Shows

Ryoji Ikeda’s “π, e, ø”

“The phrase ‘data visualization’,” notes Laura Kurgan in her book Close Up at a Distance; Mapping, Technology, and Politics (2013), “is a bit redundant: data are already a visualization.” Despite the current economic and political fetishization of big data and its utility, Kurgan’s commentary speaks to the fact that data is never in and of itself pure: it is always interpreted and modified for presentation. At London’s Almine Rech Gallery, Ryoji Ikeda’s exhibition “π, e, ø” addressed how information can be visualized, and how this visualization contributes to our understanding of our own mental faculties.

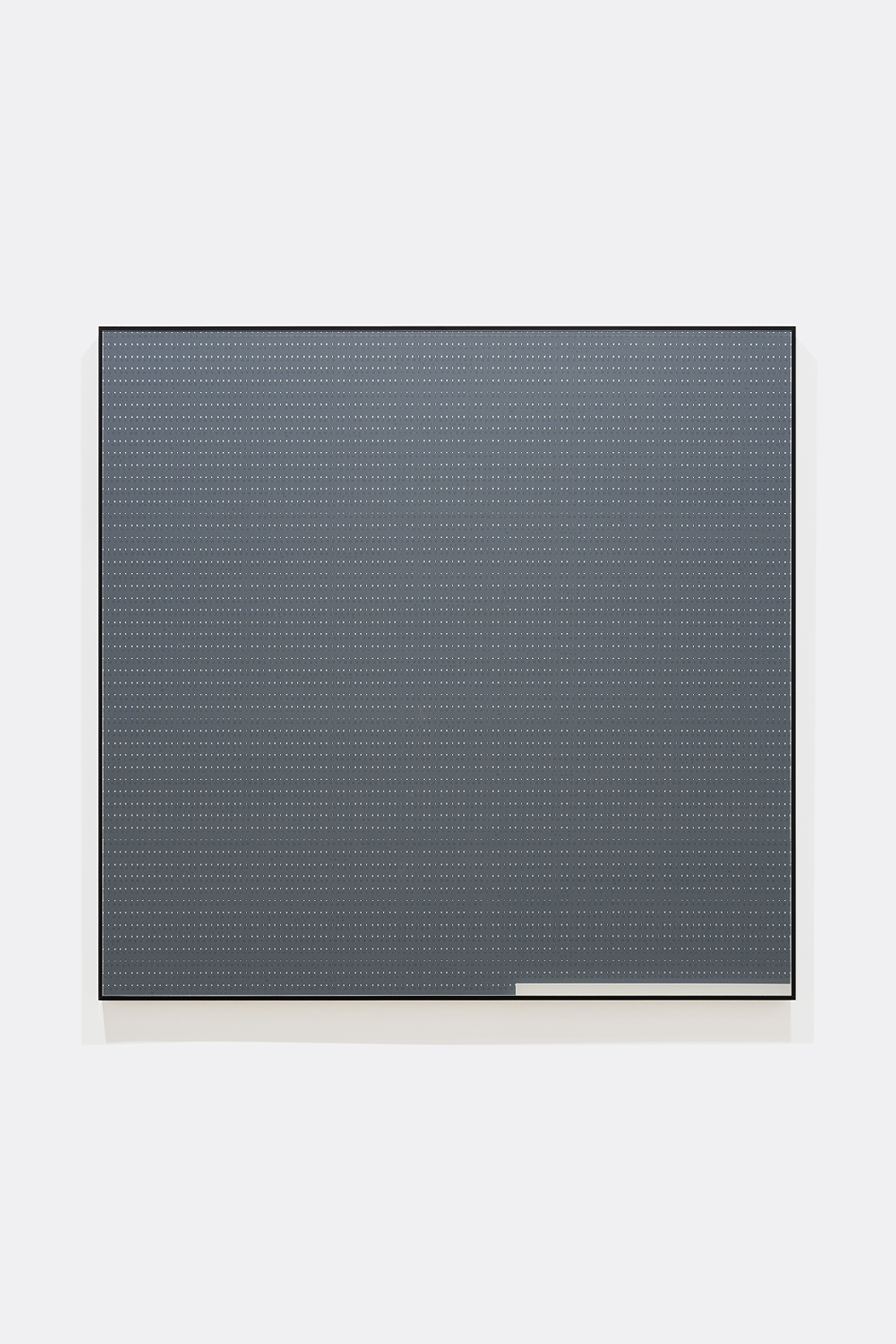

The exhibition was divided into three spaces. In the first, seven square abstract digital prints in muted tones of cream, black and textured gray lined the walls. Closer inspection revealed that these works on paper (all 2017) are digital prints of the digits that comprise the show’s eponymous mathematical constants, divided into two subgroups, transcendental and irrational. Taken in this way, the works suggest that teeming under the surface of anodyne objects are complex, but imperceptible patterns.

The second space contained the “Time and Space” series, where the materials of the moving image act as a medium to represent time. 4’33” [gray] (2014) consists of blank strips of magnetic film—the physical equivalent of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence and a nod to John Cage’s seminal work. In a similar nod to the representation of time through physical means, 0’10” (2010) frames ten strips of 16mm film to represent the ten-second countdown that traditionally precedes films. The results of these attempts are uneven, as the film strips often seem arbitrarily placed and framed, and don’t invite further inquiry, unlike the minute detail of the square pigment prints.

