Shows

“Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping”: Finding Respite in Candice Lin’s Cat-Demon World

In Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson writes, “[w]hen the prevailing notion of (human) being becomes synonymous with ‘universal humanity’ or ‘the human’. . . this is an outcome of power, whereby one worldview is able to supplant another onto-epistemological system with a different set of ethical possibilities. The more ‘the human’ declares itself ‘universal,’ the more it imposes itself and attempts to crowd out correspondence across the fabric of being and competing conceptions of being.” That is, to search for reimaginings of beingness beyond the category of the human is to search for other worldings, ways of knowing, and existences that thrive and unsettle the granted authorities that are responsible for the social inequalities of the status quo. Taking on this critique against liberal humanism, whose logics are rooted in the notion of sequestering some communities (racialized, queer, gendered, etc.) from being granted humanity and power, might additionally entail confronting our entangled relationships to the spiritual, the microbial, and the animal worlds in nonhierarchical ways. It is through this entanglement that Candice Lin’s recent solo exhibition exemplified a commentary on “the human” as a hegemonic category.

“Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping,” which opened at the Walker Art Center in August, centered a large tent structure whose roof was constructed of hand-dyed indigo fabric panels. The textiles feature compounding hand-drawn and printed images in rice-resist paste that reference Western and Eastern iconography (multi-eyed cats, the Roman she-wolf, Egyptian sphinxes), as well as contemporary popular culture. The poles are decorated with statues modeled after zhenmushou figures, each taking on a different appearance: some are composed of modular ceramic cylinders, adorned with wire crowns that are entwined with strips of fabric, beads, and miniature found objects; some have protruding limbs and fanged faces with bright red tongues; others are sculpted into bearded quadrupeds with six breasts. Under the tent, there is an assortment of cat-shaped clay headrests and a small television that plays an animation narrated by a cat named White-n-Gray. To sit among these quasi-spiritual guardians transported visitors into a haven for contemplation, and—as the title suggests—resting and weeping.

