Shows

Roundtable Review: “Trust and Confusion”

Even before entering the doorway into “trust and confusion,” one could already detect a light, pleasing scent, its watermelon-like sweetness reminiscent of shopping malls. The fragrance was actually phenethyldioxanone overlay (E12:E16) (2020–21), an invisible aromatic installation by Sean Raspet. Surprisingly, the fruity scent was derived from petro-chemical and industrial materials. This set the tone for the entire exhibition, where constant little jolts kept viewers puzzled and perturbed.

The “fidelity and authenticity” of experience

Peculiar experiences abounded throughout the show. Upon entering the space, visitors might find themselves engaged in a heartfelt conversation with a stranger who is in fact one of the performers for Scarlet Yu and Xavier Le Roy’s Still in Hong Kong (2021). They might also discover a dark cavity underneath Celeste Burlina’s towering, stage-like structure, The Liminoid (2021), and meet with Lina Lapelytė’s Study of Slope (2021)—a pair of shoes mounted on a slanted floor. These strange engagements with the works demonstrate curator Xue Tan and Raimundas Malašauskas’s ambitious, boundary-pushing motive to turn the white cube space into “a fluctuating environment that hosts activities and sensations.”

But this is not an easy task; its pitfall is superficial interaction. The exhibition encouraged its viewers to embrace uncertainty: performers were disguised as ordinary visitors to blur the boundaries of performance; a dark, narrow room was tucked beneath a large installation like a hidden treasure trove. The curators poetically remarked: “However confused we may now feel, we trust that we will arrive at a safer place.” The irony is that the space was already safe. In the context of contemporary art institutions, it seems unnecessary to inspire “trust” in what arouses “confusion,” for the visitor will probably accept them as norms, and thus be unable to truly engage with the curatorial premise. Rather than feeling mesmerized by its “activities and sensations,” I exited “trust and confusion” with more questions about how we can “trust” the fidelity and authenticity of the experiences contemporary art offers at institutions. CASSIE LIU

“An uncanny valley”

Throughout the exhibition, the organic and inorganic engaged in an eerie masquerade. Ghostly reverberations, resembling waterphone music, were emitted from an innocuous-looking bowl of fruit in Yuko Mohri’s Decomposition, Copula (2021). In Nicholas Mangan’s Lasting Impressions (2021), realistic dental casts made of coral lay in white boxes, waiting to be discovered. Though it was chilling to find what seemed to be human remains, the realization that they weren’t human at all was even creepier. Meanwhile, the exhibition space itself mimicked natural cycles, having been divided into “day” and “night” rooms bridged by a sunset-hued passage. However, the day room was as sterile as a clinic, and brick-shaped gaps on one wall reminded viewers of its artificial construction. While some aspects of the exhibition left one hopelessly baffled (the “night room,” for example, threw no light on the interrelations between the three works it held), “trust and confusion” remained an intriguing exploration of our unspoken neuroses, placing viewers in an uncanny valley of sorts, where unknown threats lurked in plain sight. GABRIELLE TSE

“Parallel strands”

Like its title suggests, “trust and confusion” set off to cover binaries that have become “companions” in our current reality. And in many ways, it succeeded. Taken separately, or even in pairs, the works reflect the curators’ provocation to trust in the unknown. Félix González-Torres’s “Untitled” (North) (1993), for example, hints at life’s fragility, while acknowledging the possibility of revival. Installed at the entrance, the 12 strings of lightbulbs gradually burn out, and are replaced and rearranged at unplanned times throughout the exhibition’s run. The unintentional allusion to “burnout,” the modern workplace affliction, is hard to miss.