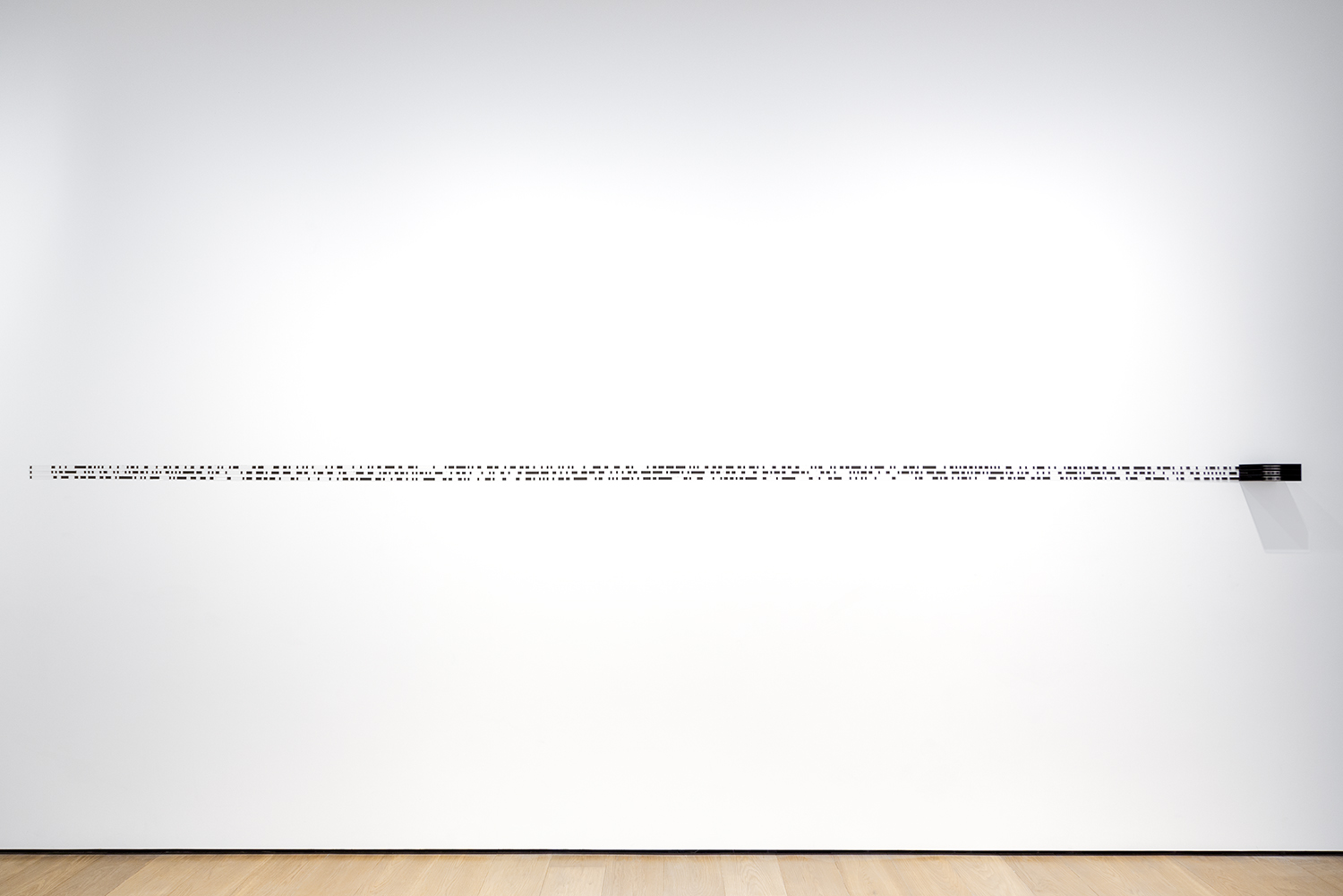

The final space was populated by nine digital displays and computers, each from the 2011 series “data.scan,” which is a continuation of Ikeda’s ongoing “Datamatics” project (2006– ). The screens display how data is employed for medical and scientific purposes, among other uses. Intermittently flickering on eight of the nine screens are specific locations of moons and stars, an unraveling DNA sequence of a chromosome, two screens of four-dimensional hypercubes, the molecular structure of a protein, digital error patterns, Morse code, and a 2D map of the universe. The ninth screen depicts the metadata of the entire “Datamatics” project. On the walls, interspersed among these screens, were Ikeda’s “Systematics” series—works that refer to the history of data’s systematic, logical expression. These works include punched paper tapes for vintage computers, Cold War-era aperture cards from the US Department of Defense’s microfilm archives that have been painted black, and fragments of piano rolls that were fed into player pianos. These materials were illuminated by lightboxes, emphasizing both their plastic materiality and the bore-holes that indicate their utility as carriers of information.

![RYOJI IKEDA, Systematics [nº1-2], 2011, punched tape for vintage computers, acrylic panels, LEDs, stainless steel, aluminum, 6 x 103 x 1.6 cm. Courtesy the artist and Almine Rech Gallery, London.](https://artasiapacific.com/rails/active_storage/blobs/proxy/eyJfcmFpbHMiOnsibWVzc2FnZSI6IkJBaHBBcXFjIiwiZXhwIjpudWxsLCJwdXIiOiJibG9iX2lkIn19--06fd84a2c3b2bb40cede39866757cd7292906592/6._systematics__n_1-2_.jpg)

