Shows

Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s “Sugar”

Stemming from Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s own matrilineal history of indentured servitude in the former province of Natal—now known as KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa—“Sugar” at Milani Gallery, Brisbane, continues the artist’s interrogations into the labor of indentured workers, here tending to that of sugarcane plantations held by the British Empire. As a part of Europe’s vast colonial project across the 19th century, over a million Indians were forced to enter indentured servitude for Dutch, French, and English colonies as a way for each empire to skirt around the newfound abolition of slavery throughout Europe. Derogatorily referred to as “coolies,” these people collected pittance pay for their labor, worked gruelling hours at plantations, and received corporeal punishment for any perceived wrongdoings. “Sugar” excavates this very history.

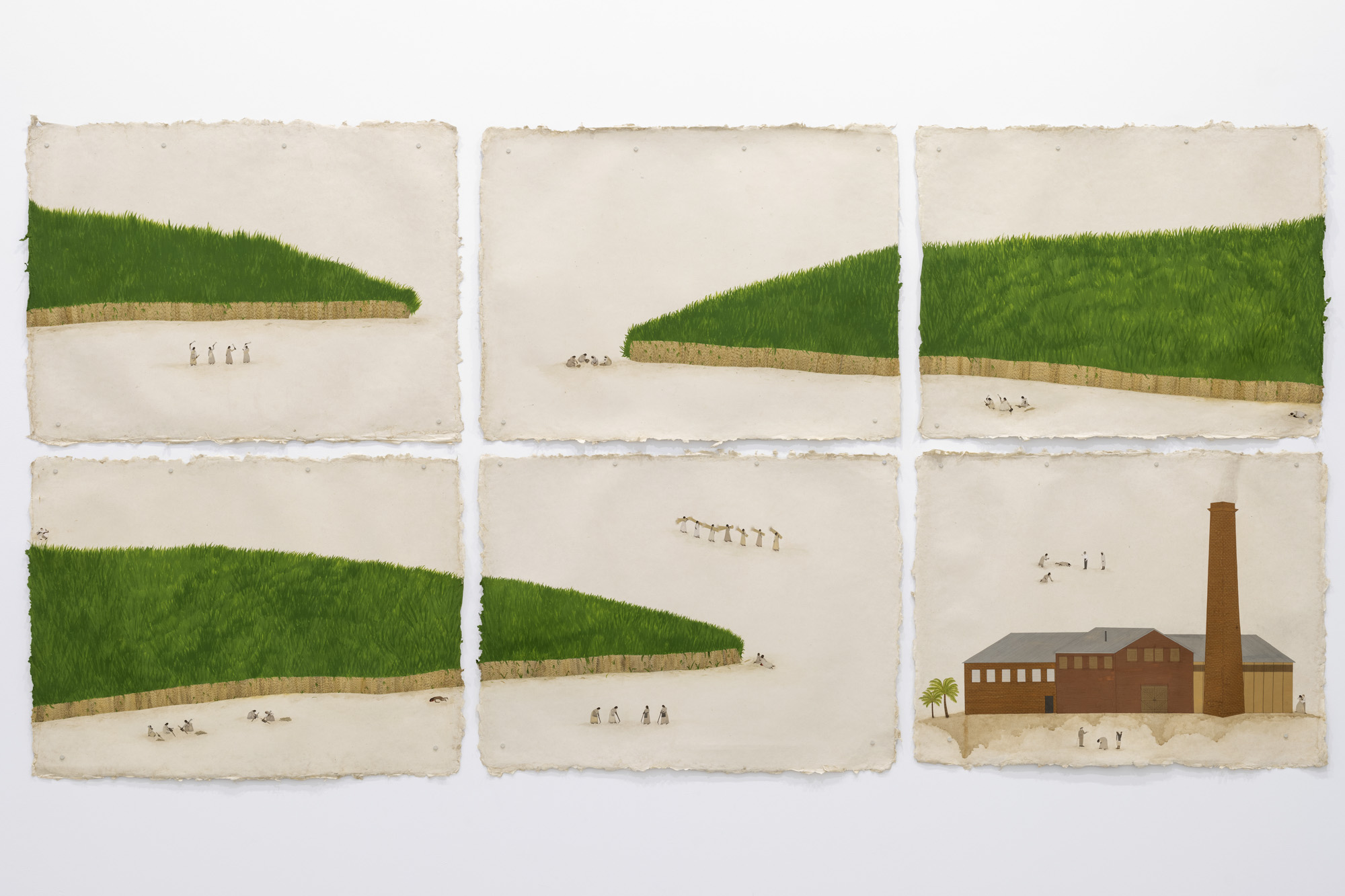

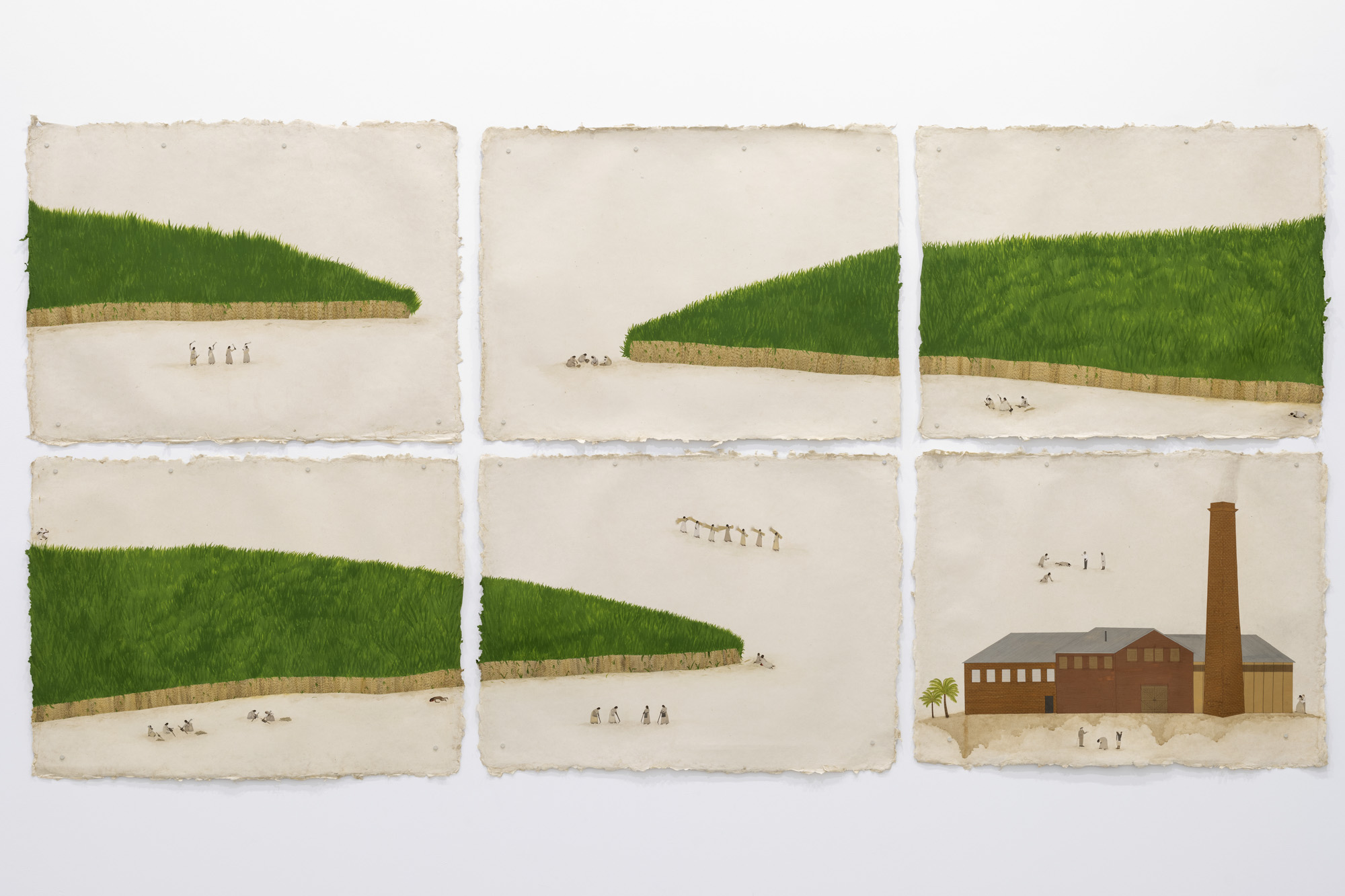

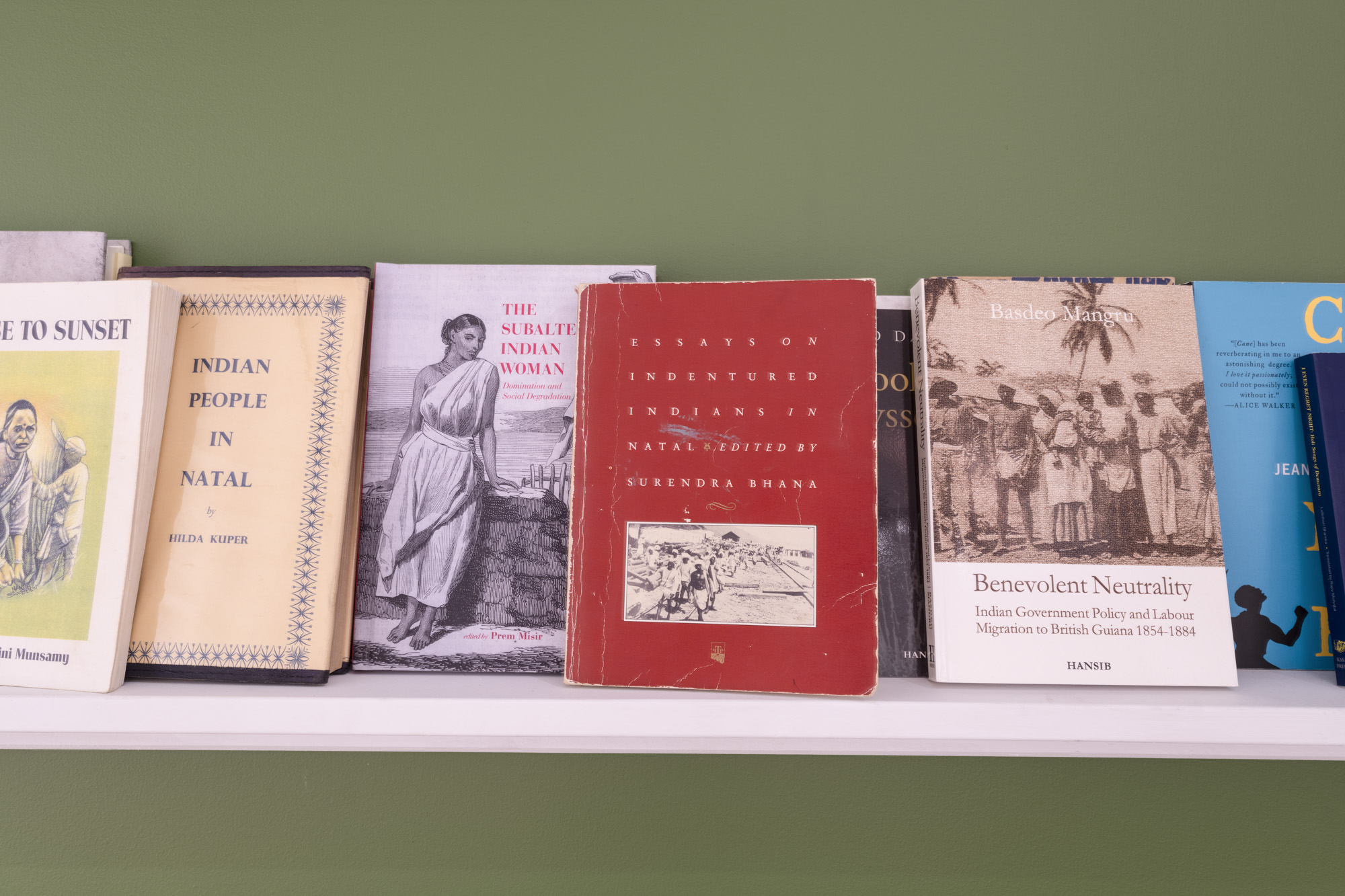

Simpson’s miniature paintings do well to explicate these histories and shine light on the all-too-invisible channels of production servicing the empires. At first glance, the paintings—which loan their style from Indian miniature painting—are gentle and delicate, but under closer inspection, the watercolors show painstaking details of labor and brutality. Take The Plantation (all 2022), for example, a nearly four-meter-long six-panel painting that was arguably the centerpiece of “Sugar.” Each panel operates as a singular storyline, opening into a dialogical narrative: one panel depicts women wielding sugarcane cutting knives, while another illustrates a group of women carrying bundles of sugarcane on their shoulders. Simpson learned the art of miniature painting from a master in India and developed her skill for a decade. While the practice is reserved primarily for religious scenes, Simpson’s labor-intensive miniature paintings build space for women whose lives unfolded on the plantations and whose caste was never honored in such a revered academic tradition.

Other depictions are laden with violence, evoking a sense of anguish for each nameless woman depicted. In The Plantation, the bottom right panel portrays a woman under attack by a White (assumably settler-colonizer) man, his arm tightly folded around her neck in a chokehold while she tries to resist. In the foreground is the sugar mill, where two men are whipping a woman into submission. Albeit smaller in scale, The River shares the same violent tone. In the top left panel, a woman’s body lies dormant, hanging from a noose tied to a tree resembling that of an acacia—a species prolific across South Africa. In the same panel one woman sinisterly floats prone in the river while another fights against the hands of a man. Each panel reveals a small window into the lives of the indentured women that were filled with sacrifice and violence but rarely acknowledged in the writings of colonial histories.