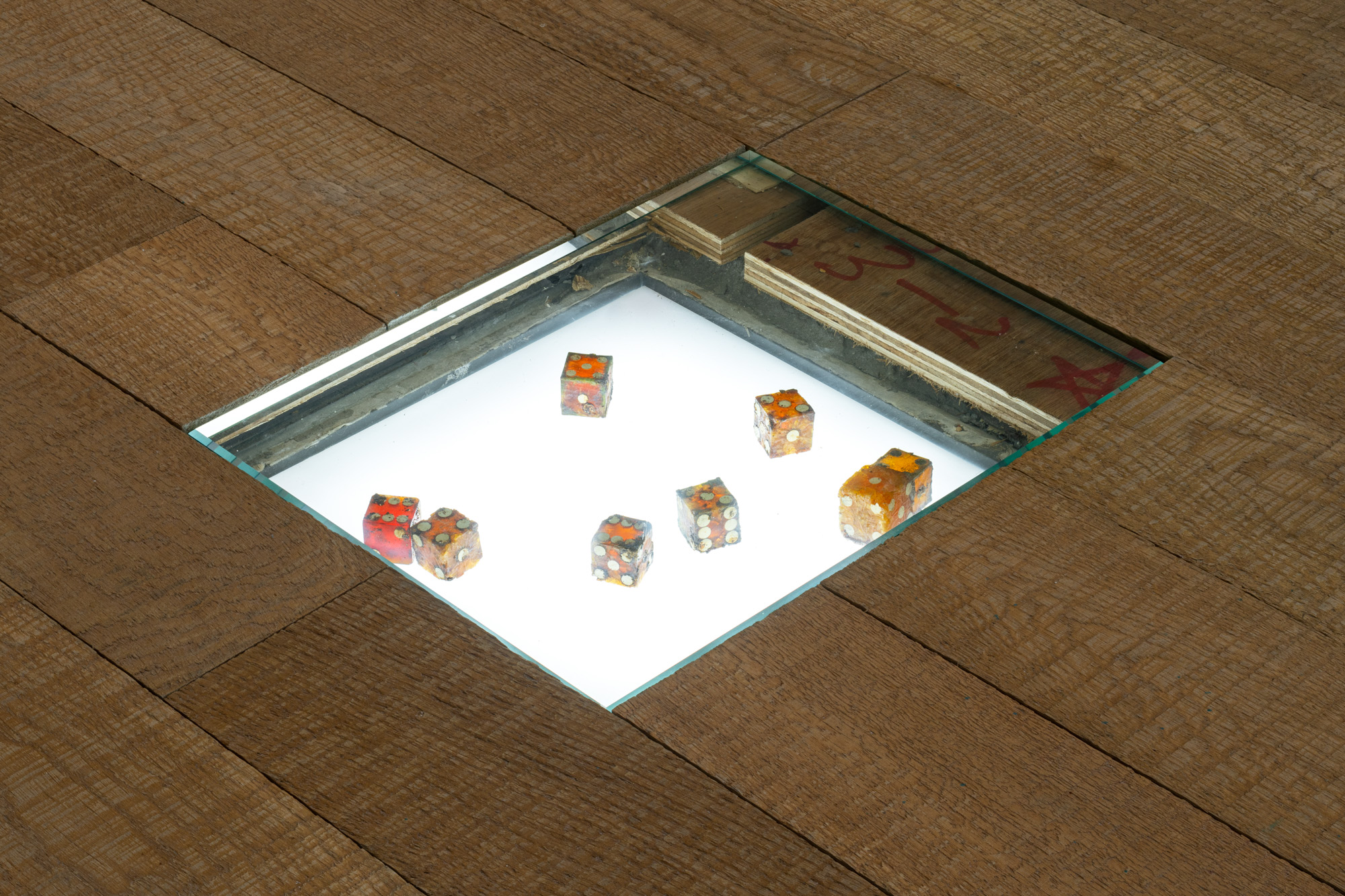

Other works, such as Decaying Dice (date unknown), embody the theme of chance. Two sets of cellulose nitrate dice from late American magician Ricky Jay’s collection lie in separate lightboxes implanted on the gallery floors. Their decomposing, translucent yellow bodies mockingly glow at viewers’ feet, as if reminding them that their lives are dictated by forces larger than them.

Yet, like parallel strands, these themes never quite reach one another. Whether it was the clashing reverberations of Yuko Mohri’s fruit sonic sculpture Decomposition, Copula (2021) with Lina Lapelytė’s tone-deaf choral songs in Study of Slope (2021), or the awkward juxtaposition of Claudia Fernández’s colorful paper lanterns in Constellation (2015) that accompanied the rolled foam mattresses of Tarek Atoui’s Whisperers, Module #5 (2021), there seemed to be too many disconnected elements. Even with small pockets of security, the exhibition left me feeling more confused than trusting. JUDY CHIU

“Destabilizing”

“Trust and confusion” felt a little bit like purgatory, a liminal space filled with works caught in their own states of in-between. Inside, displays spilled over and rubbed unsettlingly against each other: a trail of lightbulbs fell from the sky as a siren ripped through the sound of popping balloons. Somewhere, a feather duster thumped twice.