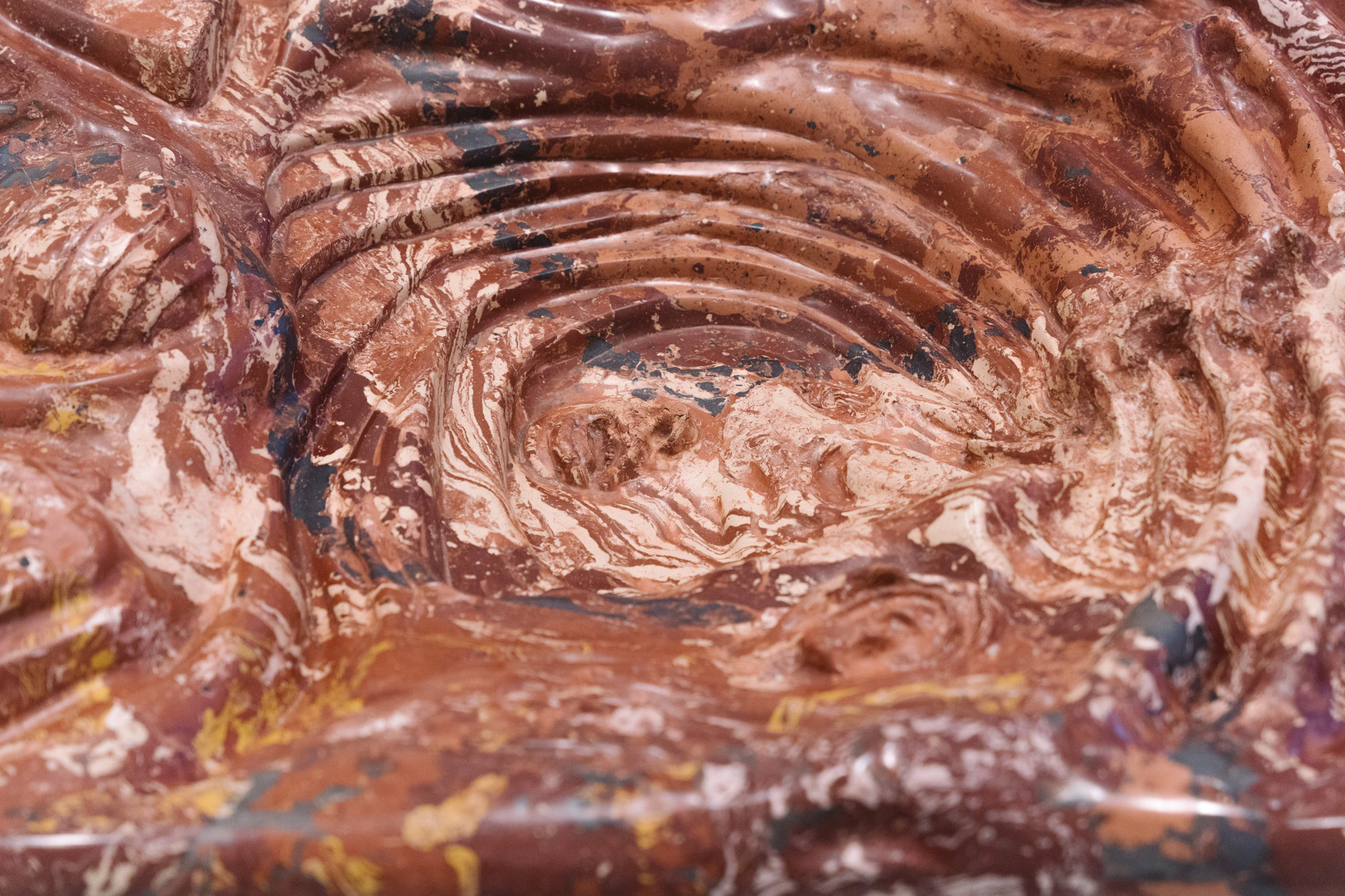

Constructed during a period of intense socio-political unrest in the United States, further heightened by the Covid-19 pandemic, the installation cultivates a sensuous relationship between human and nonhuman beings through touch. The nonhuman is embodied by not only the animal- and demon-like figures, but also the fermentation of indigo, which necessitated a symbiotic relationship with microbes. The tent was also accompanied by Tactile Theatre #1 (after Noguchi) and Tactile Theatre #2 (after Švankmajer) (both 2021), two molded slabs of concrete and plaster, respectively, that resemble a valley of body parts. On another wall, Millifree Work Weary Free ™Video (2021) projects an animated cat-demon with enlarged mammae, postured to lead a peaceful qigong exercise. The routine begins with a gentle voice and binaural beats, yet is periodically interrupted by spambot messages, viral video clips, and loud audio clips of songs by Dengue Fever, who combine popular 1960s Cambodian music with psychedelic rock. Through tactility, and in the guise of play, Lin’s show encouraged people to build a sense of intimacy with a variegated and nonhuman world.

