infiltrated into so-called “enemy nations” like Iran, albeit sanctions on American products.

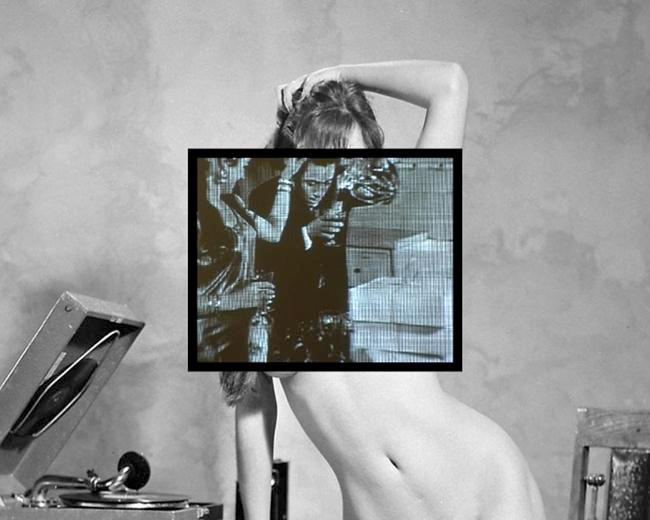

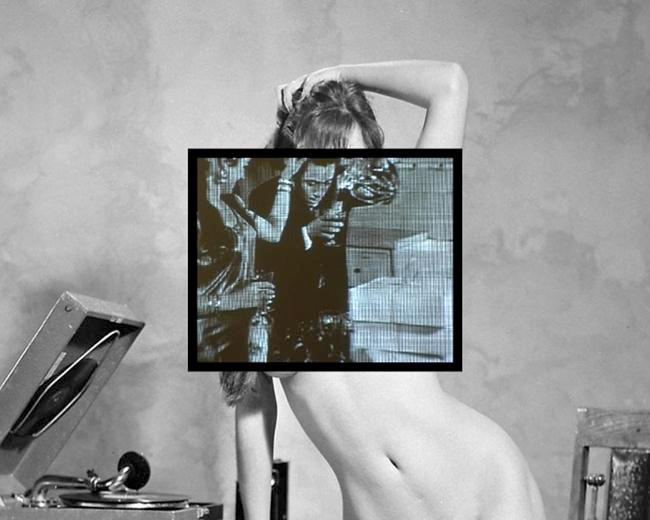

The most provoking work found in “Snail Fever” are the two photographs from Kuwaiti artists Fatima Al Qadiri and Khalid al Gharaballi, entitled WaWa Complex (2011) and Dala3 (in Vegas) (2011). The glossy photos, which appear as though right out of an MTV video still, address the rise of modern Arab female pop phenomena and its perpetuation of gender stereotypes. In these photos, the models and Al Qadiri [who is in Dala3 (In Vegas)] take on the persona of a lesbian couple, with models as the femme partner, portrayed as the ultimate fan girl-groupie, complete with coiffed hair and perfect makeup. Al Qadiri is dressed as the butch partner and takes on the voyeuristic role of licentious male consumer, appearing in Western garb and driving a red sports car in Dala3 (Vegas). In WaWa Complex, a male persona is adorned in local Gulf attire, and also wearing a baseball hat embroidered with “Kuwait”—a nod to the artists’ country of birth. Al Qadiri and al Gharlaballi’s photographs aim to address the lack of lesbian imagery in Arab society, shedding light on the culturally risqué subject in their artist statement and within the visual context of their work.

Moving away from fictitious musical icons, explored in the works of Al Qadiri and al Gharaballi, comes Lebanese artist Rayyanne Tabet’s elegant book, entitled Sherihan, Sherihan, Let Down Your Hair (Sherihan, Sherihan, Anzili Chaa’raki) (2011). The 25 handmade, white paper drawings, with Arabic lettering formed from stitches and pinholes, are presented unframed, and focus on two key events in the career of Sherihan, a famous Egyptian entertainer who is closely linked to the rise of modern Arab pop. Through rewriting the fairy tale of Rapunzel, by changing the protagonist’s name to Sherihan and incorporating her life-changing moments, a landmark photo shoot that put her on the map in 1976, and her contraction of salivary cancer in 2001, Sherihan—an iconic Arab public figure and voice—was transformed into a globally iconic children’s heroine.

While many of the artists in “Snail Fever” have commented on the universality of specific musical legends, icons and the socio-cultural branding that comes with the music industry, it is Vienna-based Cypriot artist Christodoulos Panayiotou’s dreamily romantic video piece, Slow Dance Marathon (2005), where random strangers dance to iconic love songs for a 24-hour period, which offers the broadest musical reflection of all. The tender embraces and sheer intimacy of random strangers rocking away to clichéd love songs attests to the universal ability that music has to transport and move us in ways unexplainable, even if it is just for an instant.