Shows

“Shuimo Water Ink: Chinese Contemporary Ink Paintings”

The selling exhibition “Shuimo Water Ink: Chinese Contemporary Ink Paintings,” curated by Mee-Seen Loong at Sotheby’s in New York, demonstrated once again the versatility and power of art made with the simplest of materials and the most refined and complex techniques. The works ranged from soaring, meticulous Song-style landscapes to confrontational abstractions achieved with the single thrust of a large, wet brush. But the show had less to do with traditional, scholarly self-effacement or Modernist iconoclasm, and more to do with acts of personal expression.

For example, color is used in non-traditional ways in Li Huayi’s Whispering Pine, Reaching to the Clouds (2012), a vast white-to-grey mountain landscape depicted from a vertiginous angle, with the twisting pine of the title “colorized.” Whereas the tree executed in blacks and grey would naturally attract the eye, the addition of color adds a touch of surprise to the work, much louder than a whisper.

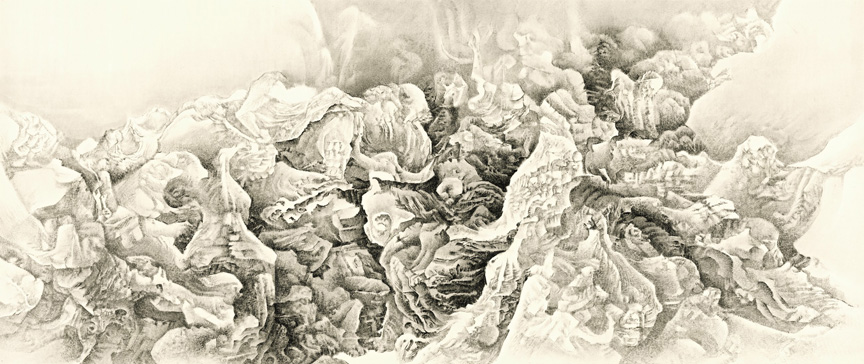

Color was not used in the dense, convoluted, near-terrifying landscapes of Tai Xiangzhou. Tai’s lengthy calligraphic colophons, in skillful regular script, demonstrate the artist's respect for his classical heritage. At the other extreme, color bursts across the comical expressionist works of Li Jin, with their overt social criticism.

Abstraction in a traditional mode might describe the works of American born Arnold Chang—in which elements familiar in Chinese landscape painting appear to be distorted and displaced in a fresh and modern way—yet his scrolls still bear the stamp of the refined scholar-intellectual. Similarly, Liu Dan’s large Silent Mountains, Meandering Paths (2013) delights and disarms the eye with its ambiguous confusion and blending of clouds and mountains.

Scholarly fondness for the grotesque is stretched to the limits by Zeng Xiaojun, whose Wild Spirit Screen (2012) is a haunting depiction of a psychedelic, surrealistic plant form—an uprooted tree of sorts with stark intertwined branches, odd root systems, unnatural growths and spooky crevices. Call it Chinese Gothic, if you please.

In technical terms, the collages by the Master of the Water, Pine and Stone Retreat, are unique in this exhibition in a couple of ways. First, the inscriptions are in English, the native language of the British artist. Second, the subject matter—or more precisely, the ink on the paper—is applied in the form of collage. The Master first paints traditional landscape elements on “cloud-dragon paper” and then cuts out sections of this material to paste on the finished work. The trompe l’oeil effect is entirely convincing. In The Eight Sainted Staves (2012), eight separate scrolls each depict a walking stick accompanied by a long text in a faux-literary Chinese style about the artist’s encounter with the “Chisel-Immortal,” the artisan to whom the artist attributes the creation of the staves. With (British) tongue firmly in (Chinese) cheek, these works raise intriguing questions about Chinese art and identity.

“Water Ink,” one of Sotheby’s first selling exhibitions of Asian art, set off a small controversy over the issue of a major auction house stepping on the toes of individual galleries and dealers with fewer resources. But there are more factors than the obvious commercial ones at play here, and it is hoped that the incident will remain a storm in an inkpot.

Don J. Cohn is senior editor of ArtAsiaPacific.