Shows

Seventy Years of Self

There are myriad Yayoi Kusamas; there is only one Yayoi Kusama. The many conceptions of self and selfhood run through the entirety of the iconic artist’s turbulent life and diverse creative output from, as the M+ retrospective is titled, “1945 to Now.” Across more than 200 paintings, drawings, installations, sculptures, videos, and printed emphera, we encounter these many figures, from Kusama the abstract painter to Kusama the performance artist, and in her many affects, from charismatic to obsessive, depressive, and, ultimately, in her 80s and 90s, a self-professed lover of life itself.

An archetypal midcentury artistic figure who left her home in Matsumoto, Japan, to find creative freedom and new experiences in the artistic center of the time—New York, from 1958 to 1973, in her case—Kusama embodies “the century of the self” with the chaotic giddiness of a media-driven consumer society and the concomitant sense of alienation and anxiety. Yet no matter where she lived or what cultural influences she absorbed, Yayoi is Kusama’s ultimate subject: her painful early life experiences during and after the war; her ambitions as an artist; her struggles with hallucinations and mental illness; and ultimately, as a creative being who found in the act of art-making a method of coping with her fears and obsessions.

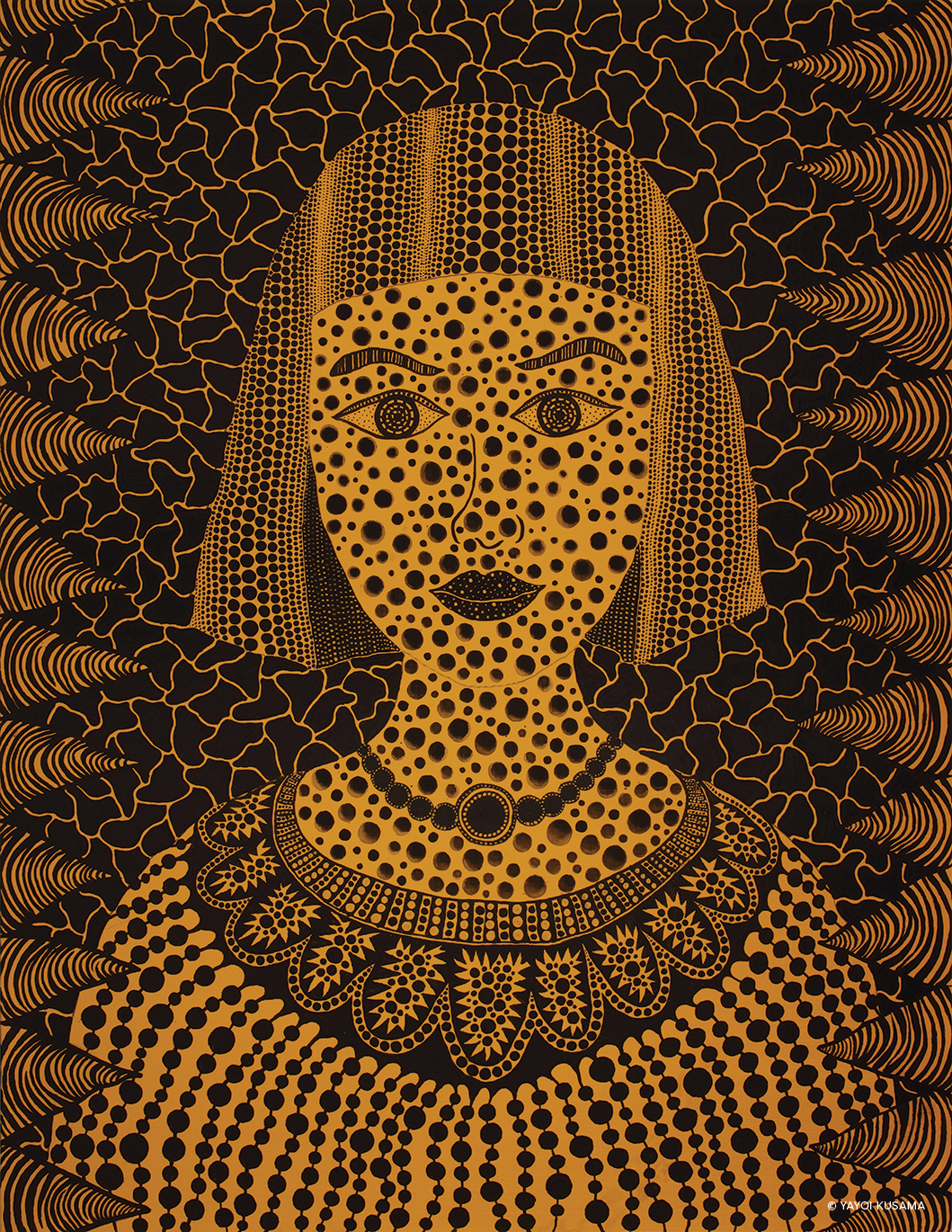

Emphasizing the centrality of self, the exhibition begins with a gold and black self-portrait from 2015—a deceptively cogent depiction of her short wig, face, and upper torso amid a patterned field of lines, dots, and squiggles. Co-curators Doryun Chong and Mika Yoshitake quickly dismantle any stable sense of “Yayoi Kusama,” however, with an adjacent wall of 11 more self portraits from 1950 to 2020 that take forms from the abstract to the vegetal to the cartoonish. The self in these representations is raw, primal, protean, even grotesque—more id than ego, more animal and plant than human. Like Narcissus transformed into a garden of tiny flowers, Kusama the disappearing is another one of her manifold selves.

“Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now” is organized thematically around six key concepts in the artist’s oeuvre, with chronological narratives built within each. The first of these themes, “Infinity,” elaborates on how her obsession with dots grew out of her “infinity net” paintings. The section chapter begins with a small, abstract painting with a coral-like pattern, The Sea (1958), before presenting Pacific Ocean (1959), a diptych covered in a web of white arcs of paint, inspired by her experience of flying from Japan to the United States and looking down at the water. These early forays into the abstract yielded six more decades of experimentation, revealing her compulsion for obsessive