![Installation view of RYOJI IKEDA's “π, e, ø” exhibition at Almine Rech Gallery, London, 2017. (Left) Systematics [nº4-1], 2011; (right) Systematics [nº4-2], 2011. Courtesy the artist and Almine Rech Gallery, London.](https://artasiapacific.com/rails/active_storage/blobs/proxy/eyJfcmFpbHMiOnsibWVzc2FnZSI6IkJBaHBBcXVjIiwiZXhwIjpudWxsLCJwdXIiOiJibG9iX2lkIn19--164ef82c6dad09642e655afcc52400268067bc92/7._systematics__n_4-1__and_systematics__n_4-2_.jpg)

Juxtaposed alongside the digital screens, these analog ephemera suggest that while data aesthetics have evolved, attempts to make data comprehensible to the casual observer remains a perennial problem. Paradoxically, this is Ikeda’s ultimate shortcoming, but also his greatest success. In order to understand the conceptual complexity of his works, one must possess either a high degree of technical knowledge, or have a wealth of explanatory material at hand. For example, in the last room, the flickering screens intermittently filled with a fuzzy, snowed-out pattern that indicated a malfunction, and there were whirring noises that suggested frenzied activity. This implied that something else was going on—something mysterious and beyond the layperson’s understanding. But as Kurgan notes in her book, this feeling must be countered by acknowledging that data “means nothing more or less than representations, delegates, or emissaries of reality.” Reality is always subject to representation, but to the extent that representations can appear convincing, technical sleights of hand make for ideal subterfuge.

Ryoji Ikeda’s “π, e, ø” is on view at Almine Rech Gallery, London, until May 20, 2017.