Shows

Nadim Karam’s “Urban Stories”

At first glance, the simplified forms and exaggerated lines of Lebanese artist Nadim Karam’s sculptures recall those of European Primitivism. Unlike many works from that movement, however, they explore and reflect the contours and richness of their temporal and geographical settings, just as the arrangement of the fine patterns in Karam’s sculptures are informed by their outlines.

“Urban Stories,” the artist’s first show at The Fine Art Society in London, was a survey of his multidisciplinary practice in sculpture and painting over the past 20 years, during which he has become best known for his often-unsolicited public art projects. Karim was born in Senegal, raised in Lebanon, and continued his studies in architecture in Japan, where he remained to teach afterwards. He first conceived The Archaic Procession (1997–2000)—his most famous body of work—while in Tokyo. It consists of 1,001 theriomorphic signs—an oblique reference to the tales of Scheherazade in One Thousand and One Nights—that the artist developed into sculptures, or rather “urban toys,” and introduced into Prague and Beirut.

On the gallery’s first floor was a wall dedicated to pages from Sketchbook 58 (1993), in which Karam developed much of The Archaic Procession. These watercolors scanned on the wall like unintelligible scenes from a rediscovered cave painting, where archetypal forms lined up in silhouetted profile to play out some long forgotten myth. On closer inspection of the images, however, their zoic shadows are not situated in natural environments but ambiguous cityscapes, foretelling their sculptural manifestation in Beirut.

The Archaic Procession did not find its way only to the city. Descendants of its animalistic archetypes have since become pleasantly decorative polished steel sculptures, released in editions. There was a sense of spontaneity to the animal pieces Karam once let loose in Beirut, like escapees from a zoo; every few months, he would change their positions at night to surprise the city’s inhabitants. To see these derivations produced in sets and placed on mantelpieces as with Wild Cat (2011), Miu (2017) and others, clashes with this history. Whereas these forms were meant to celebrate and sustain the stories and auras of cities, here they appeared sterile and tamed. Sculptures from the “Cultural Warrior” series, however, develop Karam’s forms more effectively. In pieces such as Baby Phoenician on a Camel, Hannibal on an Elephant, and even the generic Diva on a Rhino (all 2013), stainless steel figures atop corten steel animals conjure an engaging historicity akin to his early watercolors.

