Shows

“Posers II” at Pékin Fine Arts

In “Posers II,” the second iteration of a thematic group exhibition at the Hong Kong gallery of Pékin Fine Arts, portraiture and figurative artworks by eight artists were corralled inside the exhibition space. Venturing beyond surface-level aesthetic, the aim of the exhibition was to reveal how contemporary physiognomy manifests in artworks, with media ranging from paintings and sculptures to 3D photography. The exhibition strove to illuminate not only the stories behind the featured faces, but also relayed subtle messages from the artists.

Near the entrance of the gallery was an anaglyph, #68. Miss KIM + Miss YANG, Meari Shooting Range (2014). The work depicts two women in green military uniforms, smiling pleasantly and holding a gun. When viewed from afar, the figures appeared to be floating in a deconstructed space. However, with the aid of red-cyan glasses, the image becomes three-dimensional. The work is from Slovenian artist Matjaž Tančič’s “3DPRK” series (2014), which is a record of the people he met on a trip to North Korea. The moment of transformation from a blurred image into a sharply focused scene mirrors how the artist’s rare documentation sheds light on the lives of residents in the Hermit Kingdom. However, Tančič offers an instinctive take: “The more you think you know, the less you do.” The lifelike image that we see is merely an illusion, much like the heavily manipulated facade of the totalitarian state that is presented to visitors, including Tančič.

Other works in the show dissected authoritarianism from additional angles. For instance, a sculpture of a Chinese migrant worker stood in the center of the exhibition space; his hands clutch a lowered head in a posture that suggests frustration, while four doves flock toward him, with one landing on each arm, a third at his nape, and the fourth strafing against his torso. This is Zhang Dali’s Square No. 2 (2014). Though doves typically symbolize peace, they are aggressors in the artist’s work, pecking the worker and invading his personal space. For his “Square” series, the artist had created hyper-realistic moldings of workers’ faces with a fiberglass solution, then dropped their visages onto bodies in situations of his own design. In this sense, they are not “accurate” representations of the workers, but a reflection of Zhang’s thoughts. Under socioeconomic pressure to be “harmonious,” an ideology introduced by former Chinese president Hu Jintao that persists today, muzzling free speech for the sake of conformity stifled many in the People’s Republic. The sensations of entrapment and suppression are common themes in Zhang Dali’s oeuvre; we see this in Brownian Motion – 2 (2012), a ghoulish sculpture of a human body trapped and impaled within an arrangement of metal pipes.

