Shows

Progressions of the Rainbow in “Ay-O: Hong Hong Hong”

Dec 15, 2023–May 5, 2024

Ay-O: Hong Hong Hong

M+

Hong Kong

In 1966, the 35-year-old New York-based artist known as Ay-O installed Rainbow Tactile Room (Rainbow Environment No. 3) (1966) in the Japan Pavilion at the 33rd Venice Biennale. The artwork comprised three-meter-tall curving walls painted in bands of color and was adorned with 65 small wooden boxes into which visitors could poke their fingers, feeling different material textures, cool water, or triggering sounds like a bell or the radio. Though he was one of four artists selected that year to represent Japan, his presentation stood out, making him a popular sensation at the Biennale and earning him the lifelong reputation as the “rainbow artist.” In a history of the Venice Biennale from 1895 to 1968 written shortly thereafter, the critic and curator Lawrence Alloway described Ay-O’s presentation as “one of the first multi-sense artworks to be seen in the Biennale and certainly a sign of many environmental displays to come.”

M+’s exhibition “Ay-O: Hong Hong Hong” brought together several strands of influences that led him to become the internationally celebrated “rainbow artist.” The first of these was his background in oil painting. In the 1950s, while the young Takao Iijima was a student in the art department of Tokyo University of Education, he adopted the moniker Ay-O (靉嘔), an oddly prescient name whose kanji characters can mean “cloud” and “vomit” but also, in part, echoes the Japanese title of Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea. In his paintings from the 1950s in “Hong Hong Hong,” we can find glimpses of the devastation of the past, and the early dawning of a new era and its struggles. Sunflower and Jet Plane (1955) shows the black silhouette of a jet plane roaring overhead. Next to it, in another canvas, small jets leave white trails in the sky behind a giant orange-petal sunflower—its white core reminiscent of an atomic flash—with the painting’s distorted shape creating a sense of unease.

