Shows

“Noguchi for Danh Vō: Counterpoint” at M+ Pavilion

In musical theory, “counterpoint” describes the interaction of two or more independent melodies. This was the conceptual basis of “Noguchi for Danh Vō: Counterpoint,” an exhibition conceived by Danish-Vietnamese contemporary artist Danh Vō, featuring a selection of his works alongside a mini-retrospective of seminal Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi. Presented at the M+ Pavilion in Hong Kong in collaboration with New York’s Noguchi Museum, “Counterpoint” promised a “unique dialogue” between the two artists, who have each sought to redefine what constitutes art.

The Pavilion’s main space was largely devoted to an elegant display of Noguchi’s eclectic works, spanning nearly five decades. Installed just outside the entrance, Noguchi’s sculpture Cloud Mountain (1982–83) was an apt introduction to his varied style, which was oriented toward erasing the boundaries between cultures, disciplines, and art forms. Evoking the layered mountains of shanshui painting via intersecting galvanized-steel plates, Cloud Mountain combines modernist and classical Chinese aesthetics with industrial material. Within the Pavilion, the open-plan layout further established equality between Noguchi’s functional and fine-art pieces. Radio Nurse (1937), an early design for a radio case, resembling both the heart-shaped face of a wimple-wearing nurse and a kendo mask, illustrates the artist’s quiet ingenuity and hybridized style. Further into the exhibition space were Bamboo Basket Chair (1950/2010), a piece of modernist furniture elevated to fine-art object on a circular wooden base, and Akari 21N (1968), Noguchi’s iconic paper lantern that electrified traditional Japanese craft.

Noguchi’s fondness for innovative aesthetics coexisted with an idealistic belief in art’s capacity to counter societal tragedy with unassuming beauty. This was seen in his poetic sculptures made shortly after World War II, such as the collapsible, brushed-bronze Strange Bird (1945/71), redolent of alienation and disfigurement; and the suspended Bird’s Nest (1947), of glued wooden sticks and abstract, wing-like pieces, suggesting tiny birds balancing precariously on inosculated twigs.

The show’s centerpiece was Vō’s Untitled (Structure for Akari PL2) (2018), a life-sized Chinese pavilion, with Noguchi’s geometric light sculptures hanging on two sides. Constructed using the ancient Chinese mortise-and-tenon technique, Untitled embodies the modularity and functionality seen in many of Noguchi’s modernist pieces, and complements the latter’s use of traditional Asian craft and aesthetics. Unfortunately, the exhibition design did not serve the rest of Vō’s works particularly well. Affixed to the wall less than a meter away from one of the pagoda’s lamps was January 2015 (2015), a framed silk painting by Chinese painter Li Peng, based on a work by an unknown Vietnamese artist depicting the dismemberment of a French Christian missionary—though one could barely make this out due to the glare from the lamps, prompting one to ask why it was included at all.