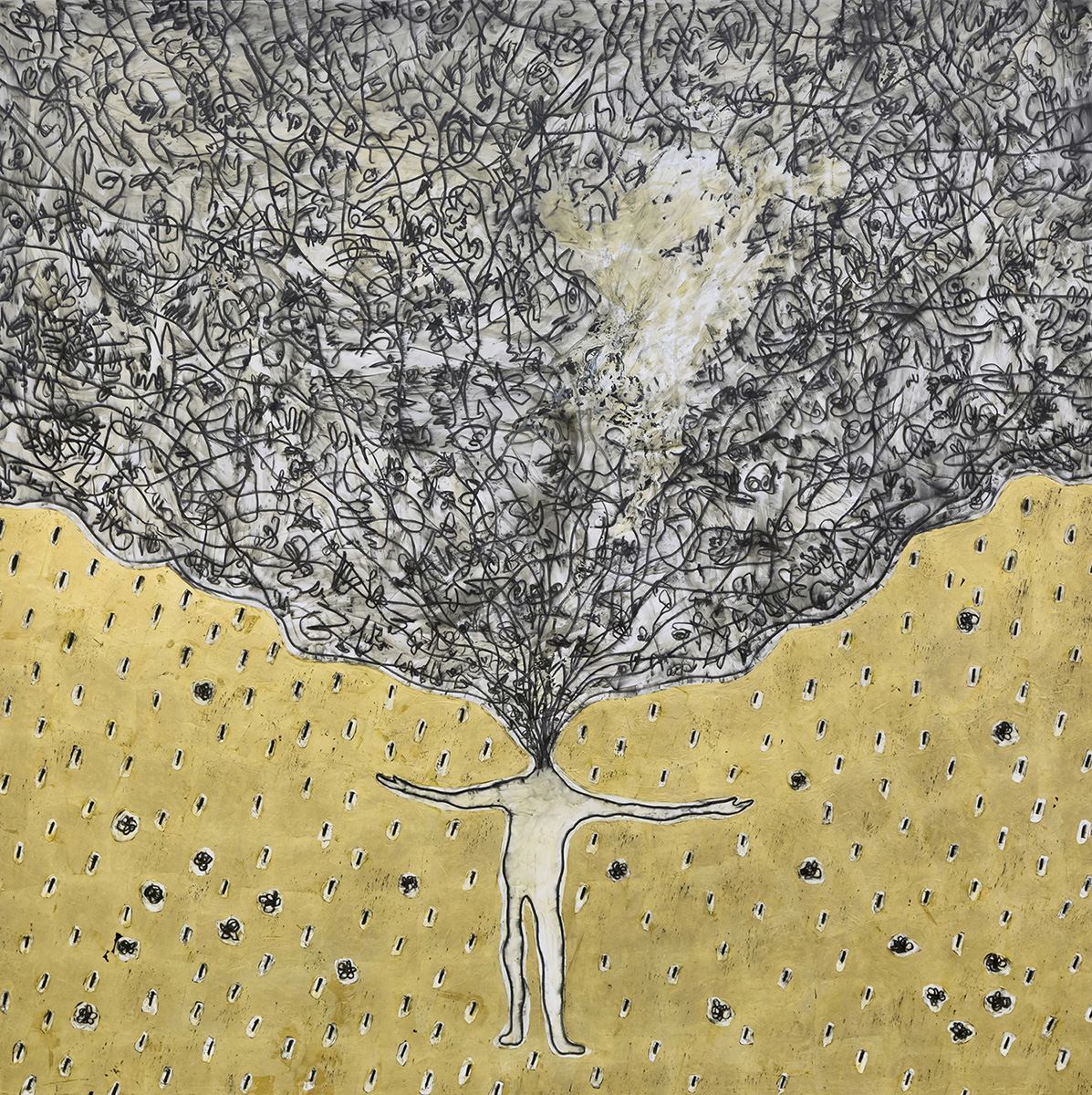

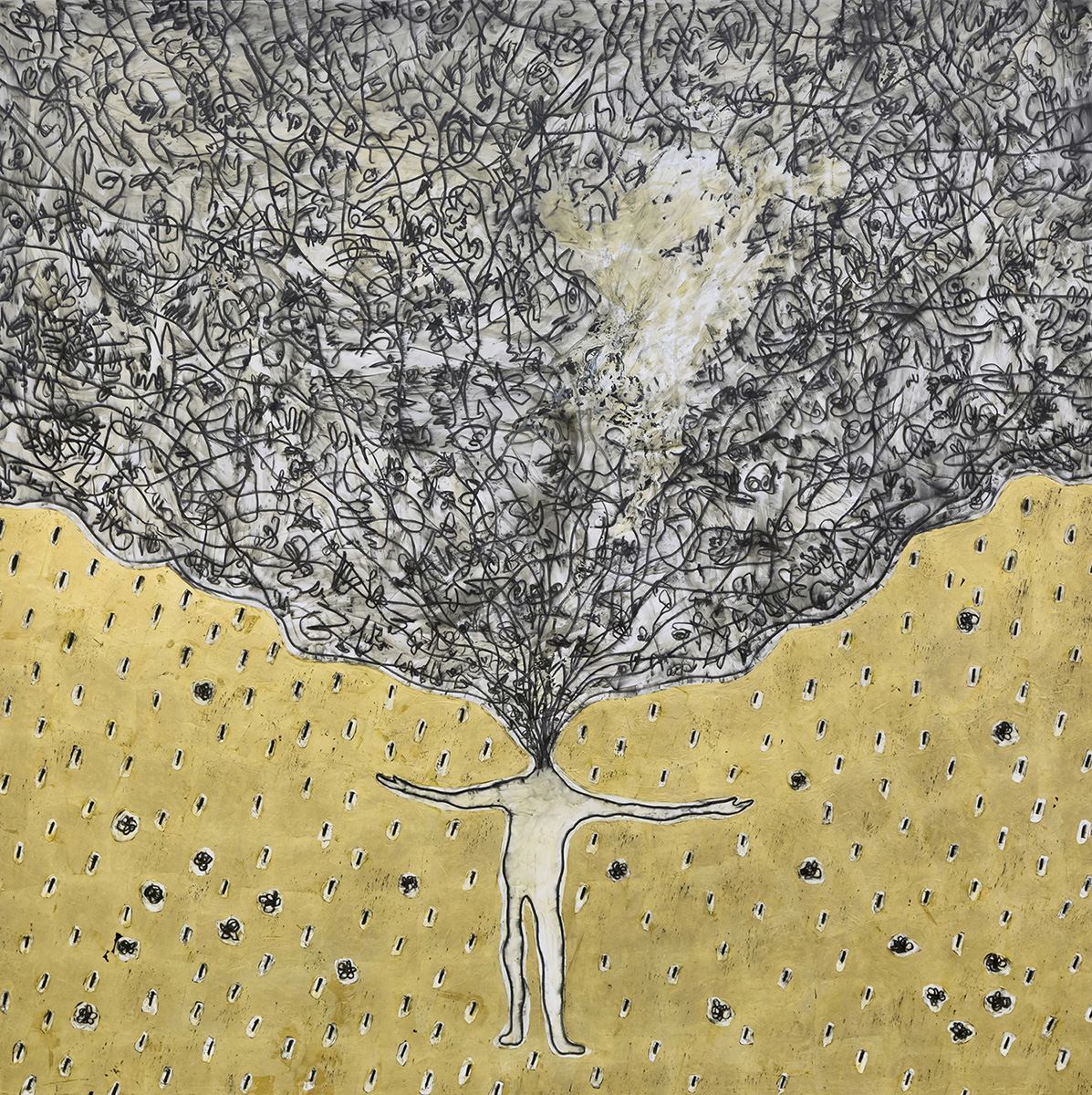

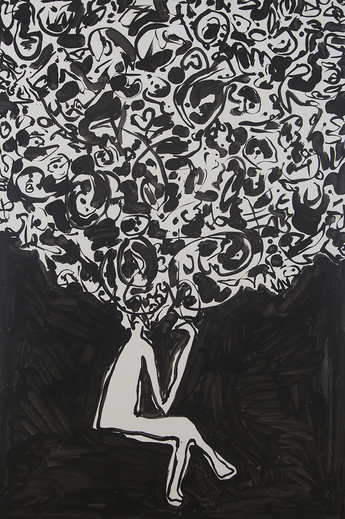

In recent years, Karam has also worked outside of the language he developed for The Archaic Procession, creating sculptures and paintings of headless human figures with wide plumes of smoke rising from their necks. The imagery in paintings such as Raining Thoughts (2015) is obvious but compelling: a playfully delineated figure stands, arms open, against a gold background, scribbled animal forms tangled in the cloud emitted from his neck. The smoke motif is notably refined elsewhere in another painting, Growing Thoughts (2016), and a steel sculpture, Stretching Thoughts, Seated (2015), both of which resemble Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker (1884–1916)—at least up to the neck.

Pieces from the “Stretching Thoughts” series (2013–16) represent an early step toward abstraction for Karam that is most fully represented in Trou de Mémoire, Memory and Trou de Mémoire, Void (both 2017), a pair of polished stainless steel sculptures where two large, reflective discs stand facing each other on stubby legs. On one disc are incised hundreds of details from the vocabulary of Karam’s career as an artist; the other is pristine. In the center of each is a hollow around which both the steel and the fidelity of its reflection are warped. Despite the unquestionable beauty of the sculpture’s detail, material, and craftsmanship, it is conceptually lacking. The blank disc ostensibly represents a void in the face of memory—the so-called trou de mémoire—and yet reflects the viewer, as well the installation’s somewhat cluttered surroundings.

Neither Karam’s many talents, fascinating career, and impressive body of multidisciplinary work were in question here. Nor was the plushness of The Fine Art Society gallery—whose ground and first floors eschew the white cube aesthetic—problematic in itself. In combination, though, Karam’s forms became toys for the home where once they were playthings for cities; they assumed the stature of bibelots where once they were timeless giants.

Nadim Karam’s “Urban Stories” is on view at The Fine Art Society, London, until May 19, 2017.