Ideas

Recap of New Rituals: Aïsha Devi feat. Asian Dope Boys + Pan Daijing

If a lesson could be extracted from “New Rituals”—a pair of music, dance and multimedia performances at London’s Barbican Centre that took place on October 7—it’s that grotesque is a relative term. The first, Aetherave (2018), involved live music from electronic artist Aïsha Devi, with choreography by members of the performance collective Asian Dope Boys (ADB), one of whom, the Chinese artist Tianzhuo Chen, also provided visuals.

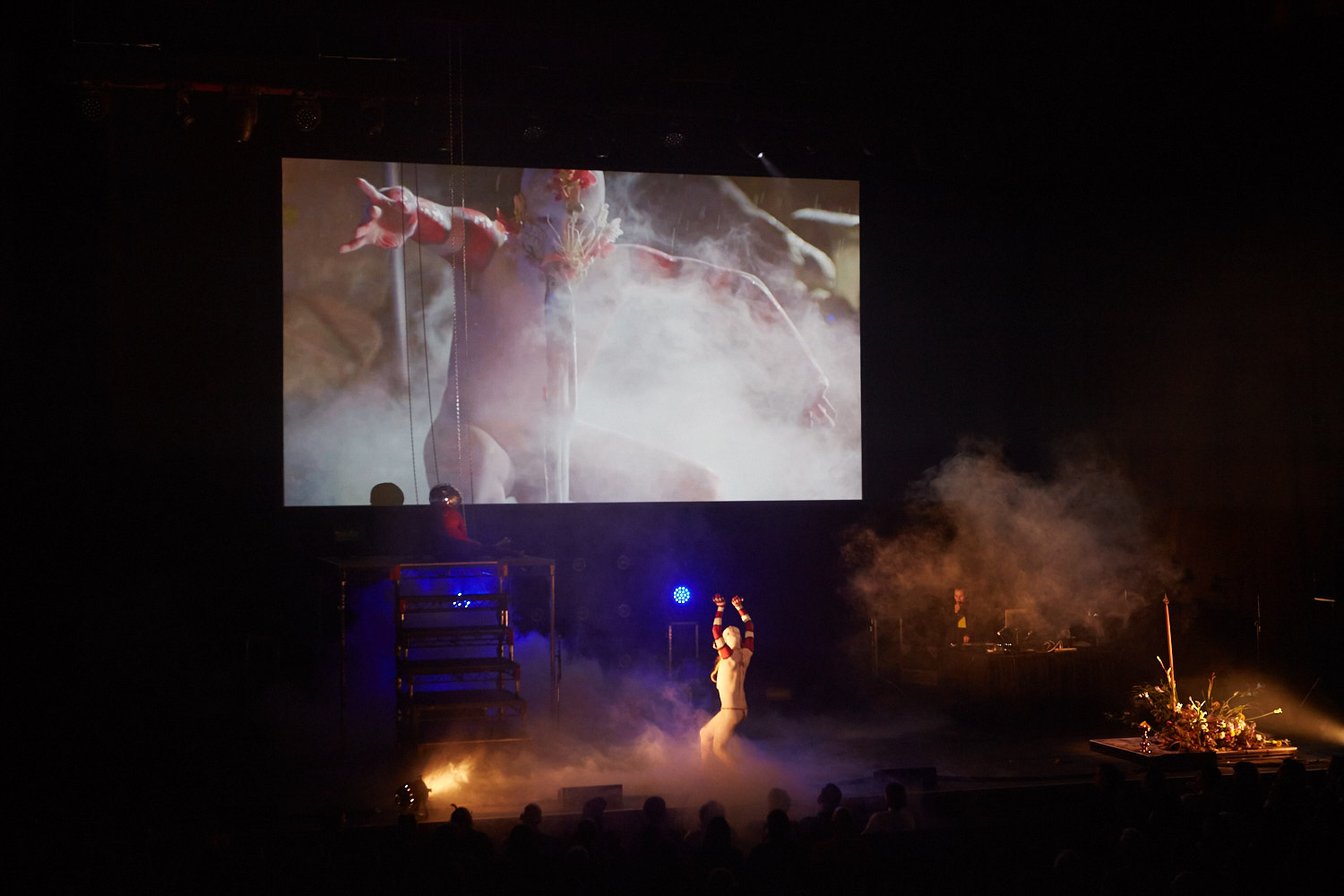

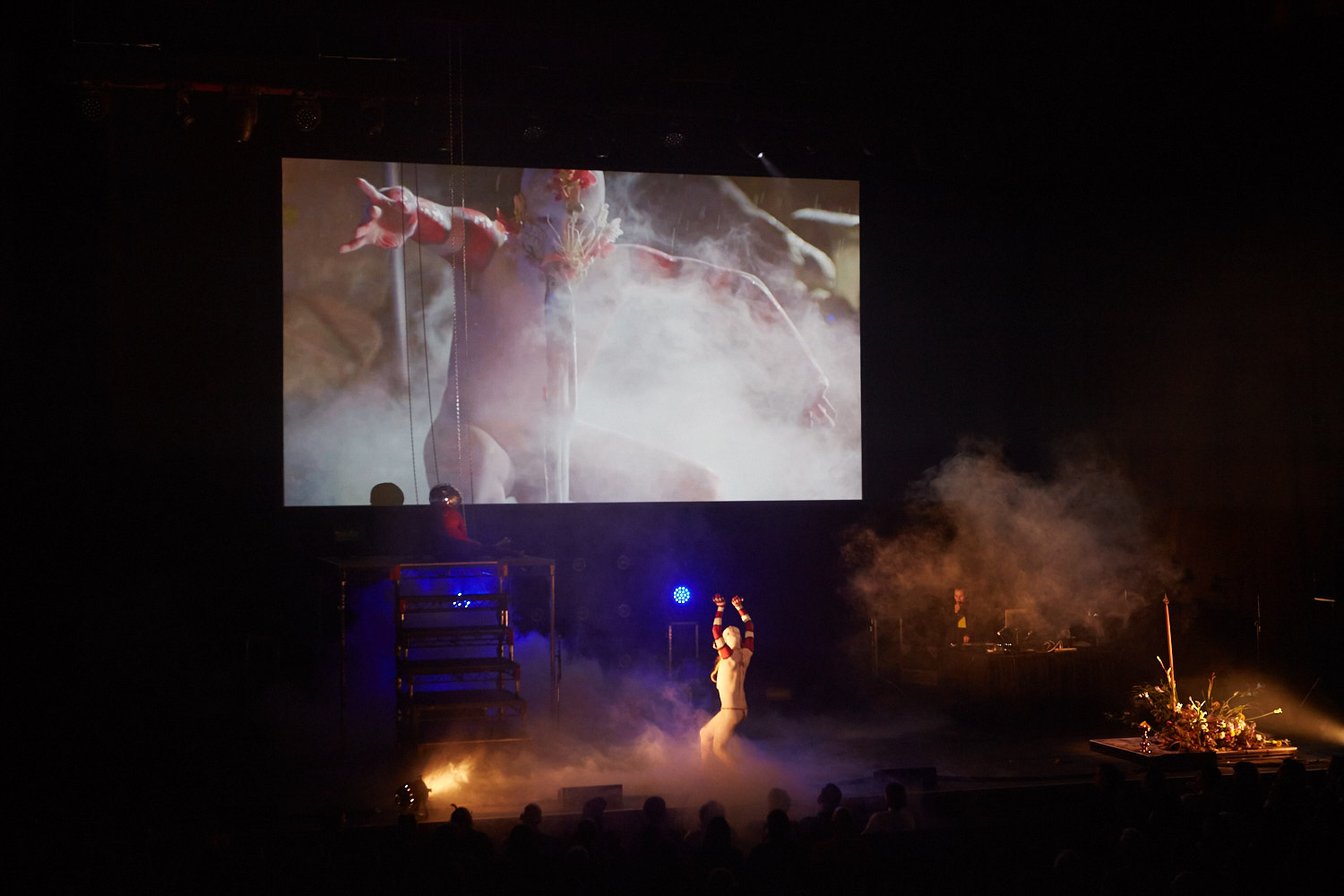

The assault of a performance began with intense beats and bass from Devi, while dancer Yi Li stood stage-right in a small, garden-like piece of mise-en-scène, naked and covered in white makeup but for his arms, which looked, and moved, like two venomous red and black snakes. A second dancer, Han Yu, knelt atop a scaffold center-stage, covered in red body paint and wearing a bulbous, silver headpiece. Screens either side of the stage displayed gray, industrial-seeming waters flanked by logging stations in which Yi Li and Han Yu—their appearances strongly reminiscent of Buddhist and Hindu mythological figures—lay in positions often implying ritualized power dynamics, such as one figure straddling or standing over another.

As Devi’s relentless live performance from the back of the stage drove the two dancers to explore their surroundings, possible influences from a range of electronic music pioneers surfaced: the rising, delay-laden arpeggios of The Knife, the sharp atmospherics of Arca, and even, at times, pitched-up vocals and erratic synths recalling the better tracks produced under London-based label and art collective PC Music all added to the performance’s hypnotic effect.

At one point, Han Yu rose to his feet, and a spotlight revealed his bulbous mask to be a disco-ball with glowing green eyes, reflecting focused beams out into the auditorium. His dancing, overtly sexual and yet curiously genderless in its movements, was initially provocative, as were the animalistic, sexually submissive dynamics he assumed while interacting with others on stage. In time, the shock faded to passive acceptance, and