Shows

Mobile M+: Yau Ma Tei

“Mobile M+: Yau Ma Tei” is the second in a series of “nomadic” exhibitions organized by the M+ museum, whose building will be completed in 2017. Seeking to generate collaboration and dialogue between local artists and the public, M+ selected seven Hong Kong-based artists—Kwan Sheung-chi and Wong Wai-yin, Leung Mee-ping, Erkka Nissinen, Pak Sheung-chuen, Tsang Kin-wah and Yu Lik-wai—to create installations along Portland and Shanghai streets in the heart of Yau Ma Tei, the Kowloon neighborhood where the future M+ Museum will be. The artists’ projects explored issues especially related to the lives of their fellow Hong Kong citizens, as well as the city and its history.

In a small park on Man Ming Lane and Portland Street, Leung Mee-ping’s “I Miss Fanta,” four weatherworn and long-ignored neon signs of Coca-cola and Sprite advertisements, lie stacked on top of one another. Across the street, hidden among items in a recycle and repair shop, photos of Macau’s iconic Avenida de Almeida Ribeiro—where the signs used to hang—are displayed alongside a video showing the signs being transported from the Coca-Cola factory in Macau to the park in Yau Ma Tei. The installation’s title tells the story of the signs’ separation from the Fanta advertisement they used to hang beside, an anthropomorphized evocation of longing for a life that once was. Initially, Leung hoped to re-mount the old signs on buildings in Yau Ma Tei, allowing them to relive their past lives, once again radiating their commercial glow. However, due to prohibitive regulations, the signs were instead arranged prostrate on a grassy patch of ground in the park, highlighting their dilapidated state– their quickly accumulated history set against the slowly gentrifying neighborhood, perhaps an indication that the past cannot, in fact, be recreated.

Up Portland Street, Kwan Sheung-chi and Wong Wai-yin housed their interactive piece, “To Defend the Core Values is the Core of the Core Values,” for which, in a competition for a solid gold coin embossed with the phrase “Hong Kong’s Core Values,” they asked Hong Kong citizens to scrawl answers in response to the question, “Your core values of Hong Kong are?” The chosen submission, “Long Hair,” the nickname of Leung Kwok-hung, founding member of the League of Social Democrats, never claimed an author, so the artists invited Leung himself on a boat ride in Victoria Harbor, where he could decide whether to keep or toss the coin. Despite the “apolitical” stereotype of Hong Kong people, the recent election of the chief executive—a notoriously unequal process whereby an election committee of fewer than 2,000 have the right to cast votes that represent over seven million Hong Kong citizens—aroused widespread discontent and a desire by citizens to have their voices heard. Kwan and Wong’s piece appealed to this desire, if only in a minor and perhaps superficial manner. In a video documenting Leung’s decision to keep the coin, he bemoans the lack of autonomy in Hong Kong’s culture and politics, citing the dominant power of a “Cash is King” mentality, and long years of political oppression, as reasons why Hong Kong lacks a true and original value standard. Leung, it seems, questions the very nostalgia that Leung Mee-ping’s piece celebrates.

