Shows

Park Seo-Bo, Lee Bae, Jin Meyerson: “Origin, Emergence, Return”

Park Seo-Bo, Lee Bae, Jin Meyerson

“Origin, Emergence, Return”

Rockefeller Center

New York

Earlier this summer, while installing Lee Bae’s 6.4-meter-high sculpture in midtown Manhattan, architect Markus Dochantschi noticed a strange odor drifting down Fifth Avenue and gathering around Lee’s enormous stacks of charcoal. Lee is the first Korean artist to present work in the Channel Gardens and the timing of his installation, prophetically titled Issu du feu (2023) (“from the fire”), coincided with the thick cloud of smoke from the Canadian wildfires that were engulfing New York City. Towering in the apocalyptic orange haze, Lee’s burnt and bound bundles of pine felt part beacon, part omen.

Descending into nearby Rockefeller Center and crossing the threshold into the gallery below revealed an unusual, unfolding experience that was “Origin, Emergence, Return,” a joint exhibition featuring Lee alongside two equally prominent Korean artists: Jin Meyerson and Park Seo-Bo. Organized by Johyun Gallery and Tishman Speyer, the title points to the artists’ temporal and spatial relationship to their motherland. For these three, the separation and subsequent repatriation has been a powerful assertion of the self, their artistic voices, and their reinvention.

