Shows

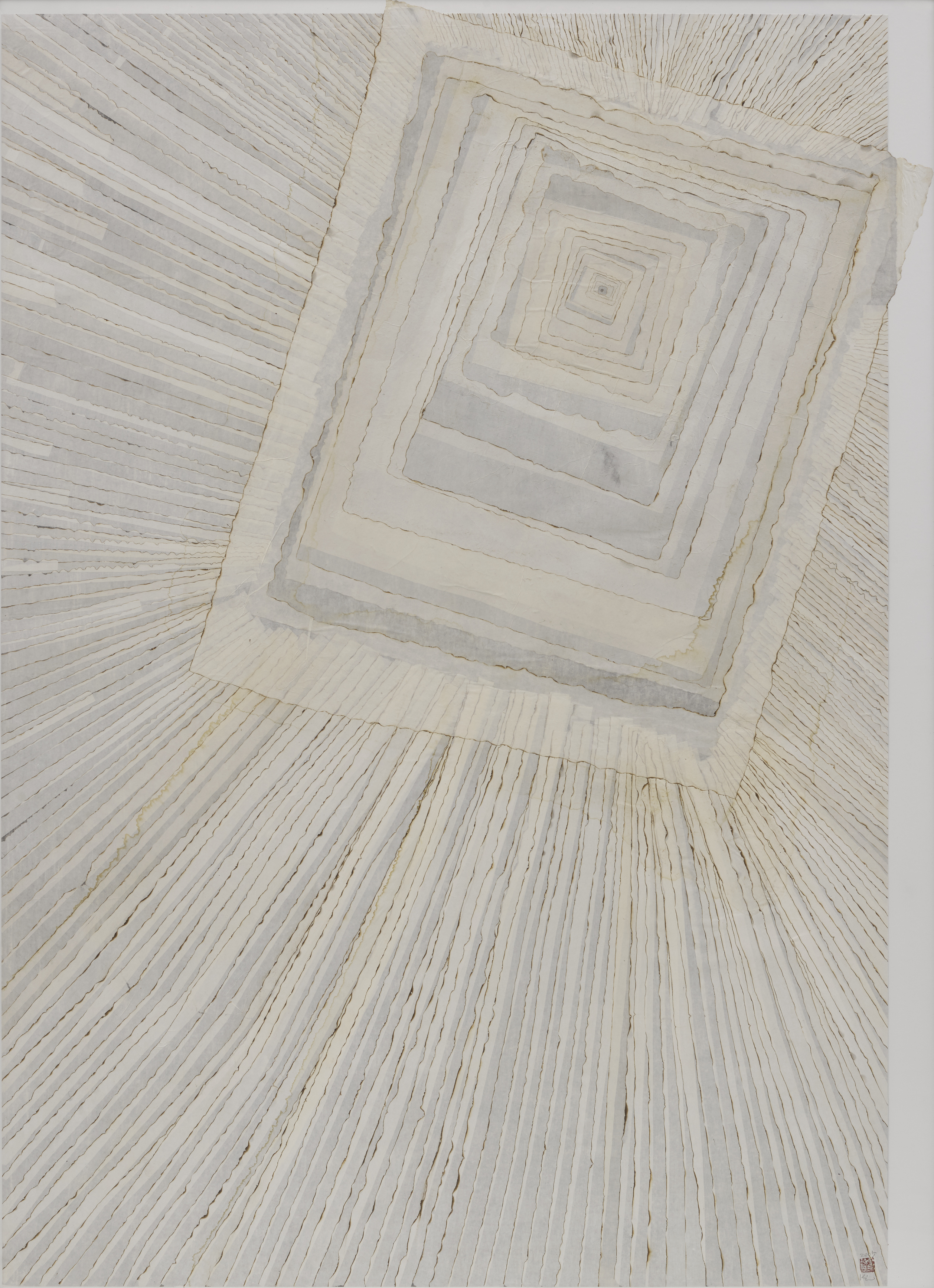

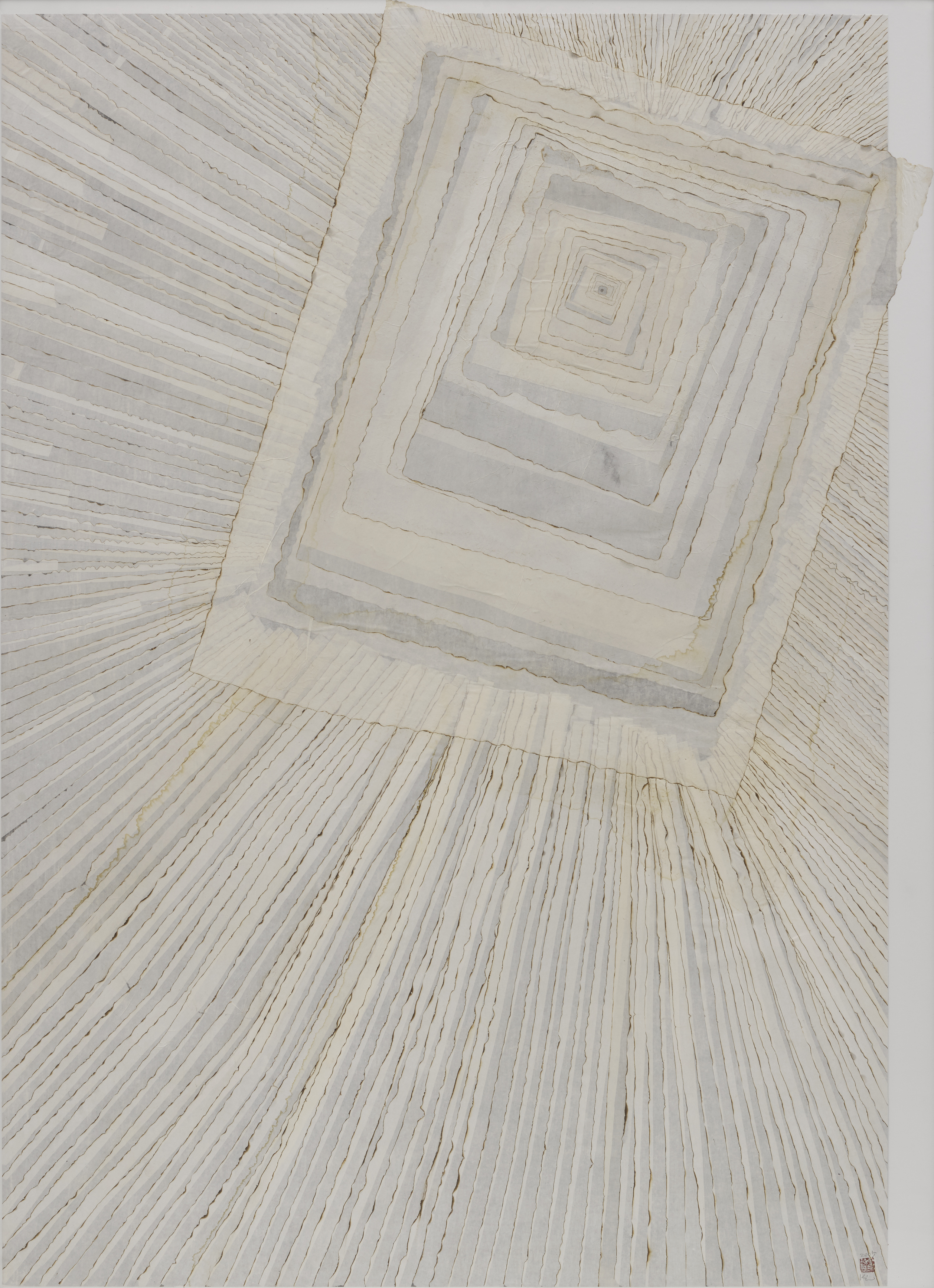

Minjung Kim’s “The Memory of Process”

Minjung Kim studied with the key proponent of the Dansaekhwa movement, Park Seo-Bo, in Seoul in the early 1980s. She subsequently became one of the few female artists associated with the male-dominated school. Born in Gwangju, Kim is now living and working between the south of France and the United States. Although she has been featured extensively in exhibitions throughout Europe and the US, Kim is less known in the United Kingdom. Her exhibition, “The Memory of Process,” presented at White Cube Mason’s Yard, was her first with the gallery. The show operated as a comprehensive survey, highlighting the strength and breadth of Kim’s explorations with serene, minimal geometries and her techniques of modularity and repetition.

Grouped together in the upstairs space was an arrangement of conceptual, mixed-media works made by Kim in the mid-2000s. These abstract canvases are made of traditional Korean hanji paper, which is processed from dried mulberry tree bark. The artist burns the edges of the paper with a very small candle or incense stick and then begins to layer them in strips with a technique akin to collage. The process is very labor intensive, allowing Kim—who describes her own work as “a visualization of Zen and Tao”—to fall into a meditative state. As in a ritual, mind and body are connected through the repeated acts of cutting, burning and gluing. Despite using mathematical rigor, the vegetal material is ultimately shaped into organic forms Kim imagines, including spirals, as in Nautilus (2010), or bamboo canes, seen in Bambu (2005). The hanji is pale, almost translucent, and only up close can the viewer see the individual nuances of each work, or the darkened edges where the fragments have been burnt. The material is thus caught in a moment of vanishing, both present and absent, with its transience preserved.