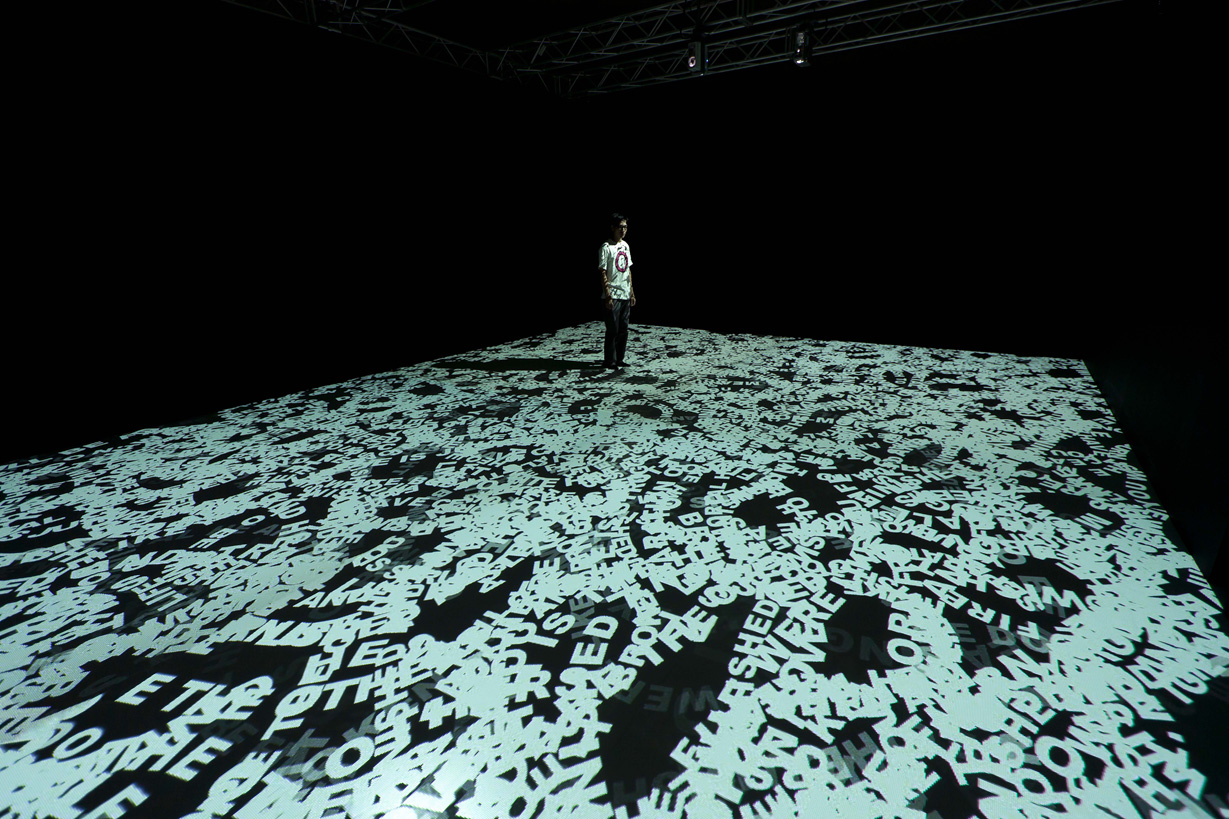

Tsang Kin-wah’s installation The Fourth Seal–His Is to No Purpose and He Wants to Die for the Second Time, the latest installment in his “Seven Seals” project (2009– ), draws its inspiration from the story of the fourth horseman of the apocalypse, described in the Book of Revelations. Inside a dark pop-up tent on the corner of Shanghai Street, projected words and phrases derived from Tsang’s personal musings on the Bible, politics and society, appear to slither across the floor, bearing portents of death. Emerging slowly at first, they pick up in speed and density until the room is consumed in the bright projected light of the repeated sentences—which then fade and repeat the process again. Tsang invites the viewer to contemplate the grander moral implications of personal dissatisfaction prompted by these rapidly changing times.

While this was certainly art in the public sphere, as installations were marked merely by a single striped cone or postcard sized poster, most locations were inconspicuous to the point that even determined searching sometimes proved futile. Pak Sheung Chuen’s “L” project, for example, was a series of “artistic gestures” derived from everyday observations jotted into his notebook that revealed artistic moments in everyday life. The project embodied M+’s mission statement, but lacking a fixed space, Pak’s works were the most difficult to experience firsthand. Pak’s project included courses on creative interaction taught by the artist, film screenings, social experiments and initiatives, and other activities held across Yau Ma Tei and nearby Mong Kok, to which Pak invited the public via social media. In “Alternative Ways of Reading,” Pak led groups of 10 participants in finding new ways of engaging with books, with simple directions such as: “compose a short article with the [Chinese] characters at the 4 corners of each page,” or “look for the 6th character on page 66 of 6 books that together form a sentence,” for example. In “June 4th Camp Fire” Pak set out to “Convert the entire memento for June 4th [Tiananmen Square Massacre] to the belief of worshipping brightness. / Snip out all the Chinese character “fire” as seen on newspapers and burn them with fire. / Write out “June 4th” on light switches. You mourn every time you switch off the lights.”

Overall, the artworks in “Mobile M+: Yau Ma Tei” invited audiences to take a wandering journey. As a visitor to this city, constantly lost even while clutching a map, Mobile M+ provided an exciting opportunity to explore a place I barely knew. The exhibition, however, seemed best suited not for the curious tourist, but for the jaded citizen compelled to rediscover their city and neighbors.