Shows

Shen Xin’s Theater of Verbal Imagery

Can the image of Tibet truly be disassociated from settled worlds and monumental histories? Shen Xin’s “ས་གཞི་སྔོན་པོ་འགྱུར། (The Earth Turned Green)” was an undaunted attempt to conjure up a new image of Tibet: one based on the shifting realms of intersubjective relationships and intermedia translations.

Presented by the Swiss Institute in New York, Shen’s solo exhibition consisted of a silent video that depicts the choreography of light and shade on an empty theater stage. Within the static video frame, the indoor theatrical space is transformed into an abstract landscape with the wall and the floor as the sky and the earth, tinted in endless chromatic combinations. To create this footage, Shen worked with lighting technician Kyle Gavell to simulate the daylight from each of the four seasons with the theater lights. What the lighting partly illuminates is the glaring absence of performers and imageries.

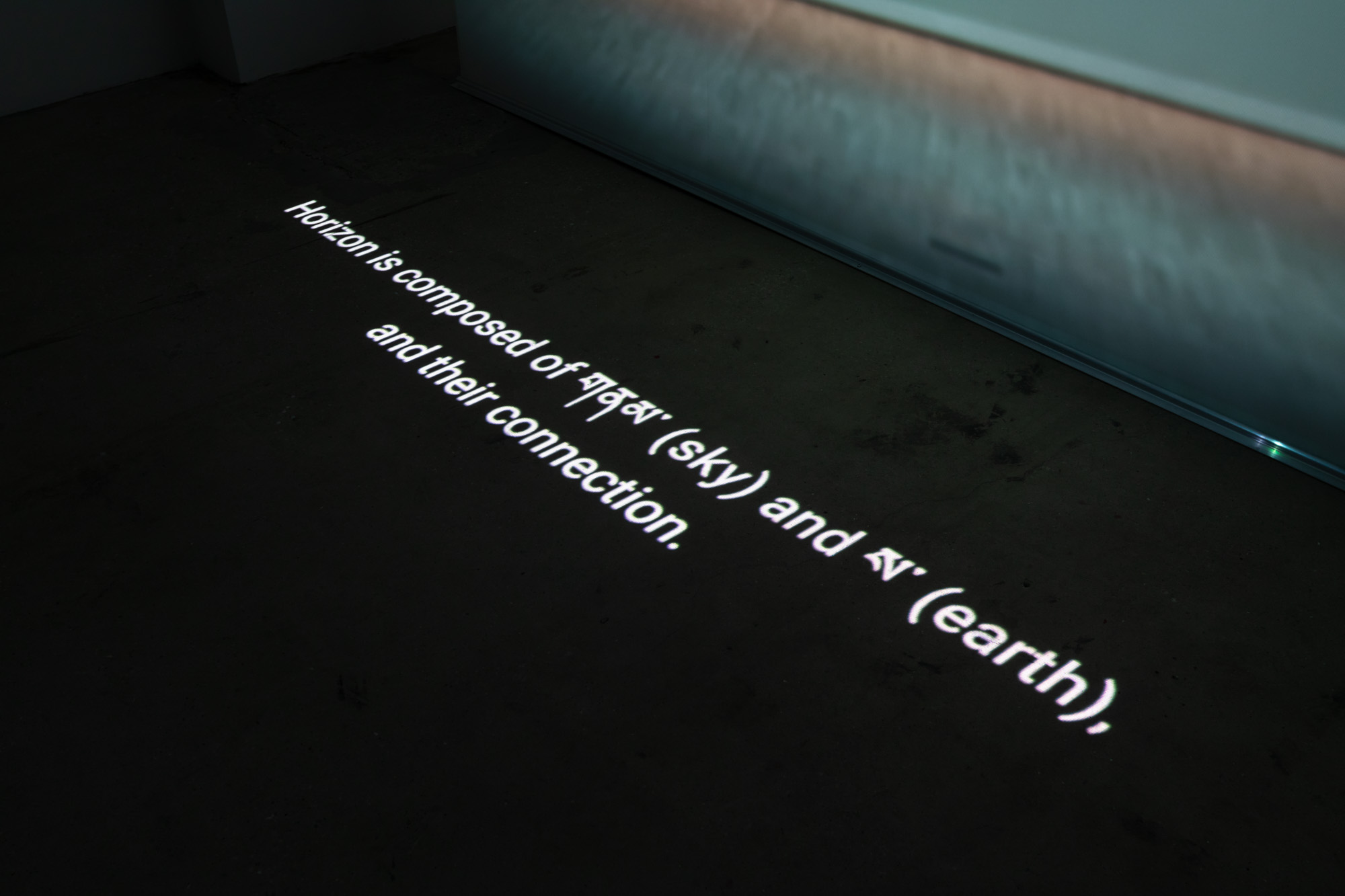

The video was projected on either side of a screen that divided the Swiss Institute’s dark room into two viewing spaces—one with English subtitles cast on the floor, the other with Tibetan. The English subtitles match the 39-minute audio recording of the conversations between Shen and their Tibetan language teacher སྐྱིད་དར་འཛོམས། (Ji Ta Zong) during their lessons. The Tibetan subtitles, however, are not synchronized with the audio that resounds across the viewing spaces. They are Ji’s translation of the descriptions that Shen wrote in Chinese about Gavell’s lighting effects, which later served as the text for their lessons. Unlike conventional onscreen multilingual subtitles that presume a diverse and collective spectatorship, Shen’s offscreen subtitles did not so much facilitate Tibetan audiences as they foregrounded the uneven attendance across the linguistic boundary.

These absences—of visual representations of Tibetan people and of Tibetan audiences—are at the core of the exhibition. The artist resists the overproduced, oversaturated images of Tibet as the exotic other for both ethnic majority Chinese and the West. The spatial, linguistic, and visual divides in the exhibition pointed to not only ethnic segregation but also interrupted genealogies. Shen’s father was a non-Tibetan painter of Tibetan portraits. Critical of their father’s practices while he was alive, Shen discovered only after his passing that he was genetically part-Tibetan. The new-found knowledge destabilized Shen’s ideas of belonging.

