Shows

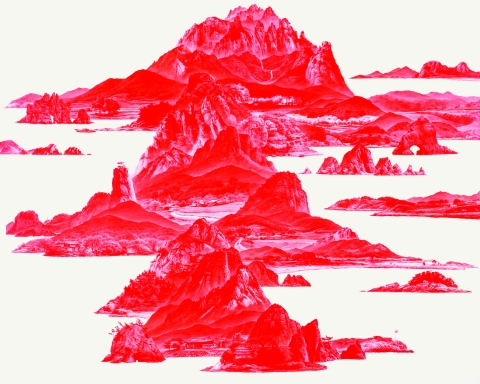

SeaHyun Lee’s ”Between Red”

At first glance, South Korean artist SeaHyun Lee’s finely painted, red-on-white realist landscapes may seem to illustrate scenes from a timeless utopia. A pagoda or two can be spotted amid massy peaks. Yet pools of blankness, floating terrains and improbable perspectives attest to something amiss, while the odd watchtower or warship, initially inconspicuous, suddenly triggers a sense of history. Drawn from Lee’s memories of military service, when he surveyed the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) at night through infrared goggles, these paintings have the singed, spectral quality of discolored film stock or retinal afterimage. Their fragmentary visions conjure a lost natural world, untouched by urban development, and speak to the yearning for an undivided Korea. Marking Lee’s US solo debut, this exhibition showcases ten works from his “Between Red” series, each of which rearranges those fragments into a different composition.

Lee’s monochrome palette taps into a variety of associations, such as pastoral toile patterns or American painter Mark Tansey’s tinted, post-modern allegories. The choice of bright, cinnabar-seal red carries a sharper emotional charge: wondrously aglow yet chillingly insistent, the color evokes Communism’s tumultuous role in Korean history. Though mistakable for bare linen, the negative spaces in these paintings are meticulously painted in white, with clean edges that imply precise effacement instead of fuzzy recall. Rocks jut out of emptiness like dorsal fins in a calm seascape. Promontories look as though they could have been plopped onto the canvas from intricate cake molds.

At times, Lee pieces together disparate sites at incompatible scales, producing a photo-collaged effect. In Between Red 113 (2010), for instance, a dim corridor abuts a mountain vista, which in turn borders a foreshortened tract of farmland. In other works, modules of landscape are arranged into voluminous enclosures or parallel peninsulas, as seen in 111 (2010), 049 and 060 (both 2008). Certain motifs obsessively recur, such as a rock arch, plowed fields, an industrial power plant and a dragon-prow ship. Gathered into the same pictorial plane, elements of human history are thus juxtaposed with those of natural history. Moreover, some viewers would recognize that particular ship as the Turtle Ship, a legendary Korean navy vessel credited with defeating a Japanese invasion in the 16th century, and a potent national symbol ever since.

Lee’s layering of asynchronous temporalities may stir up popular imaginings of the DMZ (and of North Korea) as an apocalyptic Cold War abstraction. But what these paintings mainly depict are obdurate landforms, reduced habitation and sparse means of subsistence. No people are visible, although there are quiet signs of life, like a farmhouse in snow and lights along a shore. Scarred by landmines and abandoned tunnels, and lately grown wild into an accidental nature preserve, the DMZ is both a gash and a ligature—touching both Koreas, home to neither. Lee’s beguiling, uncanny paintings force us to contemplate that sundering yet shared geography.