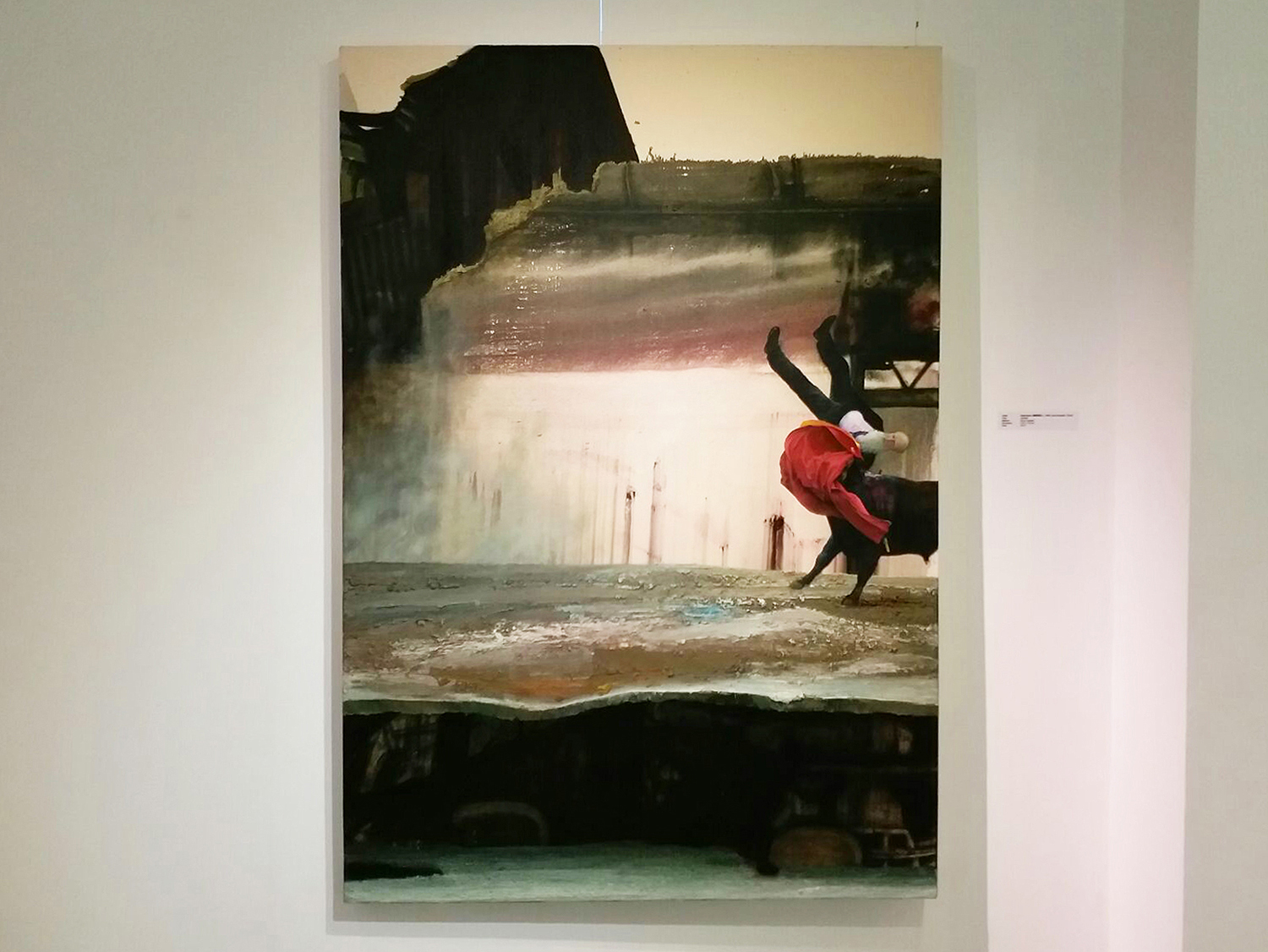

Works by other artists in the show were selected for other discursive purposes. To the left of Zhang’s Square No. 2 (2014) were two paintings by Inner Mongolia-born Nashun Nashunbatu. Untitled (2010) portrays a traditional bullfight, at the moment when the bull lunges at the matador. However, the man’s attire is not the traditional traje de luces, or “suit of lights,” that is typically associated with the bloodsport. Though he wields a muleta, the man dons a black business suit. The artist’s choice of his subject’s vestments portrays an explicit strain between old and new. Mirrored by the pictorial clash of the man and bull in the painting, two vastly contrasting worlds of tradition and modernity collide with each other. Such tensions are often found in modern society, like debates of conservation versus urban development.

This relationship between man and nature was further explored in Nashunbatu’s second painting on view. In Untitled (2006), a human figure wears a surgical mask and sunglasses, lying still on the ground. A wolf stands on him, with nails driven through its paws and into the human’s body. In the foreground, a hoopoe rests on sidewalk railing, not far from a lamp post. Behind all of this is abstractly painted wilderness, which is in striking contrast with the manmade, urban objects. Despite a tense relationship, the fates of humankind and nature are intertwined—the artist nails them together, sharing pain. The use of muted colour in both paintings also suggests despair, which reflects the artist’s pessimism toward the strain between old and new, or between humans and the rest of the world.

While the word “poser” could refer to a person who poses for a portrait, it could also mean a perplexing problem or question. In this exhibition, each artist proffered personal observations of the world, bringing forth social, political and existential issues for viewers to ponder, in turn, hopefully, sparking new ideas within the viewer.

“Posers II” is on view at Pékin Fine Arts, Hong Kong, until June 3, 2017.