This discovery also destabilized a dominant historiography of art that insidiously mediated the father-child relation. It is often contrived that Chinese contemporary art began after the negation of socialist realism, including its post-socialist remnants like the realist “native soil paintings,” for which the Tibetan minority was one of the most representative subjects. This narrative of disruption, told from the perspective of art centers like Beijing, obscures the lived experiences of local art practitioners and actual encounters in Sichuan, a multiethnic borderland and where the Shen family resided. Yet Shen’s endeavor to restore vast geographic and historical fractures does not follow a straight path of “root-seeking,” which was what motivated the native soil movement in the 1980s. In a way, to connect with the elder generation’s practice is also to inherit the failed project of replacing one monumental history with another.

Refraining from any existing grand narratives or images that could again essentialize ethnic differences, Shen invited audiences to venture into the interlocutory dynamics between Tibetan and Mandarin Chinese speaking voices. A laborious process of medial and linguistic translations turns the language-learning practice into lively exchanges of metaphysical contemplations. Shen and Ji explore how, in the Tibetan language, the perception of color is inherently entangled with temperature; how “sky” is both spatial and temporal; and how the expression of “becoming brighter” involves the ideas of a bird, a path, and fire. This seemingly minimalist work severs and reassembles a diverse range of senses in order to synthesize a new theater of verbal images. As a result, the screening room, including its spaces of absences, is filled with a colloquial, embodied, and relational presence that disseminates across text and image, nature and convention, and distance and duration.

Shen Xin’s “ས་གཞི་སྔོན་པོ་འགྱུར། (The Earth Turned Green)” was on view at the Swiss Institute, New York, from May 4 to August 28, 2022.