making, her desire for self-obliteration in vast fields of color, and how her webs and dots—the literal positives and negative spaces of her imagery—were fundamentally interconnected in her personal cosmology. The M+ exhibition doesn’t explicitly delve into the postwar context of abstract painting, but if you can imagine Kusama arriving in New York at a moment when large-scale abstract painting was the most celebrated form of art-making, her “all-over” approach to painting takes on a feminist bent, as she attempted to challenge the male-dominated scene. Her first solo exhibition in New York, at Stephen Radich Gallery in 1961, featured a ten-meter-long infinity net painting: her most robust effort to be Kusama the New York school painter.

A friend and studio neighbor of Eva Hesse, another female artist pushing back against masculine forms of abstraction, Kusama as a post-minimalist sculptor was foregrounded in the “Accumulations” section. Her “soft” fabric sculptures covered in clusters of yam-sized fabric sacs (she called them phalluses) painted white or silver—including the covered armchair Accumulation No. 1 (1962), plus shoes, a dress, a ladder, and a mannequin—give a lurid sexualization to these domestic commodities and window-display items. The fabric Accumulation works metaphorsed over time into more biological forms, and ulimately led to the 8.4 meter long, 3.4 meter tall installation of silver-painted boxes filled with hand-sewn tubular forms, Shooting Stars (1992), which she displayed in a solo presentation in the Japan Pavilion at the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993. For an exhibition at the Fuji Television Gallery in 1986, psychoanalyst Félix Guattari praised Kusama’s search for “the germinal state of the world,” calling her works “explorations of vegetal and vegetative virtualities which haunt our subjectivity.”

In both attitude and form, Pop Art and “happenings” (non-theatrical, performance events) were two modalities that disrupted the hegemony of abstract painting in mid-1960s New York City. Kusama, as a denizen of the downtown counter-culture scene, imbibed those influences and melded them with her dot obsession into her installations. This is evident in the installation Self-Obliteration (1966–74), which features six female mannequins, a dining table, and chairs all covered in her nets paintings on a bed of dried pasta (another of her phobias). “Polka dots can’t stay alone. When we obliterate nature and our bodies with polka dots we become part of the unity of our environments,” she famously commented. This idea of disappearing into a field of dots was a product of her hallucinations, but also relates to Kusama’s interest in self-obliteration of the ego, an embrace of nothingness, and what the curators call her “radical connectivity.”