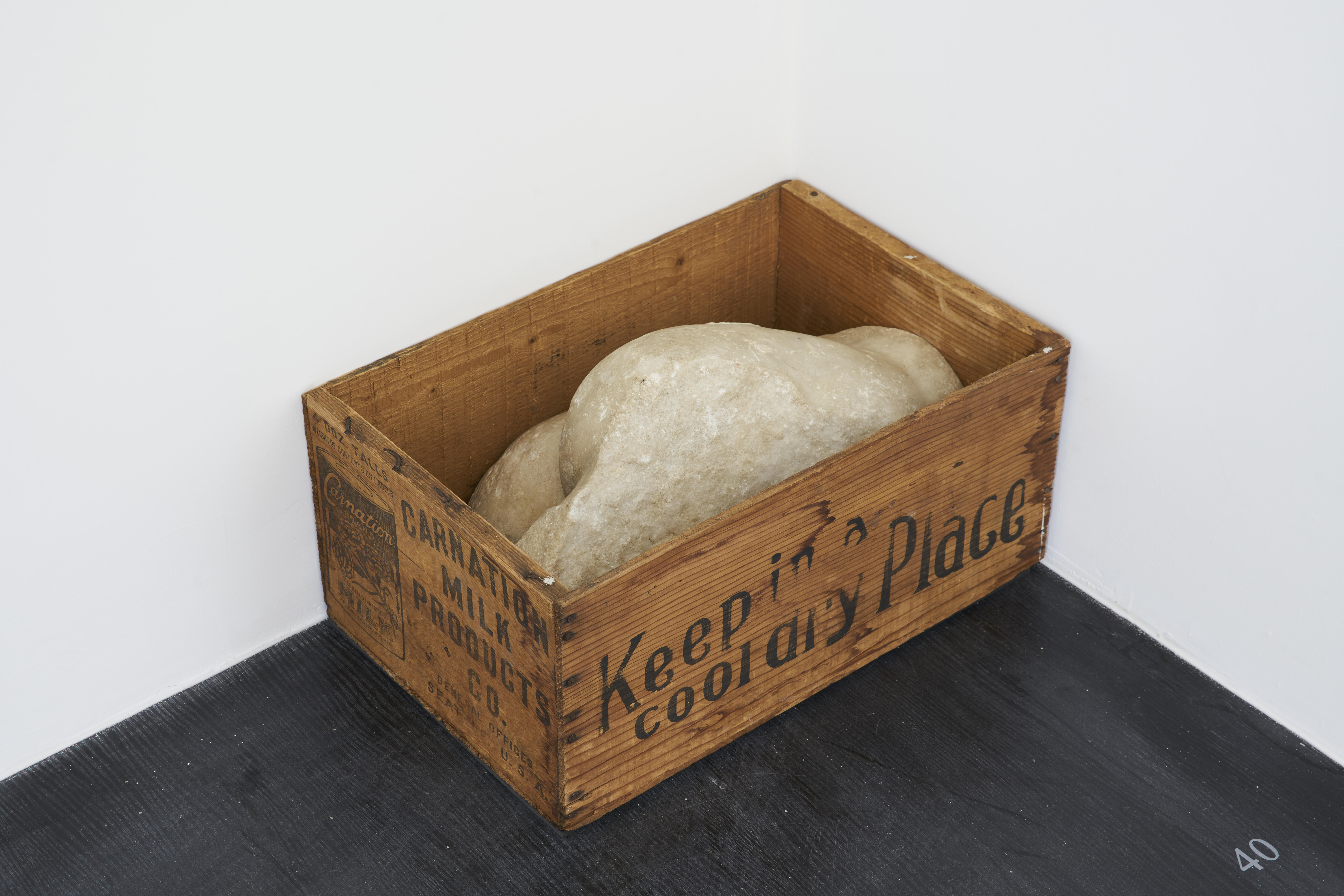

Further opportunities for dialogue between the artists were stymied by Vō’s decision to house the bulk of his contributions in shipping containers outside the main exhibition space. Arguably, the power of his work lies in his clever deployment of juxtaposition, which, besides mashing together incongruous artifacts, sees the artist highlighting the extraordinary consequence of ordinary objects (say, pen tips used to sign a treaty enabling foreign military aggression). Placed within the vaunted halls of a museum, Vō’s ydob eht ni mraw si ti (2015)—a wooden crate holding a marble body part from a sculpted Greek athlete—has a playful insouciance, with its dismembered Adonis, and a backwards title (the devil is believed to speak in reverse) that references the film The Exorcist (1973). This is lost when it is installed in the corner of a small container, which carries no connotations of reverence.

For an exhibition built around the notion of dialogue, there were few points of meaningful interaction, and the spatial disjuncture was enough for possible connections to go from subtle to tenuous. The central concept of independent melodies that occasionally overlap thus comes across as far too easy an organizing principle, while the groups of the two artists’ works had little else, curatorially, that allowed them to stand on their own as separate, compelling displays. Barring rare moments of harmony, the two artistic strands in “Counterpoint” were too often feebly held together by the third tune of curatorial imposition.

Ophelia Lai is ArtAsiaPacific’s reviews editor.

“Noguchi for Danh Vō: Counterpoint” is on view at M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong, until April 22, 2019.