Shows

Slavs and Tatars’ “Long Legged Linguistics”

This summer, visitors taking the ferry from the Turkish resort town of Kuşadası to the port of Pythagorion on the Greek island of Samos, were greeted by a cryptic message, stenciled onto a modern white building in the harbor, that read ÖÖÖÖÖÖPS! The blue and green-outlined letters provoked immediate anxiety—had I made the wrong decision coming to the island? Why were there umlauts over the ‘o’s? Had I been pronouncing oops incorrectly for my whole life? Or was this some perverse joke about arriving from the bustling, lively shores of Turkey to a still-moribund Greece—the beautiful-sad country whose people have been led astray by misguided promises of prosperity with its entry into the European Union?

The piece—and its companion ωXXX (“ekh”) (2013), which means “oops” in Greek, on the building’s other side—perhaps responds to all of these queries at once. It also provides a thematic introduction to the collective Slavs and Tatar’s exhibition “Long Legged Linguistics” at Art Space Pythagorion. In its second year, the commodious summertime venue, which is supported by the Munich-based Schwarz Foundation that also runs a music festival on the island, is an enviable space in which to exhibit a single artist or collective. This exhibition, curated by Maria Fokidis, director of the Kunsthalle Athena, benefited from the non-urban, maritime location which inspired, or enriched, many of the works.

The phrase ÖÖÖÖÖÖPS!, facing the visible shores of Türkiye—just a couple of kilometers across the Aegean waters—jokingly references Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s infamous “language reform,” the first Turkish Republic’s founder’s attempt to modernize the Turkish language by adopting the Latin alphabet in place of Arabic script in 1928. Arabic, used in the Ottoman Empire, didn’t accommodate the range of vowels found in Turkish—in particular the vowel sounds “ö” and “ü”. Coming from Slavs and Tatars, who proclaim to “err on the side of darkies,” there was certainly a bit of lowbrow schadenfreude encrypted in their highbrow conceptual slogan, with its implicit nod to the blocky outlined fonts used by Lawrence Weiner.

The collective, whose self-declared geographical and historical purview is “the area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China,” have been on a language kick of late. Their publication and related installations in the project “Khhhhhhh” (2012) looked at the complex history of the “voiceless velar fricative” symbolized by [kh]—and heard in the letters X in Cyrillic, ḥāʼ (خ) in Arabic, and Ḥet (ח) in Hebrew.

Samos proved an ideal place the collective to explore their interests. For millennia, up until the population exchanges that concretized the modern nation-states of Turkey and Greece in the 20th century, the Aegean region was an incredibly diverse area populated by Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Slavs, Kurds and other peoples. This shared history led to linguistic heterogeneity and intermixing, with Turkic groups sometimes writing Turkish in Cyrillic letters and Greeks using Ottoman script. These are the sorts of cultural complexities that Slavs and Tatars relish in resurrecting, offering them as a rebuttal to the homogeneity of today’s more delineated societies.

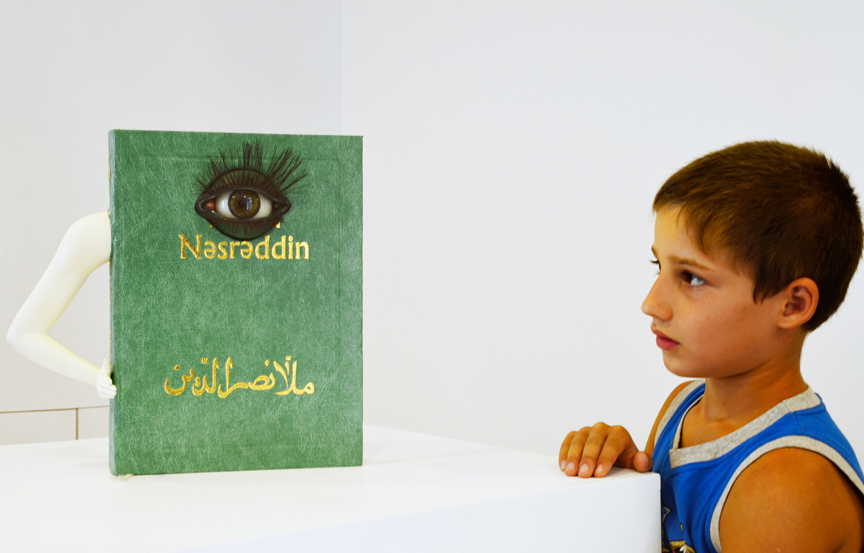

While Slavs and Tatars are concerned with such high-minded topics as “language politics” and “linguistic nationalism,” their investigations are heaped with ribald puns and disconcertingly campy humor through which they maintain their proclaimed “disengagement and nonpartisanship.” Upon entering Art Space Pythagorion, an oversized green book bears the gold-embossed title Nasreddin—as in Molla Nasreddin, the Muslim world’s favorite blundering hoja and comic dispenser of backwards wisdom, and a favorite subject of Slavs and Tatars. This pedestal piece, entitled Madame MMMorphologie (2013), has an arm protruding from one side and an embedded, long-lashed eye that periodically winked at you in a suggestive manner. Madame MMMorphologie set the tone for the collective’s new works on view in Samos, which together resembled something like a collaboration between a cocaine-addled Freud, an inebriated linguist and a senile, avaricious Salvador Dali.

Sounds are made with the mouth, and even if linguistics is an “unsexy science,” the orifice’s inherent eroticism was not overlooked. So proceeded a series of sculptures steeped in campy sexuality, each within a darkened room illuminated with overhead lighting. Qit Qat Qa (2013) is a silver-plated metallic “K”—referring to the phoneme [gh] and the Arabic letter qāf (ق), which is pronounced even further back in the mouth than [kh] and Latinized as either “K” or “Q” (as in “Koran” or “Quran”)—with a mannequin’s black-stockinged leg sticking out where the lower “leg” of the letter should have been.