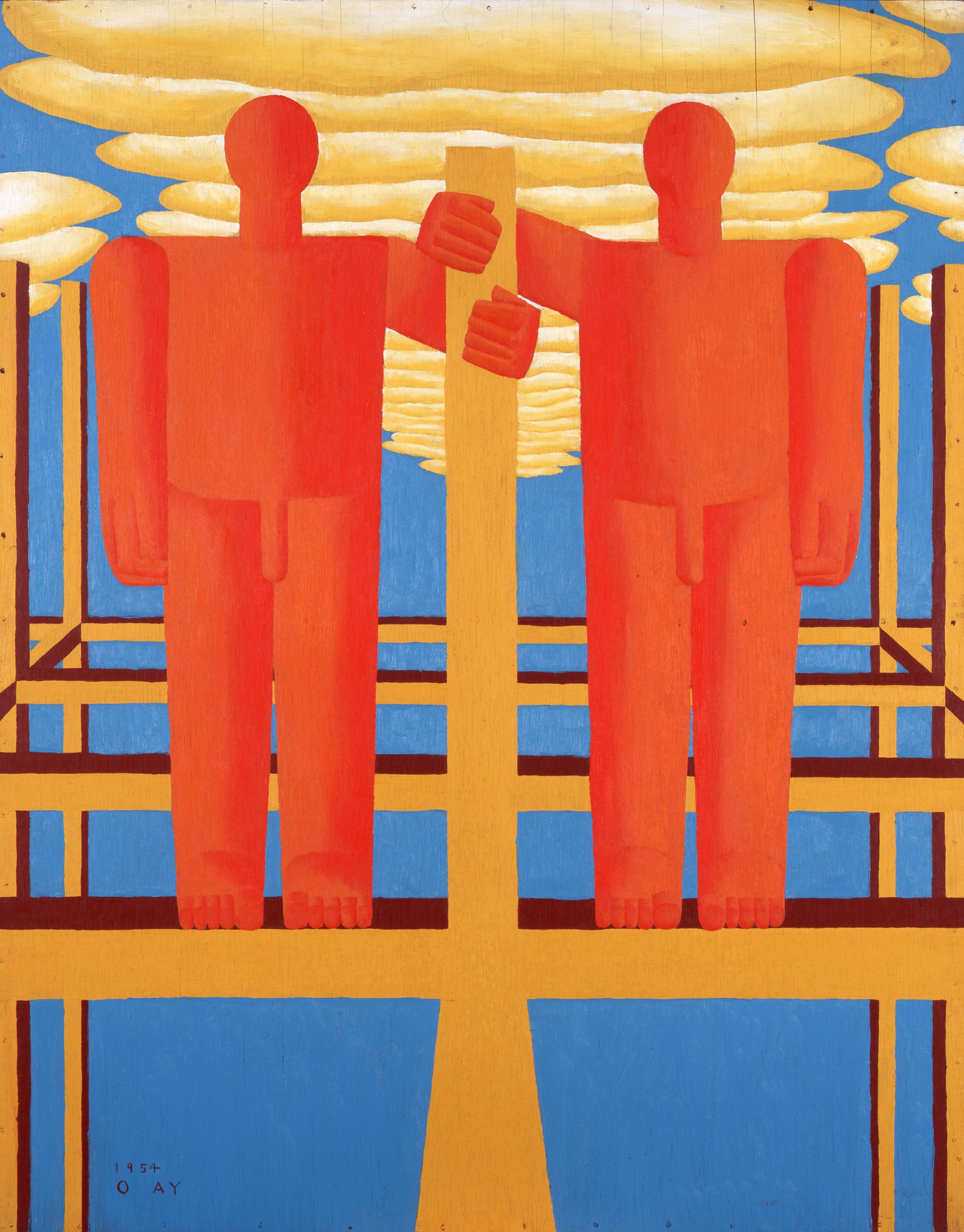

As the country rebuilt itself after the Second World War, Ay-O represented human figures as faceless bodies, standing on yellow grids of steel construction beams in the sky, as seen in To Love (1954) and A Scene with Three Clouds (1954), or through a pair of clasped hands with similar yellow structures and blue sky behind them, Untitled (1955). In the vertical canvas Steel Frame (1956), tubular figures are interspersed between orange and yellow girders. These works were created during Ay-O’s association with the Demokrato (“Democratic”) Artists Association and the brief formation of his own collective known as Jitsuzonsha (“The Existentialists”). In “Hong Hong Hong,” they represented his early forays into creating leftist, yet still individually distinctive, artworks about the solidarity between workers amid the modern cities rising from the ruins of postwar Japan.

Then, in 1958, Ay-O moved to New York—like On Kawara, Yayoi Kusama, Yoko Ono, and many other artists and musicians of the Japanese avant-garde scenes of the time. Three years later, Ono introduced him to George Maciunas and her circle of friends. Many were former students of John Cage and they came to be known as Fluxus through their publications and manifesto. Their individual approaches to art-making were process-oriented, performative, and “anti-art,” in the sense of rejecting the grand abstract paintings and sculptures that had become high-modernist orthodoxy in the 1950s. Displayed in a vitrine at the M+ exhibition, Mieko Shiomi’s handheld geometric sculpture Endless Box (1963/64/87) and a briefcase full of 15 of Ay-O’s cubes from the Finger Box Kit (1966) are examples of the many “multiples”—small sculptural objects, posters, zines, and other reproducible artistic tchotchkes—that the Fluxus group produced and packaged in boxes or containers. On an adjacent wall were films from Maciunas’s Fluxfilm Anthology, including several iconic works by Yoko Ono, such as her Film No. 4 (BOTTOMS) (1966), six minutes of a close-up shot of a human butt, and Nam June Paik’s reel of unexposed film, Zen for Film (1962–64), giving hints at the humorous and esoteric productions of this group.

How and why did Ay-O begin to use the rainbow? “Hong Hong Hong” does not provide a direct answer but offers hints, first in two small works from 1958, both untitled. One is a piece of paper covered in a field of tiny watercolor dots, and the other an oil-on-canvas of 12 colored circles on a washy blue ground. These represented the period after Ay-O moved to New York when he initially began to make delicate pointillist-like paintings and then attempted larger New York School-style “action paintings” and “combines” incorporating found materials. During this transitional period of 1958 to 1963, he moved away from abstraction, which he found too elitist, and settled on his own idea of “concrete art.” Inspired by an encounter with John Cage, Ay-O began using materials from daily life and decided he was interested in the five human senses. He made a series of small boxes that you could insert your fingers into then gradually larger ones for an arm and eventually a whole body. His interest in tactility led him to make a perfume project for scent, a dinner event for taste, and a concert performance for sound. Finally, he reflected on the nature of sight itself. He wrote later, for the catalogue of “Over the Rainbow: Ay-O Retrospective 1950–2006” at the Fukui Fine Arts Museum, that he conceived the very first rainbow in his empty studio after shipping his works off for a show in September 1962. He unrolled bolts of canvas and hung them around the empty space and began painting bands of color, a process that he said, “made me feel like I had the entire universe in my hands.” Later, when he had finished, “What made me the happiest when I completed this environment filled with rainbows was that the work became a wall, not a painting like in my past. I no longer had to paint a picture.”

