Shows

Reexamining Knowledge Systems in Shubigi Rao’s “Eating One’s Tail”

“Eating One’s Tail”

Shubigi Rao

Rossi & Rossi, Hong Kong

Mar 18–May 13

Many myths tell of the Ouroboros, a primordial serpent which devours its own tail in an endless cycle of self-cannibalization and regeneration. From this lore emerged “Eating One’s Tail,” the first survey exhibition of Indian-born Singaporean artist Shubigi Rao in Hong Kong. Through examining knowledge systems informed by violence or displacement, her drawings, films, and photographic installations embody creative and destructive forces’ equal importance to life.

An arresting reading-room setup greeted visitors near the entrance. Four chairs arranged around a rectangular writing desk sat in the center of the main gallery, surrounded by walls affixed with white open shelving lined with potted plants, rock tchotchkes, and Rao’s various publications. Sat comfortably on the bookshelves, volumes of Pulp (2016– ) offered visitors an anthology of real interviews and factual writings on the artist’s decade-long research into histories of book destruction, censorship, and repression, alongside mitigative and conservation efforts. The most direct of Rao’s indirect critiques of human hubris, Pulp then serves as the most important connecting thread between her re-imagined worlds and reality. It demonstrates the power of the book, through which violent histories may yet birth restorative change.