In the “Dobae” series (2015)—exhibited in the gallery’s small downstairs space—Kim changes tack with her application of the hanji. As opposed to the horizontal or vertical strips in other works, the hanji appears in rough patches, all overlapping. The scorching of the papers, creating a constellation of holes, is brought to the fore as a central feature in the composition, and the application of a stain creates a visceral effect, harmonizing the dappled, dark burn marks with the light paper. Translated from Korean, “dobae” means “wallpapering.” These works were inspired by a memory from Kim’s childhood: visiting the houses of the laborers who worked on her grandfather’s rice fields, and how they would keep the mud walls stable and insulated by layering hanji papers. References to other Korean traditions, specifically, landscape painting, are evident in the “Mountain” series (2008-11). Monochromatic washes of ink are spread in various densities in order to create a gradient, shaded effect. Despite their forms, which evoke mountains, these works were inspired by the sound of the incoming and outgoing tide when Kim was working from a studio on the Amalfi coast.

The main downstairs gallery was dedicated to Kim’s “Pieno di Vuoto” series (2008– ). The title translates from Italian to “full of emptiness,” implying how the spectator’s imagination is what enriches an artwork, imbuing shapes or colors with personal allusions or meanings. The work is not didactic, rather inviting and open to interpretation. Unlike the monochrome serenity of the other work, here, the pieces of hanji paper have been dyed in bold primary colors, and are assembled in circles. Kim was inspired to use colors when looking at all the vibrant book spines facing outward in her library, imagining them all jostling for her attention. The densities of the discs cause the eyes to fuzz and the circles spiral out and evade rationality. This specific body of canvases, bringing to mind Bridget Riley’s dizzying op art or Josef Albers’ playful juxtapositions of colors, effectively embodies Kim’s experimental convergence of Eastern artistic traditions with modes of European modernism.

Minjung Kim’s “The Process of Memory,” curated by Katharine Kostyál, is on view at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London, until March 10, 2018.