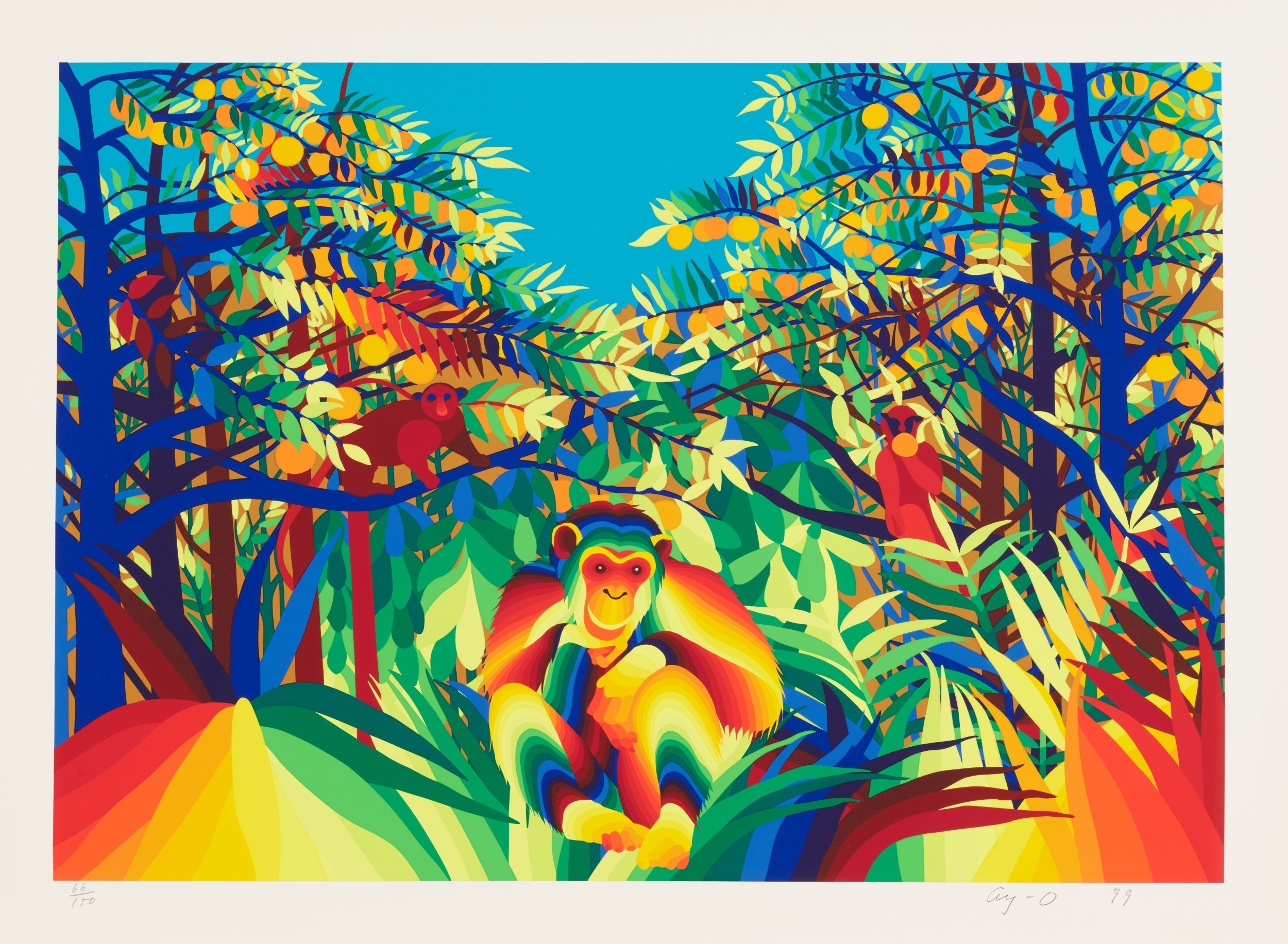

As experienced in “Hong Hong Hong,” once he adopted the rainbow, he used it to cover all manner of found objects and surfaces ranging from a human skeleton, Inner Rainbow Skeleton (1990), to small objects such as a pair of drinking glasses, to many variations on canvas. At M+, the pair of identically sized paintings, Rainbow Rain A (1976) and Rain (1977), show bands of thin paint bleeding into each other, whereas in his most iconic works each color is precise in its consistency and delineated application. The wall of silkscreen prints—an important medium for the artist beginning in the 1960s—displayed his sense of humor in wrestling with past artistic traditions, from his renderings of scenes of heaven and hell, to the naive tropical paintings of Henri Rousseau. His impulse to render everything in rainbows even encompassed his own homage to Gustave Courbet’s infamously libertine 1866 canvas, Origin of the World (1988), to the daily household objects affixed to the surface of Study for 8:15 AM (1988), shown side by side in “Hong Hong Hong.” Dominating the center of the gallery was Long Long Rainbow Painting (1967), more than 10 meters in length, which stretched from the floor to the ceiling. It recalled one of Ay-O’s most famous later works, the 300 Meter Rainbow Eiffel Tower Project (1987), for which he suspended a rainbow ribbon from the ground to the top of Paris’s iconic structure.

While “Hong Hong Hong” presented a wide range of forms and materials that Ay-O covered in rainbows, it was difficult to ascertain from the exhibition what the rainbow meant to Ay-O beyond being a universal motif. Visitors could see across many works how the colors he chose were not always the same or consistent in number, nor do they correspond to the gradations of a natural-occurring rainbow. He would often paint in bands of color ranging in multiples of six—unlike the classical color spectrum of ROYGBIV, which has seven colors. His colors are generally opaque, saturated, often with a heavier emphasis on shades of red and yellow. In that way, Ay-O’s versions of the rainbow are conceptual representations of the visible light spectrum.