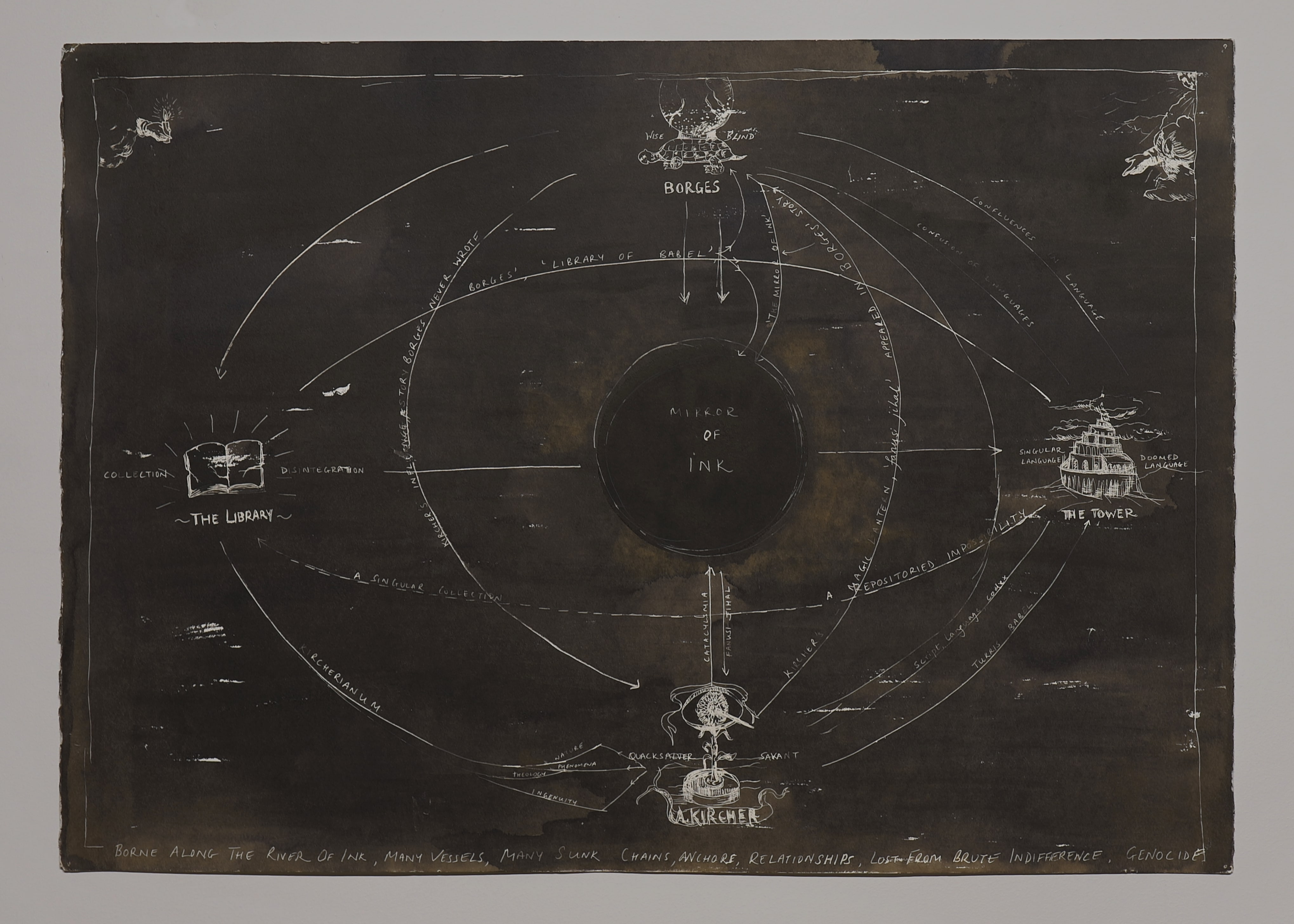

On a wall behind the writing desk hung The Mirror of Ink, Or, a Guide to the Four Pillars (2016), a striking set of framed ink illustrations arranged in a T-shape. A cartographic diagram in the middle delineates the relationships between archetypes of knowledge positioned at cardinal points. The illustration makes sense at first glance but becomes mystifying upon closer inspection. Institutions connected in Rao’s picture either possess but tangential connections—such as “The Tower of Babel” and “[Athanasius] Kircher,” 17th-century Jesuit scholar and founder of Egyptology—or exist as universally fluid concepts, like the mytheme of the World Turtle appearing across ancient Indian, Chinese, and Native American cultures. White arrows and ambiguous prose, more ornamental than symbolic, link these icons in a contentious web. Yet, exposing these conceptual loopholes is precisely Rao’s intention. Looking at her drawings, the viewer is confronted with the ironies of knowledge production and consumption: if everything we presently know is based on assumptions, then who can attest the validity of time-tested constructs—products of a similarly flawed ecosystem of ideas?