In an adjacent room, Tongue Twist Her (2013) is a stripper’s pole, atop a purple-carpeted podium, around which is wrapped a gigantic serpentine tongue. On top of the metal pole, the glowing, translucent Other Peoples’ Prepositions is shaped like the preposition Ѿ—meaning “from” in Slavic languages—and resembles a pair of descended testicles. In these three works, and Madame MMMorphologie, the meeting of intellectualism and shameless punning resulted in works of a decisively vulgar appearance. The bumpy texture of the tongue revealed just how un-sexy the muscle is outside of the mouth. There’s a reason why sticking your tongue out at someone is considered rude.

There’s been an evident tone-shift in Slavs and Tatars’s practice in the last year, following their run of solo presentations at the Vienna Secession, MoMA and Künstlerhaus Stuttgart in 2013. The slightly older works, also on view at Pythagorion, showed more restraint. The wall-hung carpet Love Letters (2012) depicts an illustration by Bolshevik poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, of a figure emerging from inside the pages of a book surrounded by letters from Polish, Abkhaz, Moldovan, and Tajik—a reference to Lenin’s failed attempt to force the languages of several Muslim-majority provinces of the Soviet empire into Cyrillic in his “Revolution of the East.” A remake of a work shown last year at MoMA, Kitab Kebab (2013) consists of a metal kebab skewer that diagonally penetrates a series of books that Slavs and Tatars consider fundamental to their practice. Among them are the early Turkish novel Aşk-ı Memnu (“Forbidden Love”), Les Antimodernes by French literature scholar Antoine Compagnon and a German edition of Contemplation in a World of Action by the American mystic and interfaith scholar Thomas Merton. The diagonally placed kebab skewer supposedly symbolizes the transgression of “vertical” and “horizontal” forms of knowledge (in-depth specialty and broad general understanding, respectively).

Splayed out on an elevated platform in a separate gallery was Mother Tongues and Father Throats (2012), another rug (its industrial-produced texture doesn’t really merit it being called a “carpet”) several meters in length that features a diagram of where the Arabic letters are pronounced in the mouth. For this exhibition, Slavs and Tatars had added the letters for the guttural phonemes [gh] and [kh] in Cyrillic and Hebrew, in their words, “as a nod to these letters’ importance across such disparate fields as Russian Futurism, Kabbalist gematria, and Sufi literature.” Visitors were invited to to lounge on the rug’s surface to read the collective’s publications—though, frankly, the hard-surfaced, cushion-less, black-lit room held little appeal for either reading or conversing.

Lounging was more successfully encouraged in River Beds (2013), three wooden pavilions situated outside on the pier. Constructed in the style of takht, elevated sitting platforms common in Central Asia and Iran, with rahlé, wooden holders that are used to hold Qurans (Korans), these were being used by children and adults alike, some of whom had just emerged from swimming in the harbor. The simple structures are pleasantly devoid of punning or abstruse references, and were readily used by the public, some of whom were leafing through Slavs and Tatars’ publications—which remain the collective’s backbone and their greatest strength as artists.

Perhaps the most visually pleasing of the works—despite some low-tech plumbing and undoubtedly augmented by a view of the scenic bay—was Reverse Joy (2012), a small fountain spewing Kool-Aid-red liquid in the middle of a podium of ceramic tiles which bore the letters ḥāʼ (خ), Ḥet (ח) and the Cyrillic X linked by Mickey Mouse-gloved hands as if in a festive dance. For some, the red liquid reads as blood, but kids, according to Slavs and Tatars, tend to see something joyous and colorful.

Despite their commingling of references to different cultures and worldviews that in the real world are often in conflict, Slavs and Tatars are not politically naive. The collective treats all parties with mutual fascination and delight—and never with condescendence. It’s hard to think of other artists, especially those weighed down by partisan struggle, who manage this feat. Yet viewers should be wary of reading Slavs and Tatars’ search for the “authentic,” and their ability to appreciate the materials of diverse cultures, as “revolutionary” or suggestive of an “art of the future” providing “immediate access to a field of revolutionary politics”—as the philosopher Yoel Regev and artist Masha Shtutman have in a short, ludicrous essay, “The Children of Marx and Kumis,” in the show’s brochure. (The essay is better regarded as an anachronistic parody.) In reality, Slavs and Tatars are enrichers of the present, revealing artifacts of fascination that already exist in the world of histories and cultures that have been threatened by totalizing economic and political systems. It would be a shame to think of Slavs and Tatars as paving the way for a “truly materialist, revolutionary art,” as Regev and Shtutman do, for all that it implies about the erasure of the past and adopting a unified political dogma.

In most instances, however, Slavs and Tatars’ verbal packaging—phrases like “metaphysical splits,” “script charisma” or “redeeming the sensual”—is part of the fun (for adults and kids alike). Occasionally, though, it renders their objects more illustrative than as things to be enjoyed in themselves. This is particularly problematic in their sculptures that drift too far from being either quasi-functional, from referring directly to an appropriated aesthetic or from using unlikely materials—as was the case with both Tongue Twist Her, Other Peoples' Prepositions, and Qit Qat Qa, whose material and fabrication were unusually generic and lifeless. Slavs and Tatars' strength lies in their mining of materials and forms steeped in tradition and making them into hybrid ancient-futuristic creations. They shouldn’t forget that just as spoken and written languages contain resonances of cultural, historical and political events, so do the materials and methods of art-making. The pleasures of things are manifold, even if they are usually unspoken.