Rising in the far corner, Celeste Burlina’s The Liminoid (2021) gave pause, the stainless-steel structure being neither bleachers nor a skatepark nor a stage despite evoking all three. Tarek Atoui’s Whisperers (2021) distorted familiar songs, sending them through assemblages of copper, cloth, wood, and polyurethane in hopes of revelation. The viewer’s experience was destabilizing, and it seemed as though the curators hoped this impact would be cushioned by gusts of chance intimacy. Yet the works never really landed, and not even the transient sweetness of the hour-long conversation with the actor in Scarlet Yu and Xavier LeRoy’s piece of invisible theatre, Still in Hong Kong (2012), could remedy this lingering feeling of not quite, the connection a touch too accidental even for a work that intended to rest on chance.

Ultimately, the balance between “trust and confusion” seemed off-kilter, and it was difficult to trust that we would be delivered through confusion to epiphany. Though considering each piece individually allowed the echoes of each theme to emerge, the exhibition didn’t quite manage to thread them together as a whole. Like the two spoons in Yuko Mohri’s Copula (2021), they would occasionally touch long enough to turn on the light—but it would not be sustained. SUINING SIM

“Give yourself over to it”

The title says it all. But what it doesn’t spell out is the relationship between these two experiential states—and the precarious feeling of rocking from anxiety to comfort, skepticism to pleasure, trepidation to euphoria. But with forms of live art that are not bounded by traditional frames such as the stage or the choreographed performance, “trust and confusion” gestures toward the degree to which you must summon the former to overcome the latter in this ever-unfolding exhibition. For instance, someone might approach you and ask to breathe with them (Alice Chauchat, Unison, as a Matter of Fact (trust and confusion), 2021); if you choose to join them, the experience will be yours. Someone else might strike up a casual conversation and then over-share their life story (Scarlet Yu and Xavier Le Roy, Still in Hong Kong, 2021), which might lead you to reflect on your own. You will likely be offered a balloon to pop, yielding a rolled-up piece of paper with a cryptic message that stays with you for the rest of the day (Serene Hui, Rehearsal for Disaster – The Explosion, 2021). Other sounds and movements might interrupt your experience of the stationary works in the gallery. Someone invited me to listen to a story and then recited the first half of The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde while we sat outside in the courtyard (Mette Edvardsen, Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine, 2010– ). In a similar vein, Pan Daijing’s performance in a totally darkened gallery space on the night of a full moon tapped into the post-pandemic novelty of just being physically, and experientially, together. If you can give yourself over to it—whether it is sound, a dance, or words—live art will come alive in you. HG MASTERS

“A gamble”

Ricky Jay’s eerie Decaying Dice (date unknown) encased in Tai Kwun’s wooden floor reminded me of French poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous and ambiguous poem “A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance.” The idea that each result is just one of many and doesn’t change the random nature of the dice gave me some clarity about the show. The curators of the evolving, seven-month-long exhibition encourage the audience to check in multiple times and detect the latest changes. Every visit, then, is like a gamble on what one may encounter. The first time I went, a dancer was demonstrating a set of robotic movements based on the evacuation protocol of the museum for Nile Koetting’s Remain Calm (Mobile +) (2021), while other performers approached visitors to tell them their personal stories of being stuck in the city for Scarlet Yu and Xavier Le Roy’s Still in Hong Kong (2021). During my second visit, I was asked to hold a balloon while walking through the exhibition, as part of Serene Hui’s Rehearsal for Disaster – The Explosion (2021); I was nervous to pop the balloon, which I had to do to find the hidden note inside. As for the third time, I jumped at the sudden movement of the broom in Yuko Mohri’s kinetic structure Copula (2021), not remembering if I’d seen it previously. It is difficult to tell how much effort the general public would be willing to spend on revisiting the show and decoding each interactive work. Nonetheless, the viewing experience is meant to be incomplete and fragmented, as each encounter is just one part of many possible combinations. PAMELA WONG

HG Masters is ArtAsiaPacific's deputy editor; Pamela Wong is assistant editor; Cassie Liu was editorial assistant; and Gabrielle Tse, Judy Chiu, and Suining Sim were editorial interns.