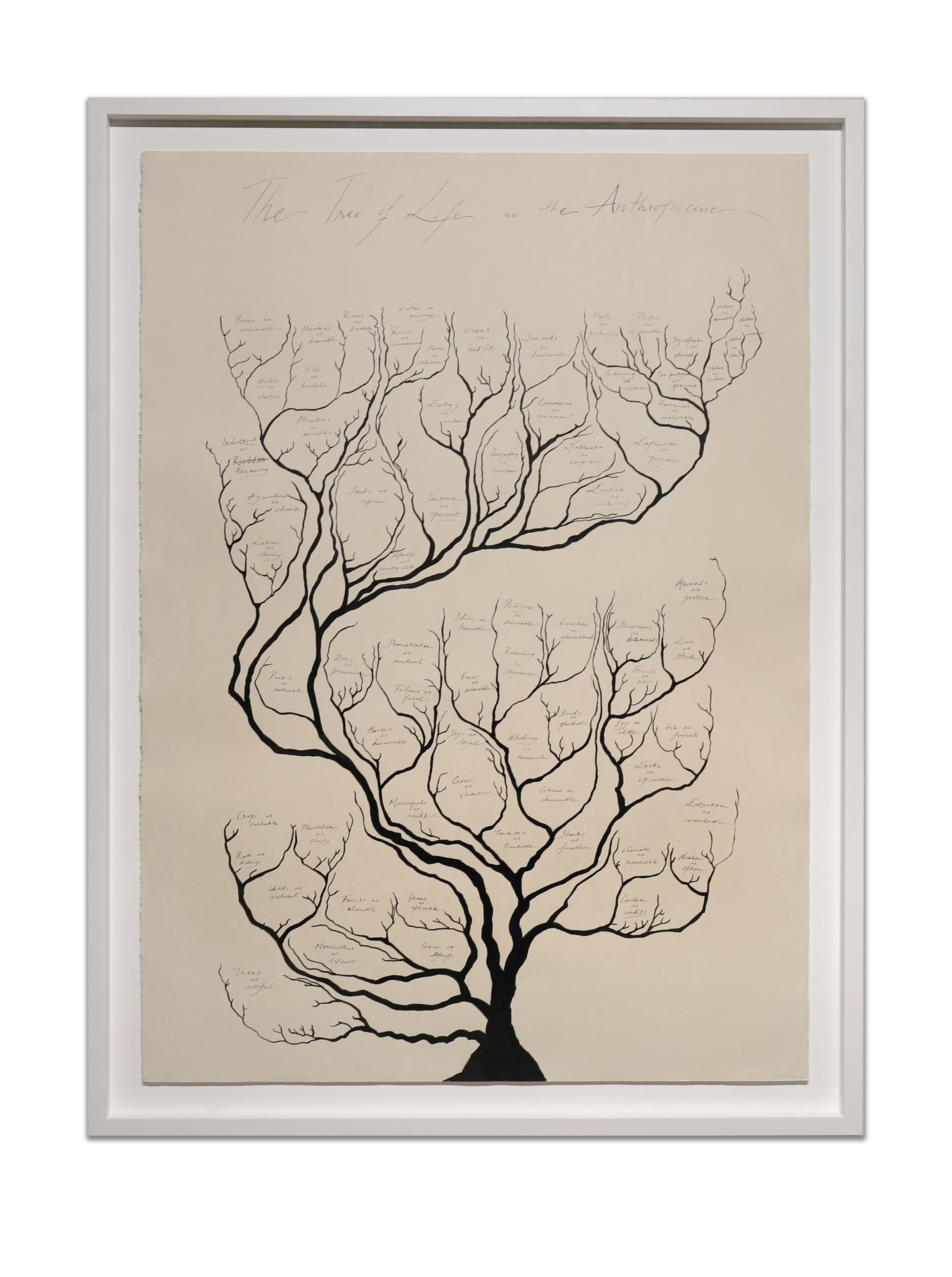

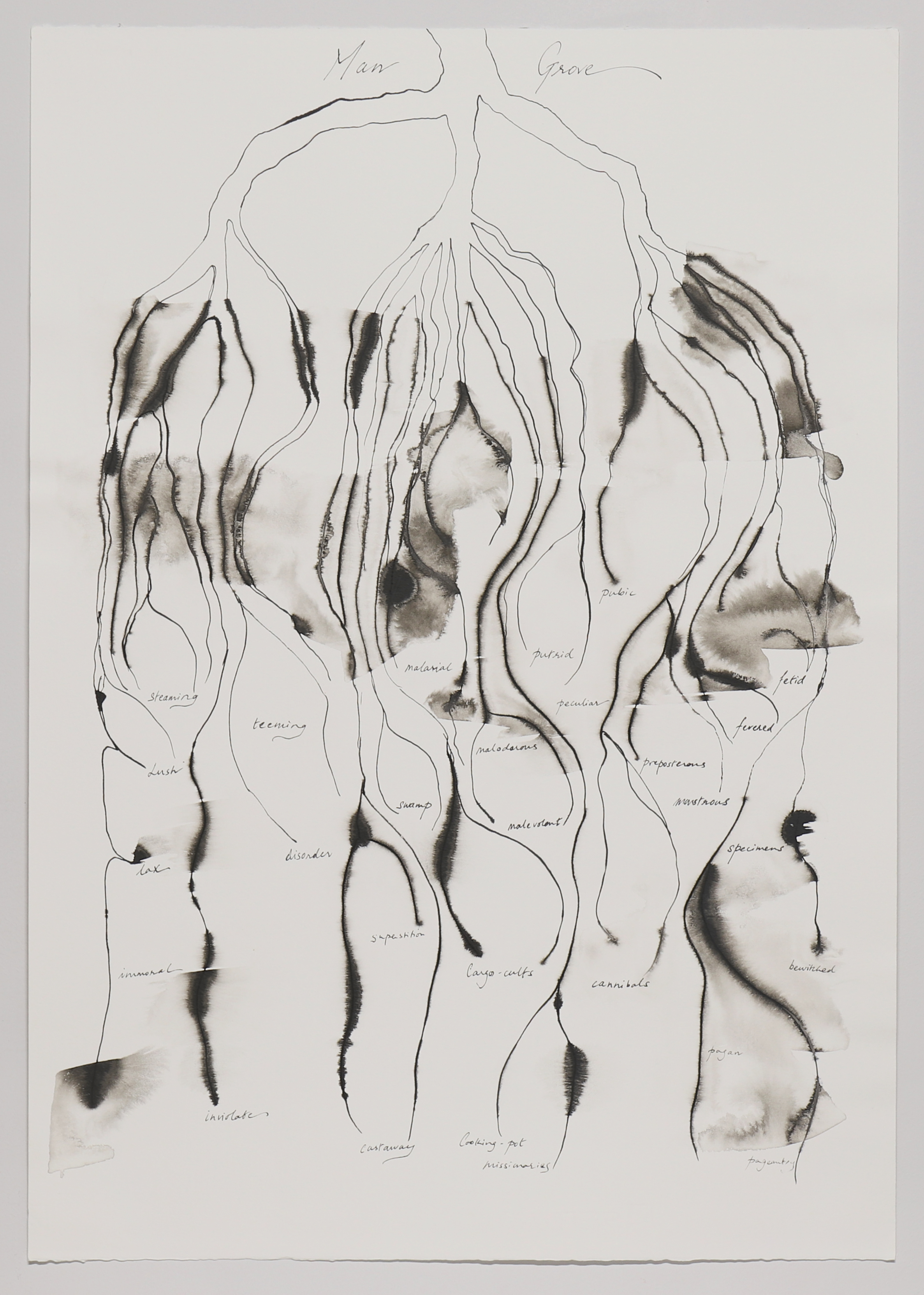

Knowledge structures and flows are similarly visualized through tree diagrams in nearby works, Tree of Life in the Anthropocene (2016) and The Man Grove (2019). Juxtapositions of creation besides destruction manifest between the upward extending branches in Tree of Life and ink-smudged roots of The Man Grove. While destructive impulses are immediately apparent in the latter, closer reading is required to pick out the contradictions within the former. Rao’s Tree of Life is nourished by capitalistic remarks such as “Nature as currency” and “Breeding as commerce.” Its blackened branches and wizened trunk emphasize the rot embedded in our societies. More than functioning as a collective exposé, though, this hodgepodge of hypercritical quips mimics the flawed process of narrative formation; that being humans’ tendency to gather and morph disparate data into plausible stories aligned with our intentions.