In the social sphere, her forms of radical connectivity encompassed the liberation of the individual through collective events and her engagement with mass media. As forms of social protest Kusama invited her friends to strip naked and let her paint on them, and join her in her mirrored installations, where events turned orgiastic. These “Body Festivals,” as she called them amid the “free love” atmosphere of the late 1960s, were captured in photographs and films including one by Jud Yakult. Her anti-war activism culminated most notoriously on August 24, 1969, with an occupation of the Museum of Modern Art’s sculpture courtyard, called “Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead at MoMA (Otherwise Known as the Museum of Modern Art)—Featuring Their Usual Display of Nudes,” an image of which ended up on the front page of the Daily News. Capturing the attention of the media and popular culture has long been one of Kusama’s skills, as the collection of archival materials at M+ reveals.

The “Biocosmic” section illustrated Kusama’s lifelong obsession with organic forms. Her parents ran a nursery in the mountainous Matsumoto region, and in her earliest sketch books she made beautifully detailed pencil drawings of dead leaves and flowers. An early adopter of surrealistic styles in Japan, her “biomorphic” paintings of the early 1950s resemble microscopic views of cells; in the late 1970s she paints flowers in the shikishi-style of watercolor paintings. Here, Kusama’s “radical connectivity” bridges the human-made and natural worlds, as in the five standing, dotted flower sculptures (three sprouting pollen-like strands of synthetic fiber; two closed up for the night) from 1985–86, a nearly five-meter long stuffed-fabric Red Flower (1980), the slithering mass of yellow and yellow-dotted tangle of roots, Sex Obsession (1992), and a set of six small Pumpkins (1998–2000).

Connecting together all the Kusamas is the section on “Death,” where we see Kusama wrestling with the impacts of the war in the early 1950s in paintings such Accumulation of the Corpses (1950), featuring a twisted-root or rope-like abstract form in a landscape marked by a line of barbed wire, and again in the blood-red vortext Accumulation of the Corpses (Prisoner Surrounded by the Curtain of Depersonalization) (1950). The installation Death of a Nerve (1976) of colorless, black-dotted stuffed fabric strands was made at the height of Kusama’s depression after her return to Japan in the 1970s and following the passing of her friend Joseph Cornell and her parents. Forms once full of life become symbols of lifelessness: her stuffed silver phalluses frame A Gateway to Hell (1974), in one ceramic work, and a large wall sculpture with silver branches, Prisoner’s Door (1994), is uncannily reminiscent of Auguste Rodin’s tangled figures in his Gates to Hell (1880–1917).

“Could I keep living? / I will ask my art,” she wrote in her 2006 poem, “A Message of Love From Yayoi Kusama.” From “Death” emerges the resurgent Kusama in “Force of Life,” a gathering of recent series that focus on the curative, life-affirming aspects of her late work—not only for herself but “for the healing of all [hu]mankind.” Curators selected 30 of the large, brightly colored canvases from the more than 900 canvases of the “My Eternal Soul” series (2009–21). Distinctive in their colors and motifs, they are filled with heads, eyes, animals, amoebas, and abstract forms, bearing titles like There Is No One Who Is Unmoved by How Amazing It Is to be Able to See the Beauty of Creation Everyday in This World and Universe We Live In and Splendour of the Great Blue Atmosphere That the Lake Creates (both 2019) that radiate Kusama’s joy in creation, which continues to this day.

Once you’ve had your comprehensive education in the many Kusamas, the hanging fabric installation in the M+ Lightwell atrium, a colorful re-make of her 1976 suicide contemplation sculpture, Death of Nerves (2022), and the pair of giant yellow pumpkins in the lobby, with their references to wartime famine, appear less cloyingly cute. The Studio space at M+ hosts the Dots Obsession—Aspiring to Heaven’s Love (2022), a black environment with giant inflated balloons covered in white dots with a mirrored cube “infinity room,” where in your allotted 90 seconds for selfie-taking you can instead try to lose yourself in the world of dots—Kusama’s most experiential approximations of her mental state. Briefly, you and your many selves can feel obliterated by the Kusamian cosmos.

“Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now” is on view at M+ until May 14, 2023.

HG Masters is ArtAsiaPacific’s deputy editor and deputy publisher.