then to an awareness of the beauty in his body, his movements, his interactions. When another dancer, Elaine Edou, entered from the left of the stage, covered in black body paint and with a trio of hanging red braids from her head, the deliberate jerkiness of her movements, like those of someone either mad or in body-contorting pain, was genuinely frightening. And yet, in time, the grotesqueness she conveyed ceded to a kind of beauty too. Towards the end of the performance, at what could be seen as the apex of this grand ritual, she and Yi Li—respectively black and white from head to toe—descended into the aisles from either side of the stage. She moved constantly and with incredible control, while he would take a few steps and fall before getting up and continuing. As they met in the center of the audience they engaged, grinding each other like two enormous and opposing forces, both spiritual and carnal, before returning to the stage, leaving behind them a sense that something, somehow, had been cleansed.

It’s difficult to say how such a piece, with visuals of levitating sex doll-like figures, conscious aesthetic bastardizations of symbolism from a variety of faiths, and a pounding score, could leave viewers with a sense of peace, but it did—perhaps in pushing the profane in the language of the sacred, it exhorted the audience to embrace the darker parts of what it is to be human.

The second performance, Pan Daijing’s Fist Piece (2017), was a slower-burning, more measured affair. Video projections by Ekaterina Reinbold evoked physical sensation and brought an awareness to the body through the touching and manipulation of flesh, accompanied a more varied, atonal and atmospheric soundtrack than Devi’s, more organic in its arrangements and use of recognizably non-synthetic instrumentation. A dance performance featuring Gregori Homa, marked by sharp movements and angular arm gestures, also bore a less elevated quality than the previous show. Both, in any case, powerfully conveyed the sense that something deeply human—in spiritual and carnal terms—can be extracted from the grotesque and chaotic.

Ned Carter Miles is the London desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.