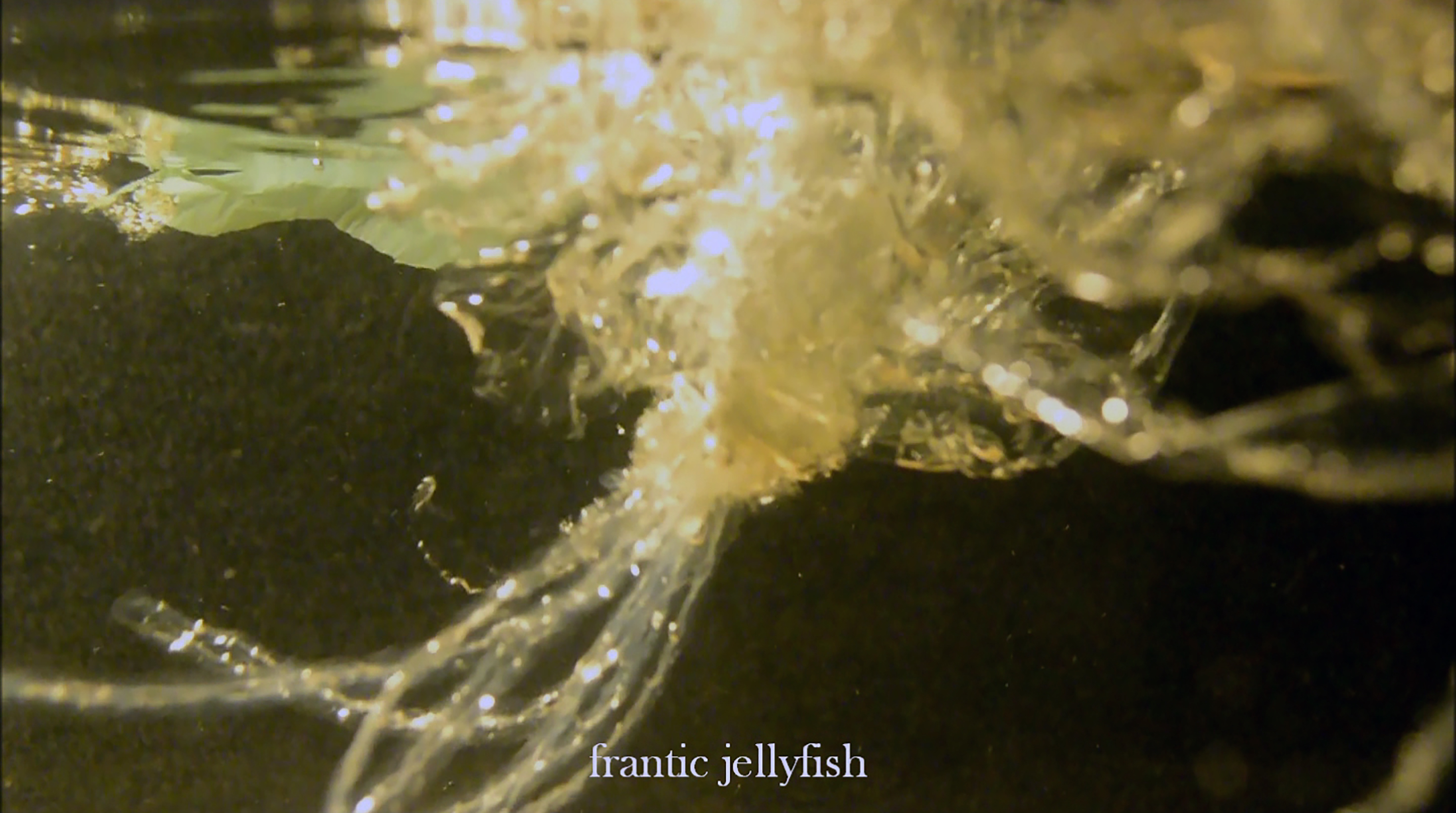

Rao herself acknowledged that books “are really a cover for talking about violence.” The myriad references and allegories she has developed over the years are by-product of a top-down sociopolitical climate. More significantly, the glaring self-reflexiveness of most of her works might be Rao’s pointed response to the problematic histories that exclude some others in favor of a few. In Stabbing at Immortality: Building a Better Jellyfish (2013), Rao’s male persona, scientist-theorist S. Raoul’s research on the immortal jellyfish mocks the futility of humanity’s quest for immortality while highlighting misogyny prevalent in academic fields. The single-channel video installation is supplemented by adjacent wall-text and publications (available for perusal at the entrance) detailing the fictional pourquoi story of the immortal jellyfish by the similarly fabricated character. In an intentional complication of authorship and achievement, Rao pens numerous scientific papers (albeit falsified) under Raoul’s name while deferring to him as her “superior”—she claims to be his assistant and protégée.

As layered and cryptic as Rao’s fictions were, an exhibition comprising entirely of her make-believe worlds would have seemed frivolous. The show better contextualized her larger polymathic practice, with works on display guiding the visitors from the macro to the micro, bringing into perspective the vastness of the cosmos. Standing in Rao’s universe, I was reminded that for all our grandiloquence, humans are but specks in a big, big world.

Tong Tung Yeng is an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.