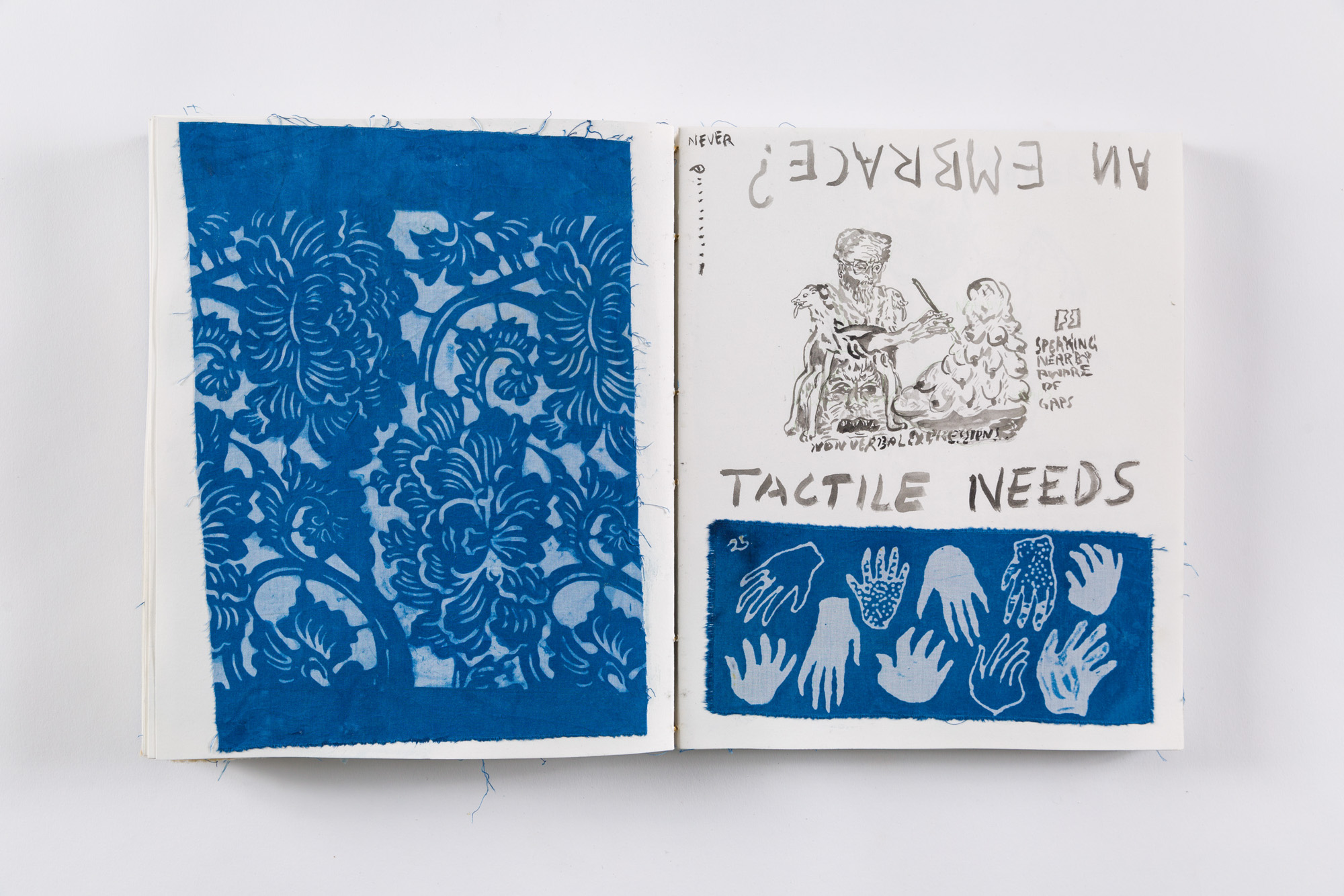

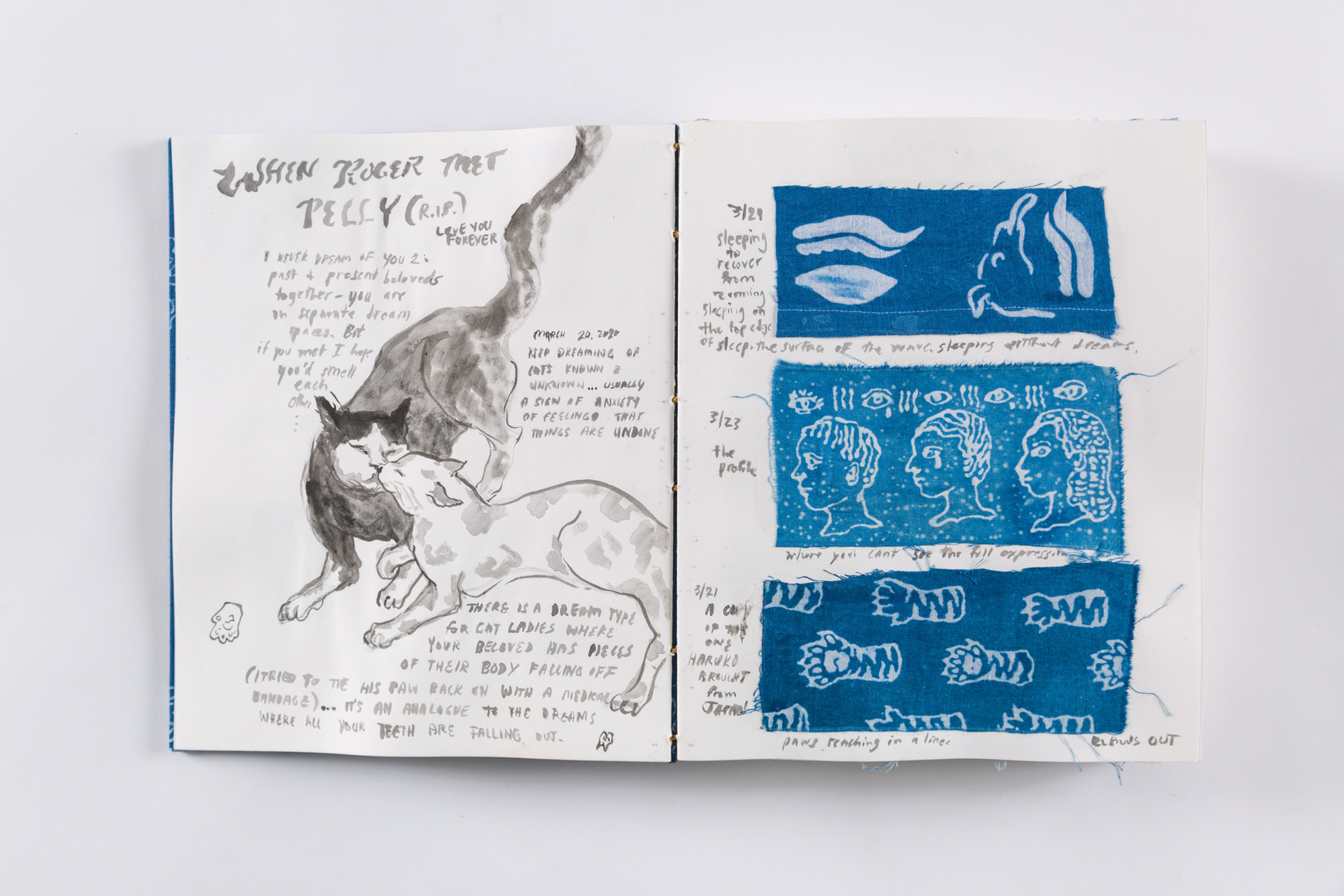

The show’s most critical piece was Lin’s Journal of the Plague Year (Cat Demon Diary) (2021), which was placed on a pedestal next to the tent. Visitors could flip through (with gloves) Lin’s pandemic sketchbook, which was used to archive swatches from dyeing experiments, and to recollect the days’ events, from the artist’s challenge of combating the rats that were eating through her rice-resist paste to responses to anti-Asian and anti-Black violence.

The most notable absence was that the show hardly raised the question of how indigo, beautiful in its hues, has a dark history as a colonial cash crop. In fact, this trepidation to recite the ways in which indigo relied on enslaved and indentured labor is noted by the way the exhibition subtly offered “A Brief History of Indigo Dye and Techniques,” which could only be accessed through a QR code. Thus, while the installation was successful in establishing playfulness, the show’s overall obfuscation of indigo’s coloniality and the city’s ongoing struggle with the Minneapolis Police Department’s systemic racism and abuse made negligible Lin’s references to the past year’s uprisings, such as “ABOLISH POLICE,” which was cleverly embedded in some of the block print patterns. This cat-demon world built upon the entanglement of human and nonhuman, but it belied the crucial contexts that necessitate the foregrounding of this entanglement in the first place.

Candice Lin’s “Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping” was on view at the Walker Art Center from August 5, 2021 to January 2, 2022.