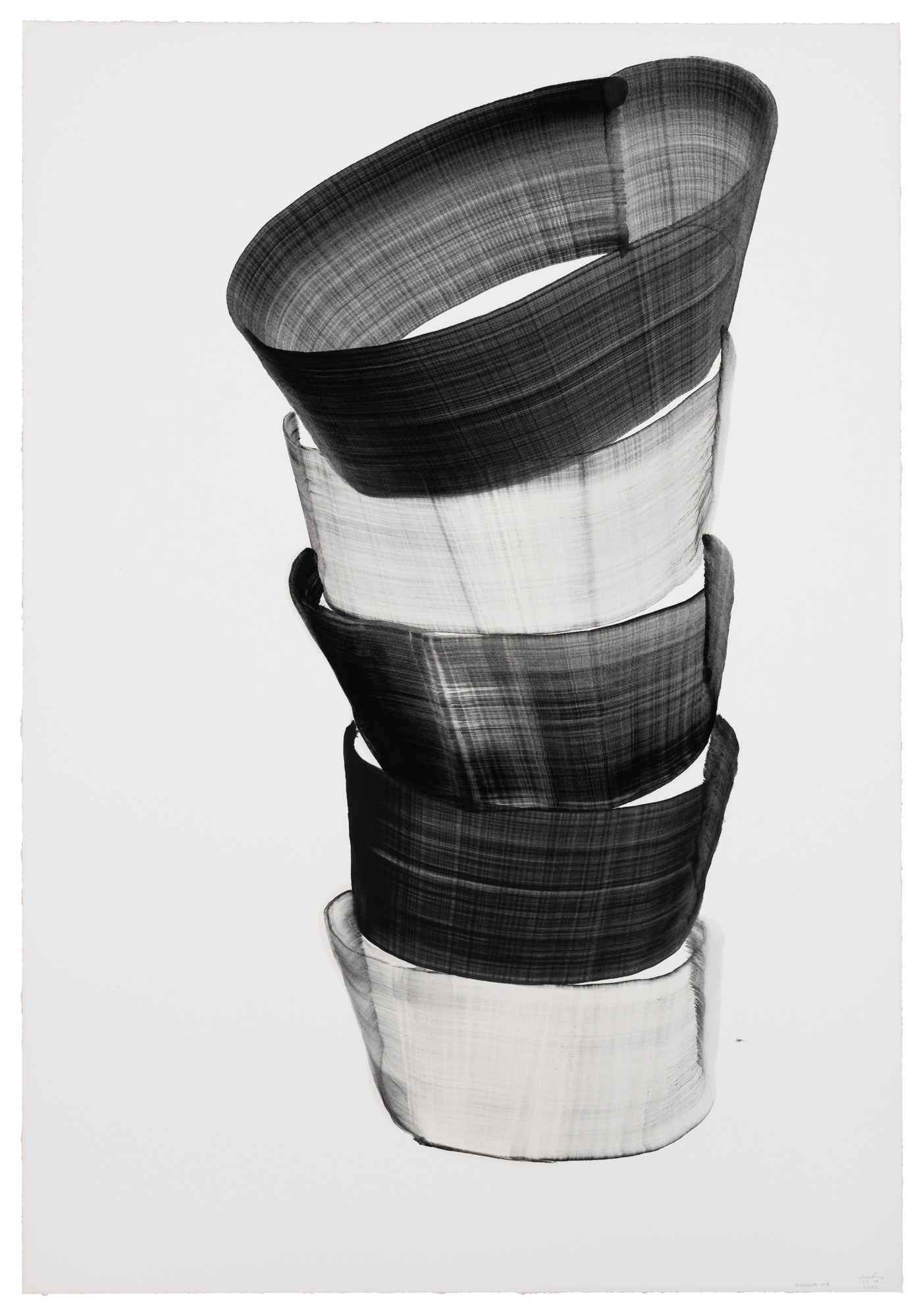

Lee’s series Brushstoke (2019–23) is misleadingly spare, as well as dignified. In a modern application of chi yun sheng tung, the traditional Chinese ink technique, these charcoal paintings exude a certain life-force. The son of a farmer, Lee pulls from shamanistic rituals that populated his upbringing in the Korean countryside; in the vein of Korean shamanism, emerging from the fire, the aberrations in his charcoal deposit a future-telling. His craft begins well before he marks the canvas or conceives of a sculpture and his placement of the wood in the kiln is an art form unto itself that results in a variety of tones and textures. Even the type of wood he selects holds great meaning—pine, primarily, for the sporadic cracks that appear in the firing process, and its ability to retain, at least a forgiving semblance of, its original form. Poetically, pinewood has a lifespan of 100 years; as charcoal, that extends to 1,000.

The transformational and destructive power of fire was a recurring motif here, and for Jin Meyerson, the youngest of the three artists, it is existential as well as intimate. The turbulent painting POST CALIFORNIA (2021) echoes what befell the city in June. The surging, molten galaxy of paint contains visual residue of the Caldor Fire, a devastating wildfire that burned 221,835 acres in California and a frightening byproduct of the climate crisis. Fire also speaks to what is most central to Meyerson’s practice: the erasure of his own personal history. Adopted from Korea by an American family, Meyerson returned to the orphanage—the site of his earliest memories in Korea—to look for his records, but was told the building and everything about his past had burned down. He has neither a birth certificate nor any way to trace his biological family.

Akin to his story, his art is an emancipation of the past, where even his source material, scrambled by computer-generated imagery and randomization software, is undecipherable. The result is vertiginous samplings in gorgeous paint. Perhaps a daring and rare example of what it looks like to break the algorithm, there are ever-increasing meta layers to Meyerson’s work. A hint of his eldest daughter is evident in SEANCE 4.1 (2022): an iridescent and unrecognizable figure with a sheet over her head, glowing from a light source underneath. If the viewer looks closely, that same textured sheet is rendered around the gallery room, nearly obsolete.