Over time, he developed many reasons for painting the rainbow. In 1964, he said, he wanted to stop using lines to describe the world because they were conceived by a “Greek philosopher.” Later he would say that he had jettisoned line and shape because they were cultural abstractions and focused on color because it was the “raw sensation of a newborn.” Painting these stripes over and over became what he would call a meditation through which he “experience[d] the vastness of the universe through color, and only then do I truly gain freedom.” Though he said that he aspired to represent a sixth sense that was transcendent—something beyond sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell—the rainbow also was instantly recognizable and symbolic.

The exhibition embodies the paradox of the “universal spirit” of the rainbow: it became such a signature motif of Ay-O’s that its visual predominance also eclipses its meanings and origins. Once Ay-O was the “rainbow artist,” rainbow art was what he did, for more than five decades since the mid-1960s. The person whose adopted artist name means “cloud vomit” would come to call his iconic style his own “rainbow hell.” Yet, it was the culmination of his two early impulses as an artist: toward a new, modern democratic art accessible to people everywhere, as well as his Fluxus-era interest in playfully exploring “concepts” such as the five senses. In the systematic painting of colors, he found his artistic freedom “to no longer paint a picture,” and through them elicited others’ joy in a popular symbolism of a natural phenomenon considered beautiful and rare.

While “Hong Hong Hong” offered excerpts from Ay-O’s formative origins and then manifold examples of his creative exuberance, there was also a creeping sense that all this light and color also covers up so much darkness. Like the self-obliteration that Yayoi Kusama found in her Infinity Nets and polka dots, Ay-O immersed himself and viewers in psychedelic progressions of richly saturated colors. A painting of his in “Hong Hong Hong” stood out in this respect: The Heart of Prajna Paramita Sutra (1981), an abstract drip-painting of repeated, multicolored acrylic tracings of Chinese characters. The sutra’s text contains the famous lines, “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form.” In other words, a rainbow.