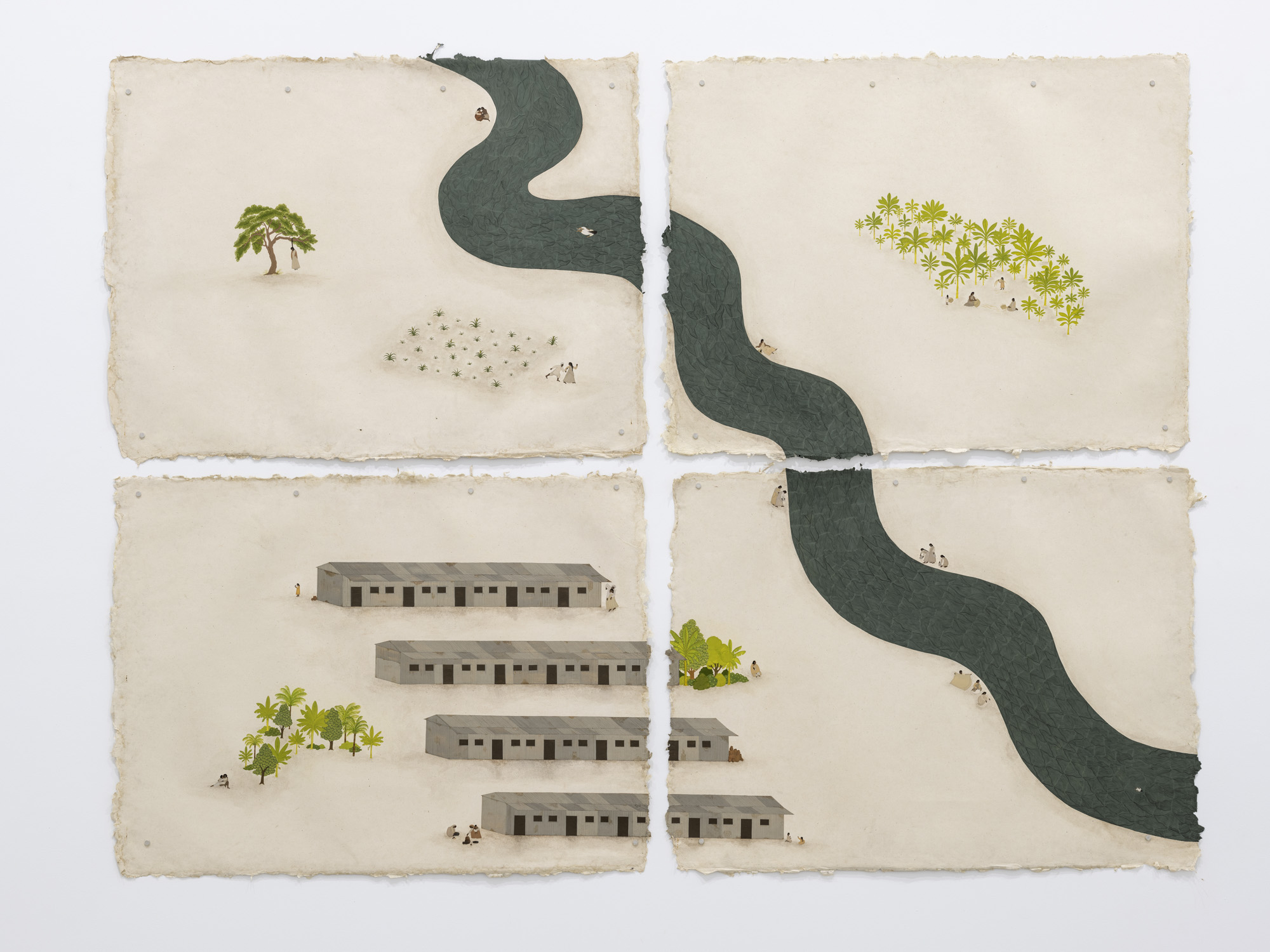

Illuminating the research behind each painting is An Archive, which recreated Simpson’s reading room in the upstair space of the gallery. Cushions lied strewn across the floor and an earthy green wall hosting an array of books completed the room with an armchair wrapped in a linen-like fabric. The texts carefully arranged on shallow shelves across the wall ranged from general historical treatises such as Indentured Labor in the Age of Imperialism, 1834–1922 by American-based historian David Northrup from 1995 to parallel histories in Kay Saunders’s Workers in Bondage: The Origins and Bases of Unfree Labour in Queensland 1824–1916 from 1982, which looks into the beginnings and beyond of the Pacific Island workforce during Australia’s convict era.

Yet key to An Archive’s success is the collection of postcards, photographic slides, photographs, and ephemera displayed across two vitrines. Collected from eBay and similar sites, these images offer a romanticized depiction of life on the plantations—worlds away from the violent content unearthed in Simpson’s miniature paintings. One image, for example, shows women and young girls smiling, dressed in white and nestled within an exotic subtropical landscape, with captions that read “young coolie, Natal.” The postcard industry, thriving at the height of Indian indentured servitude at the time, worked to capture the tension between the colonial imagination and the realities behind each image.

As colonial histories continue to unfurl and as we further develop our understandings on the violence imposed by imperialism, Simpson’s portrayals of indentured women demand space in this constantly growing dialogue.

Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s “Sugar” is on view at Milani Gallery, Brisbane, until October 29, 2022.