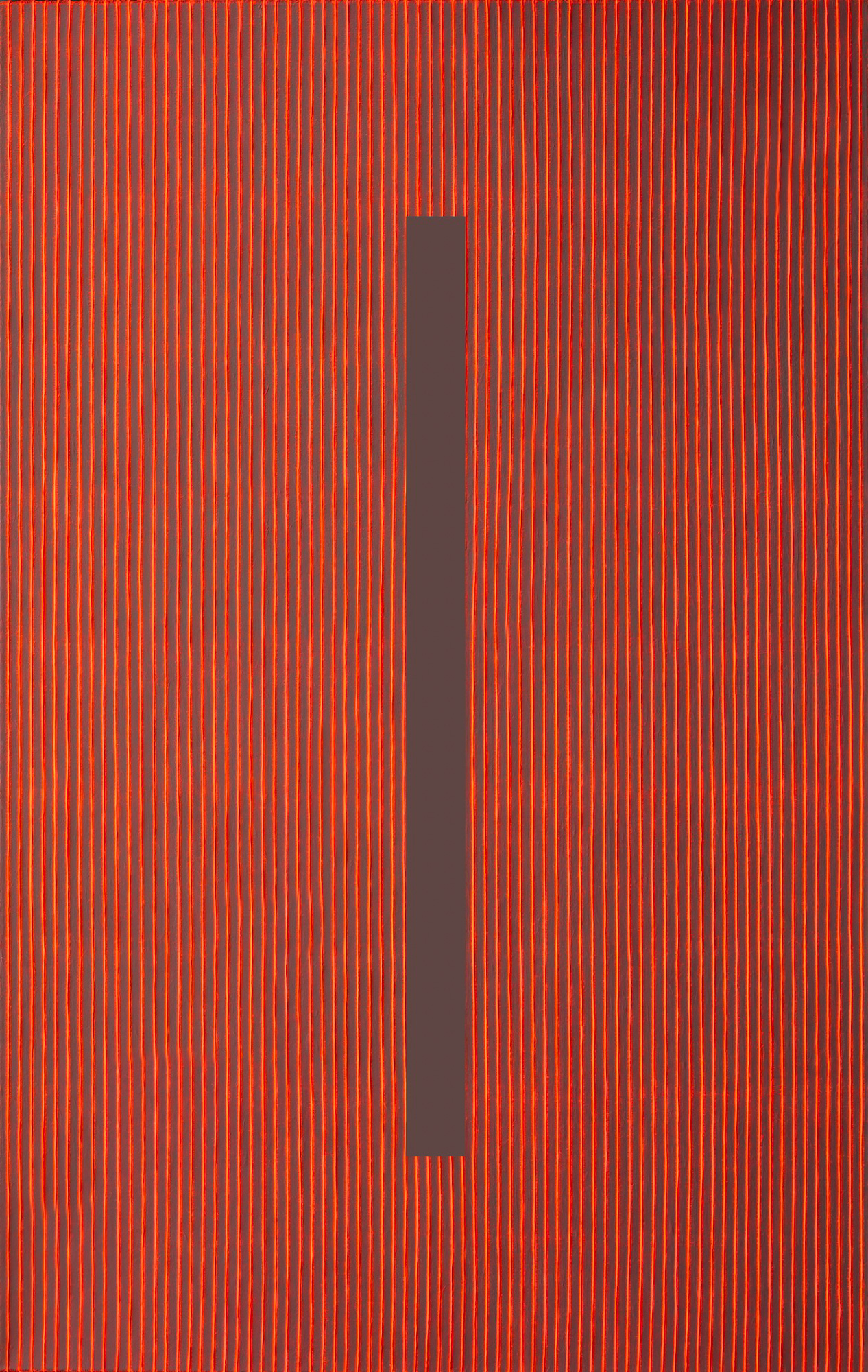

Where Meyerson’s paintings exhale, Park Seo-Bo’s work inhales. On opening night, during the artist talk and in the dimmed light, Park’s three central monochrome paintings from his longrunning Écriture series (2006) glowed like red-orange embers. Inspired by light and foliage, their aura has immense depth, which Park compares to the six-year fermentation process of mugeunji (aged kimchi). In comparison with Lee and Meyerson, the ashes that the 91-year-old Park creates from are less recent and more conceptual: a reemergence of a nation from the fire of colonialism and war. Heralded as the founder of Dansaekhwa, his famous monochrome style has less to do with color and more to do with an emptying on canvas through repetition, and thus healing. In Ecriture No. 061224 (2006) the slender threads of color and paint that frame a beam of negative space carry a magnetism. Like blotting paper, the breadth of his 40 paintings absorbs and receives their surroundings, surrogates for meditation as viewers enter their presence.

Aesthetically the artists differ in style and media, but there was a concrete through-line in the triangulation: “Origin, Emergence, Return” emanates with notable, psychic, and restorative works of postwar Korea. The exhibition statement delineates Park as “Origin,” Lee as “Emergence,” and Meyerson as “Return.” Yet in the immaterial void between the works the viewer can begin to decipher that the conversation is less compartmentalized. All three trace this life cycle, unleashing potential and sentience. As Jin Meyerson once revealed: “I realized that there are no coincidences, only sequences.”

Paige Haran is a writer and curator based in Mexico City. She has developed exhibitions and programs around the world in collaboration with Art Dubai, The Getty, de Young Museum, Frieze, Google, and World Bank Group, among others.